Data Wrangling

sed&grep

sed: stream editor, The s command is written on the form: s/REGEX/SUBSTITUTION/, where REGEX is the regular expression you want to search for, and SUBSTITUTION is the text you want to substitute matching text with.

grep: Find patterns in files using regular expressions and print.

less: Open a file for interactive reading, allowing scrolling and search.

| command | meaning |

|---|---|

sed 's/查找内容/替换内容/' 文件名 |

替换文件中第一个出现的字符串,并打印结果 |

sed -E 's/正则表达式/替换内容/g' 文件名 |

替换文件中所有符合正则表达式的部分 |

grep "search_pattern" path/to/file |

Search for a pattern within a file |

grep -i |

Perform case insensitive matching. By default, grep is case sensitive. |

less source_file |

Open a file |

Regular Expressions

Regular expressions are usually(though not always) surrounded by /. Most ASCII characters just carry their normal meaning, but some characters have "special"matching behavior. Exactly which characters do what vary somewhat between different implementations of regular expressions

Very common patterns are:

| character | meaning |

|---|---|

. |

means "any single character" except newline(\n) |

* |

zero or more of the preceding match |

+ |

one or more of the preceding match |

[abc] |

any one character of a,b,c |

(RX1|RX2) |

either something that matches RX1 or RX2 |

^ |

the start of the line |

$ |

the end of the line |

sed's regular expressions are somewhat weird, and will require you to put a \before most of these "special" characters to transfer their character.

* and + are, by default ,"greedy". they will match as much text as they can, and you can just suffix * or + with a ? to make them non-greedy, but sadly sed doesn't support that. we could switch to perl's command-line mode though, which does support that construct:

sed for the rest of this, because it's by far the more common tool for these kinds of jobs. sed can also do other handy things like print lines following a given match, do multiple substitutions per invocation, search for things, etc.

sed -E 's/.*Disconnected from (invalid |authenticating )?user .* [^ ]+ port [0-9]+( \[preauth\])?$//'

[^ ]+ match any non-empty sequence of non-space characters. the entire log becomes empty. We want to keep the username after all. For this, we can use "capture groups". Any text matched by a regrex surrounded by parentheses is stored in a numbered capture group. These are available in the substitution as \1,\2,\3,etc.

sed -E 's/.*Disconnected from (invalid |authenticating )?user (.*) [^ ]+ port [0-9]+( \[preauth\])?$/\2/'

