Chapter 9 Virtual Memory

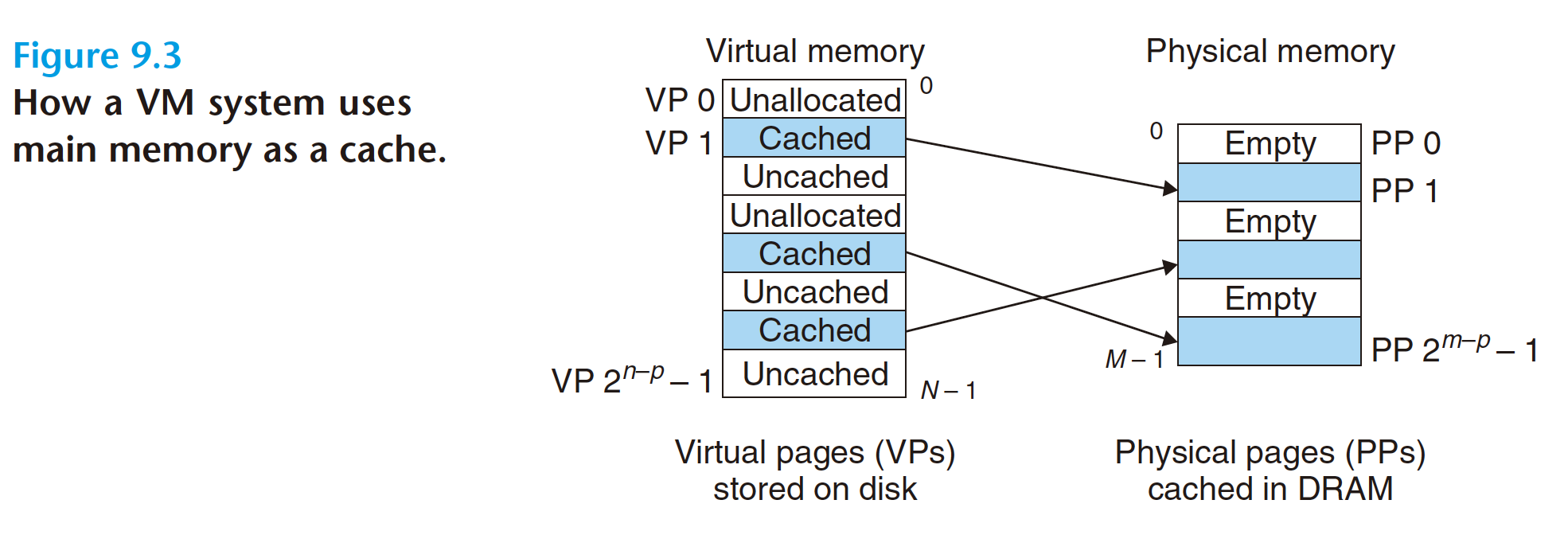

- It uses main memory efficiently by treating it as a cache for an address space stored on disk, keeping only the active areas in main memory and transferring data back and forth between disk and memory as needed.

- It simplifies memory management by providing each process with a uniform address space.

- It protects the address space of each process from corruption by other processes.