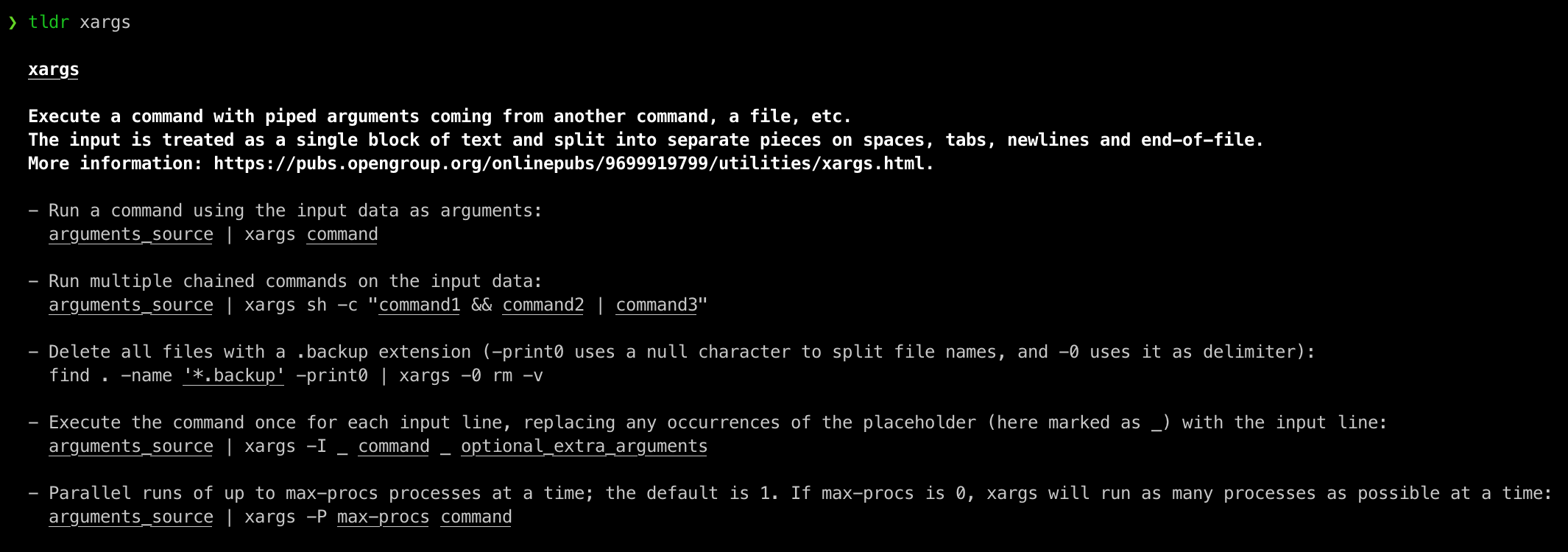

some other data wrangling commands

Regrex one

Lesson1: An Introduction, and the ABCs

the first thing to recognize when using regular expressions is that everything is essentially a character, and we are writing patterns to match a specific sequence of characters(also known as a string). Most patterns use normal ASCII, which includes letters, digits, punctuation and other symbols on your keyboard like %#$@!, but unicode characters can also be used to match any type of international text.

In fact, numbers 0-9 are also just characters and you can look at an ASCII table where they are listed sequentially. a number of special metacharacters used in regular expressions can match a specific type of character. In this case, the character \d can be used in place of any digit from 0 to 9. the preceding slash distinguished it from the simple d character and indicates that it is a metacharacter.

lesson2: The Dot.

In some card games, the joker is a wildcard and can represent any card in the deck. Similarily, there is the concept of a wildcard, which is represented by the . metacharacter, and can match any single character(letter, digit, whitespace, everything). In order to specifically match a period, you need to escape the dot by using a slash . accordingly.

lesson3: Matching specific characters

There is a method for matching specific characters using regular expressions, by defining them inside square brackets. For example, the pattern [abc] will only match a single a, b, or c letter and nothing else.

lesson4: Excluding specific characters

In some cases, we might know that there are specific characters that we don't want to match too, for example, we might only want to match phone numbers that are not from the area code 650.

To represent this, We use a similar expression that excludes specific characters using the square brackets[] and the ^(hat). for example, the pattern [^abc] will match any single character except for the letters a, b, or c.

lesson5: Character ranges

there is a shorthand for matching a character in list of sequential characters by using the dash to indicate a character range. For example, the pattern [0-6] will only match any single digit character from zero to six, and nothing else. And likewise, [^n-p] will only match any single character except for letters n to p.

Multiple character ranges can also be used in the same set of brackets, along with individual characters. An example of this is the alphanumeric \w metacharacter which is equivalent to the character range [A-Za-z0-9_] and often used to match characters in English text.

Lesson 6: Catching some zzz's

Caution

some parts of the repetition synax below isn't supported in all regular expression implementations.

We've so far learned how to specify the range of characters we want to match, but how about the number of repetition of characters that we want to match? one way that we can do this is to explicitly spell out exactly three digits.

A more convenient way is to specify how many repetition of each character we want using the curly braces notation. For example, a{3} will match the a character exactly three times. Certain regular expression engines will even allow you to specify a range for this repetition such that a{1,3} will match the a character no more than 3 times, but no less than once for example.

This quantifier can be used with any character, or special metacharacters, for example w{3}(three w), [wxy]{5}(five characters, each of which can be a, w, x, or y) and .{2,6} (any character between two and six).

lesson 7: Mr.Kleene, Mr.Kleene

A powerful concept in regular expressions is the ability to match an arbitrary number of characters. For example, imagine that you wrote a form that has a donation field that takes a numerical value in dollars. A wealthy user may drop by and want to donate $25,000, while a normal user may want to donate $25.

One way to express such a pattern would be use what is known as the Kleene Star and the Kleene Plus, which essentially represents either 0 or more or 1 or more of the character that it follows(it always follows a character or group). For example, to match the donations above, we can use the pattern \d* to match any number of digits, but a tighter regular expression would be \d+ which ensures that the input string has at least one digit.

These quantifiers can be used with any character or special metacharacters, for example a+(one or more a's), [abc]+(one or more of any a, b, or c character) and .* (zero or more of any character).

lesson 8: Character optional

As you saw in the previous lesson, the Kleene star and plus allow us to match repeated characters in a line.

Another quantifier that is really common when matching and extracting text is the ?(question mark) metachatacter which denotes optionality. This metacharacter allows you to match either zero or one of the preceding character or group. For example, the pattern ab?c will match either the strings "abc" or "ac" because the b is considered optional.