9.1 Physical and Virtual Addressing

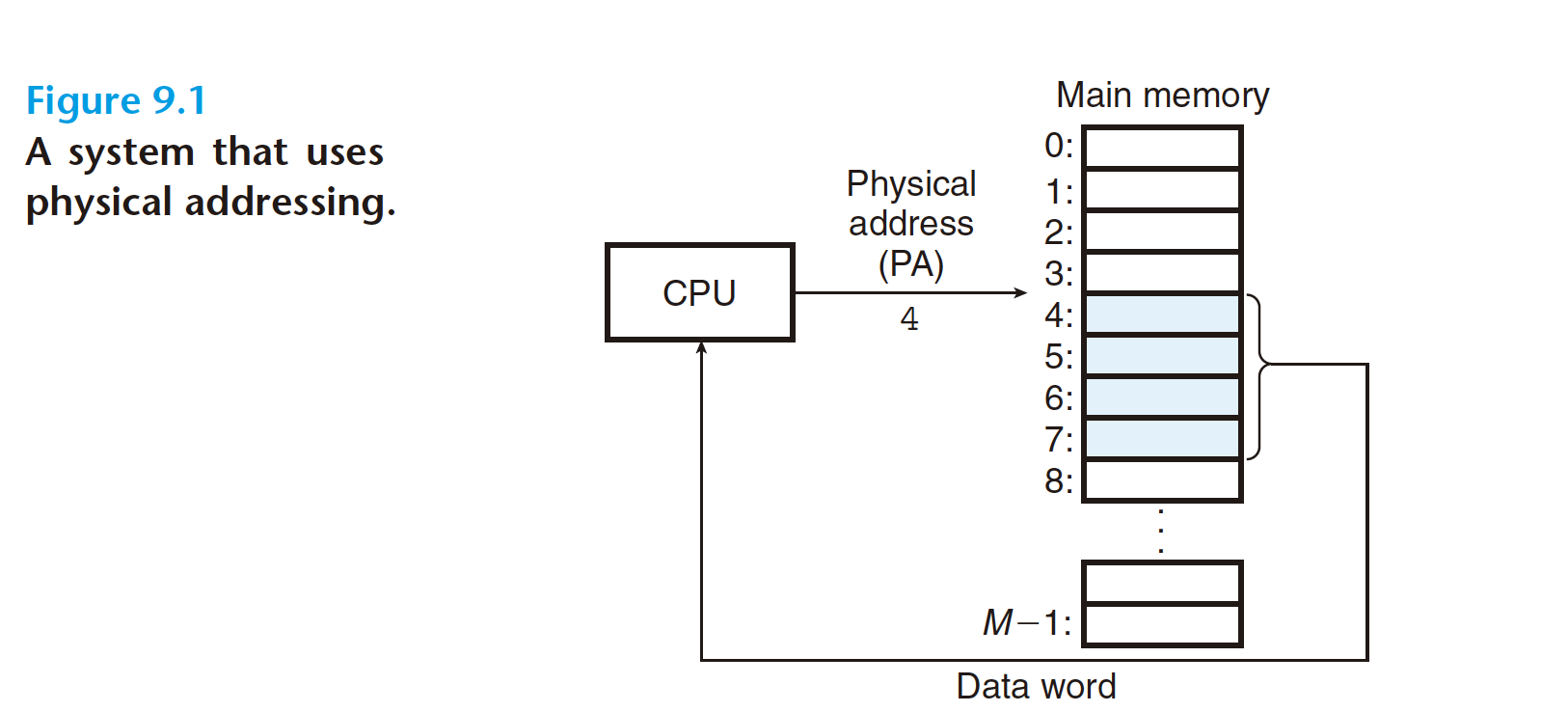

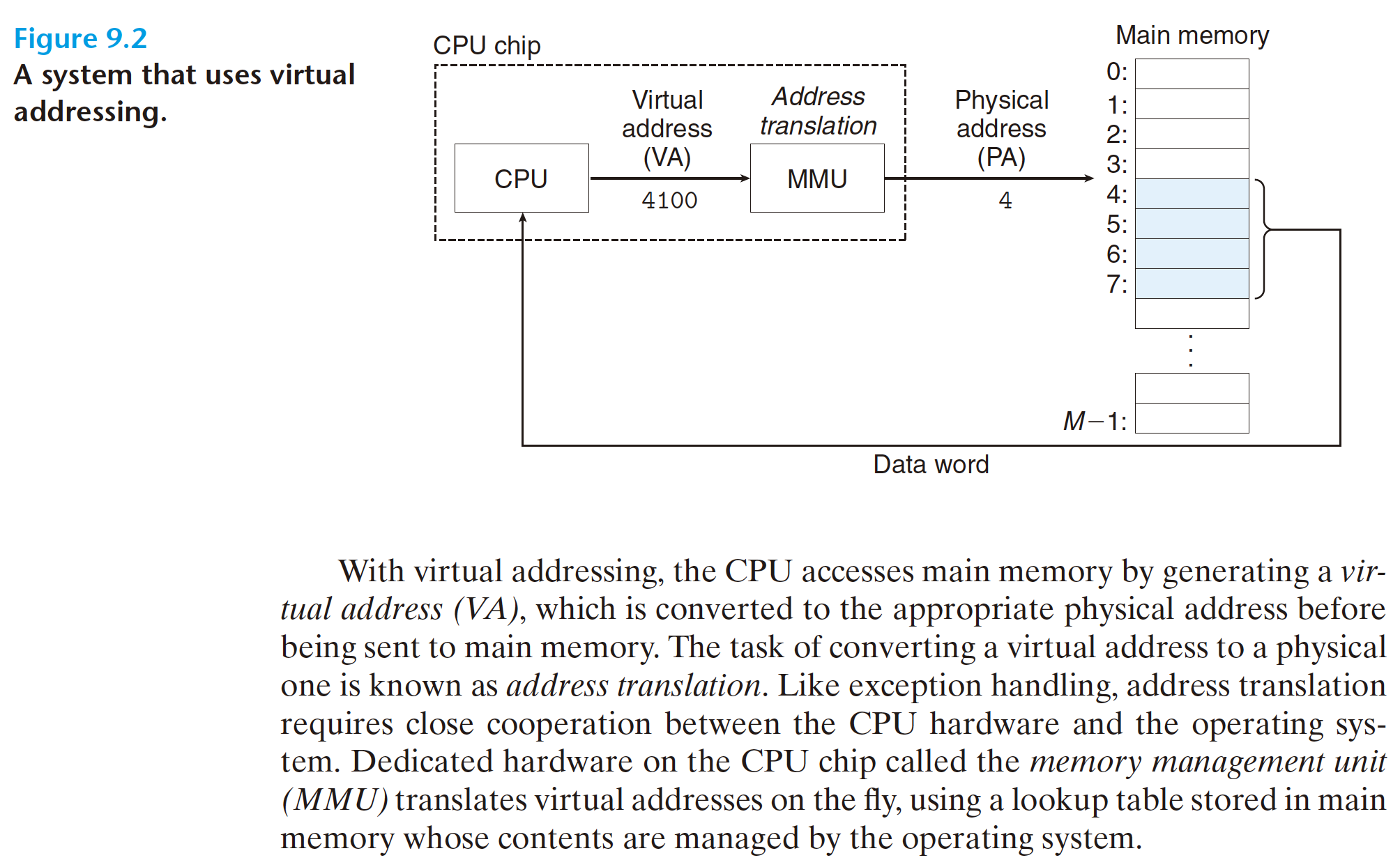

Early PCs used physical addressing, and systems such as digital signal processors,

embedded microcontrollers, and Cray supercomputers continue to do so. However, modern processors use a form of addressing known as virtual addressing, as shown in Figure 9.2.