Similar to the dot metacharacter, the question mark is a special character and you will have to escape it using a slash \? to match a plain question mark character in a string.

Lesson 9: All this whitespace

When dealing with real-world input, such as log files and even user input, it's difficult not to encounter whitespace. We use it to format pieces of information to make it easier to read and scan visually, and a single space can put a wrench into the simplest regular expression.

The most common forms of whitespace you will use with regular expressions are the space, the tab(\t), the new line(\n) and the carriage returrn (\r)(useful in Windows environments), and these special characters match each of their respective whitespaces. In addition, a whitespace special character \s will match any of the specific whitespaces above and is extremely useful when dealing with raw input text.

Lesson 10: Starting and ending

write as specific regular expressions as possible to ensure that we don't get false positives when matching against real world text.

One way to tighten our patterns is to define a pattern that describes both the start and the end of the line using the special ^(hat) and $(dollar) metacharacters. In the example above, we can use the pattern ^success to match only a line that begins with the word "success", but not the line dollar sign, you create a pattern that matches the whole line completely at the beginning and end.

Lesson 11: Match groups

Regular expression allow us to not just match text but also to extract information for further processing. This is done by defining groups of characters and capturing them using the special parentheses(and) metacharacters. Any subpattern inside a pair of parentheses will be captured as a group. In Practice, this can be used to extract information like phone numbers or emails from all sorts of data.

Imagine for example that you had a command line tool to list all the image files you have in the cloud. you could then use a pattern such as ^(IMG\d+\.png)$ to capture and extract the full filename, but if you only wanted to capture the filename without the extension, you could use the pattern ^(IMG\d+)\.png$ which only captures the part before the period.

Lesson 12 : Nested groups

When you are working with complex data, you can easily find yourself having to extract multiple layers of information, which can result in nested groups. Generally, the results of the captured groups are in the order in which they are defined(in order by open parenthesis).

Take the example from the previous lesson, of capturing the filenames of all the image files you have in a list. If each of these image files had a sequential picture number in the filename, you could extract both the filename and the picture number using the same pattern by writing an expression like ^(IMG(\d+))\.png$(using a nested parenthesis to capture the digits).

The nested groups are read from left to right in the pattern, with the first capture group being the contents of the first parentheses group, etc.

Lesson 13: More group work

As you saw in the previous lessons, all the quantifiers including the star*, plus +, repetition {m,n} and the question mark ? can all be used within the capture group patterns. This is the only way to apply quantifiers on sequences of characters instead of the individual characters themselves.

For example, if I knew that a phone number may or may not contain an area code, the right pattern would test for the existence of the whole group of digits (\d{3})? and not the individual characters themselves(which would be wrong).

Lesson14: It's all conditional

As we mentioned before, it's always good to be precise, and that applies to coding, talking, and even regular expressios. For example, you wouldn't write a grocery list for someone to Buy more .* because you would have no idea what you could get back. Instead you would write Buy more milk or Buy more bread, and in regular expressions, we can actually define these conditions explicitly.

Specifically when using groups, you can use the | (logical OR,aka. the pipe) to denote different possible sets of characters. In the above example, I can write the pattern "Buy more(milk|bread|juice)" to match only the strings Buy more milk, Buy more bread, or Buy more juice.

Like normal groups, you can use any sequence of characters or metacharacters in a condition, for example, ([cb]ats*|[dh]ogs?) would match either cats or bats, or, dogs or hogs. Writing patterns with many condition can be hard to read, so you should consider making them separate if they get too complex.

Lesson15: Other special characters

This lesson will cover some extra metacharacters, as well as the results of captured groups.

We have already learned the most common metacharacters to capture digits using \d, whitespace using \s, and alphanumeric letters and digits using \w, but regular expressions also provides a way of specifying the opposite sets of each of these metacharacters by using their upper case letters. For example,\D represents any non-digit, \S any non-whitespace character, and \W any non-alphanumeric character(such as punctuation). Depending on how you compose your regular expression, it may be easier to use one or the other.

Additionally, there is a special metacharacter \b which matches the boundary between a word and a non-word character. It's most useful in capturing entire words(for example by using the pattern \w+\b).

One concept that we will not explore in great detail in these lessons is back referencing, mostly because it varies depending on the implementation. However, many systems allow you to reference your captured groups by using \0(usually the full matched text), \1(group1), \2(group 2), etc. This is useful for example when you are in a text editor and doing a search and replace using regular expressions to swap two numbers, you can search for "(\d+)-(\d+)" and replace it with "\2-\1" to put the second captured number first, and the first captured number second for example.