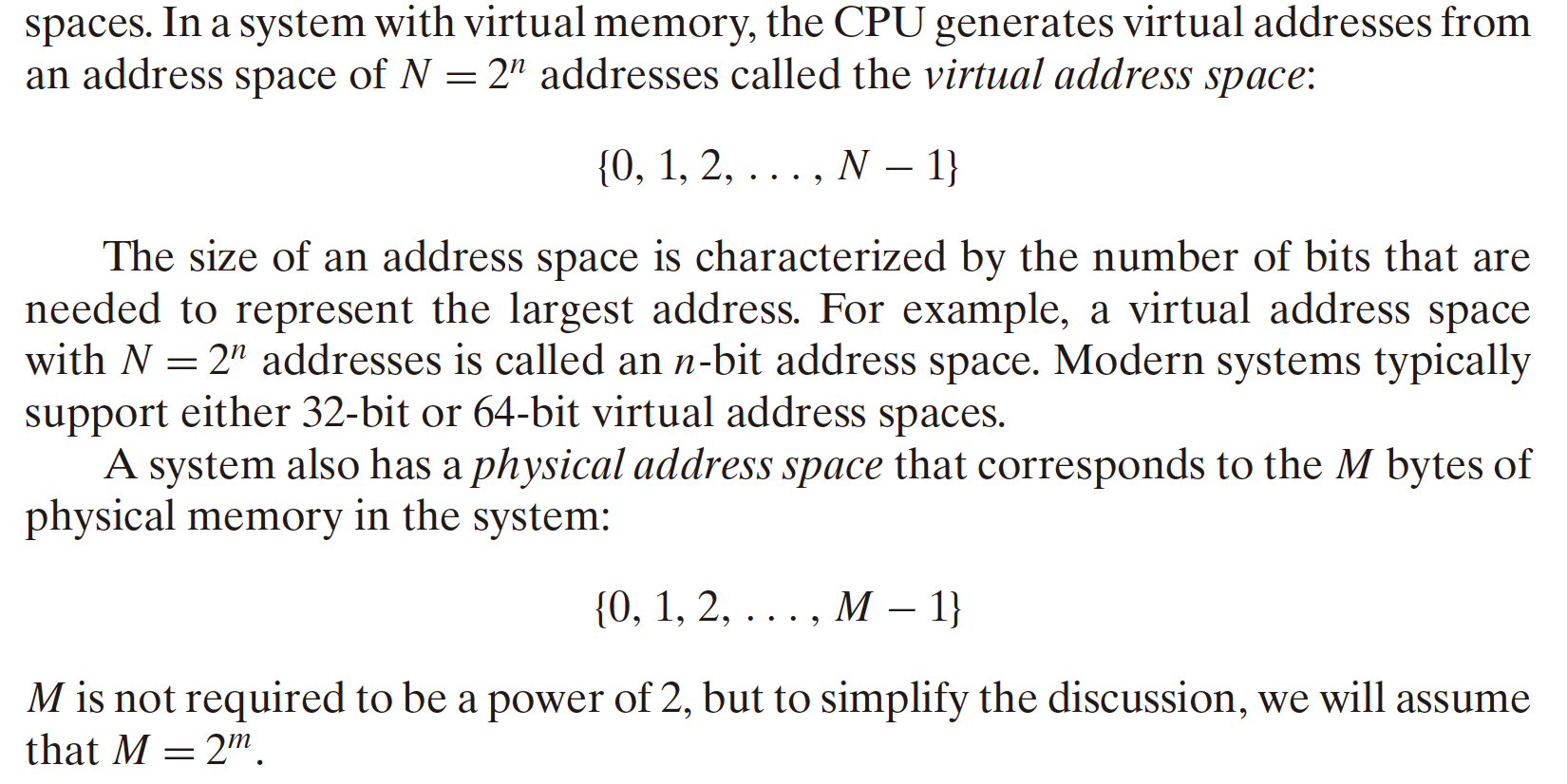

9.2 Address Spaces

9.3 VM as a Tool for Caching

9.3.1 DRAM Cache Organizaiton

9.3.2 Page Tables

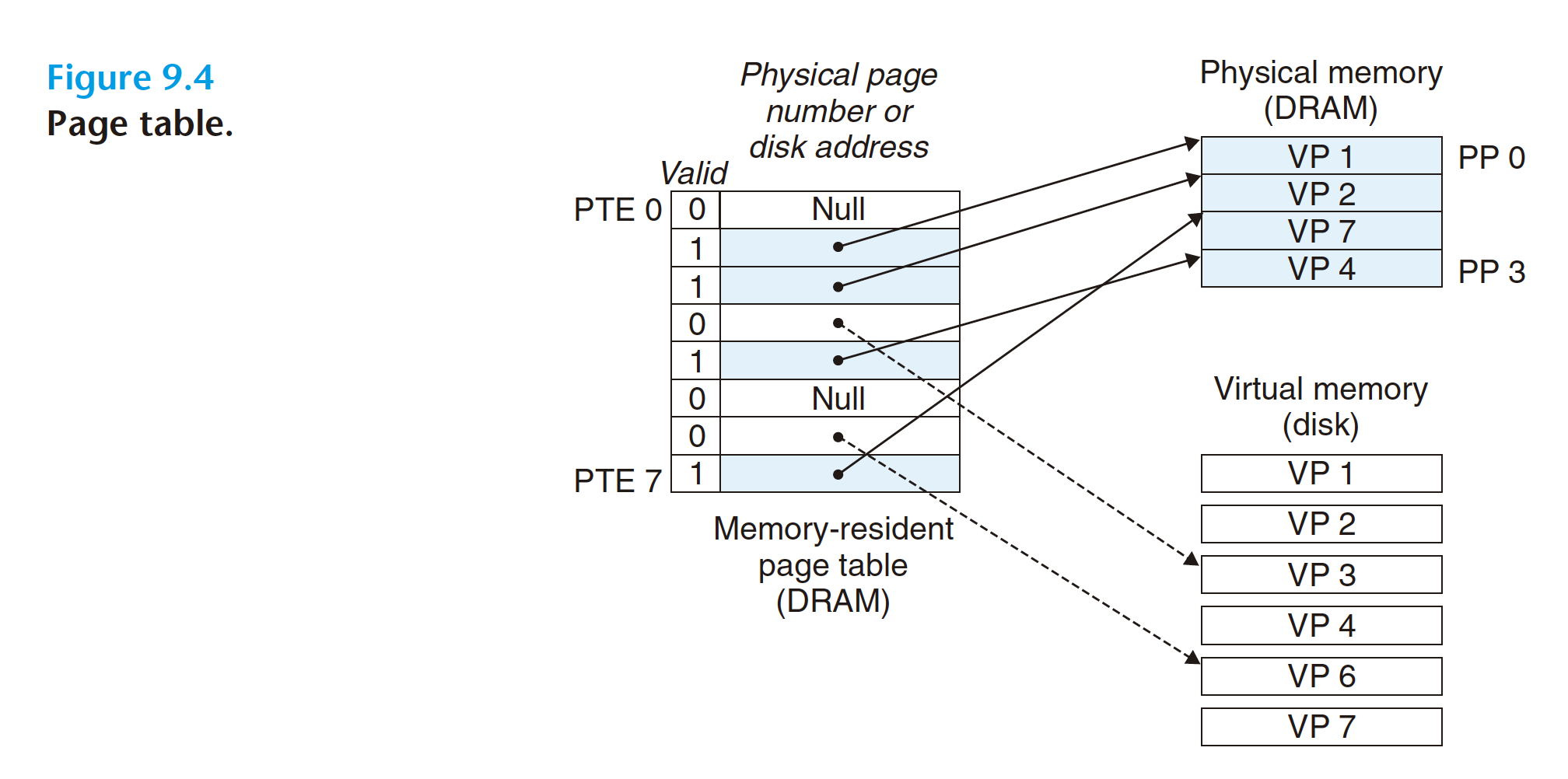

Each page in the virtual address space has a PTE at a fixed offset in the page table. For our purposes, we will assume that each PTE consists of a valid bit and an n-bit address field. The valid bit indicates whether the virtual page is currently cached in DRAM.

If the valid bit is set, the address field indicates the start of the corresponding physical page in DRAM where the virtual page is cached. If the valid bit is not set, then a null address indicates that the virtual page has not yet been allocated. Otherwise, the address points to the start of the virtual page on disk.

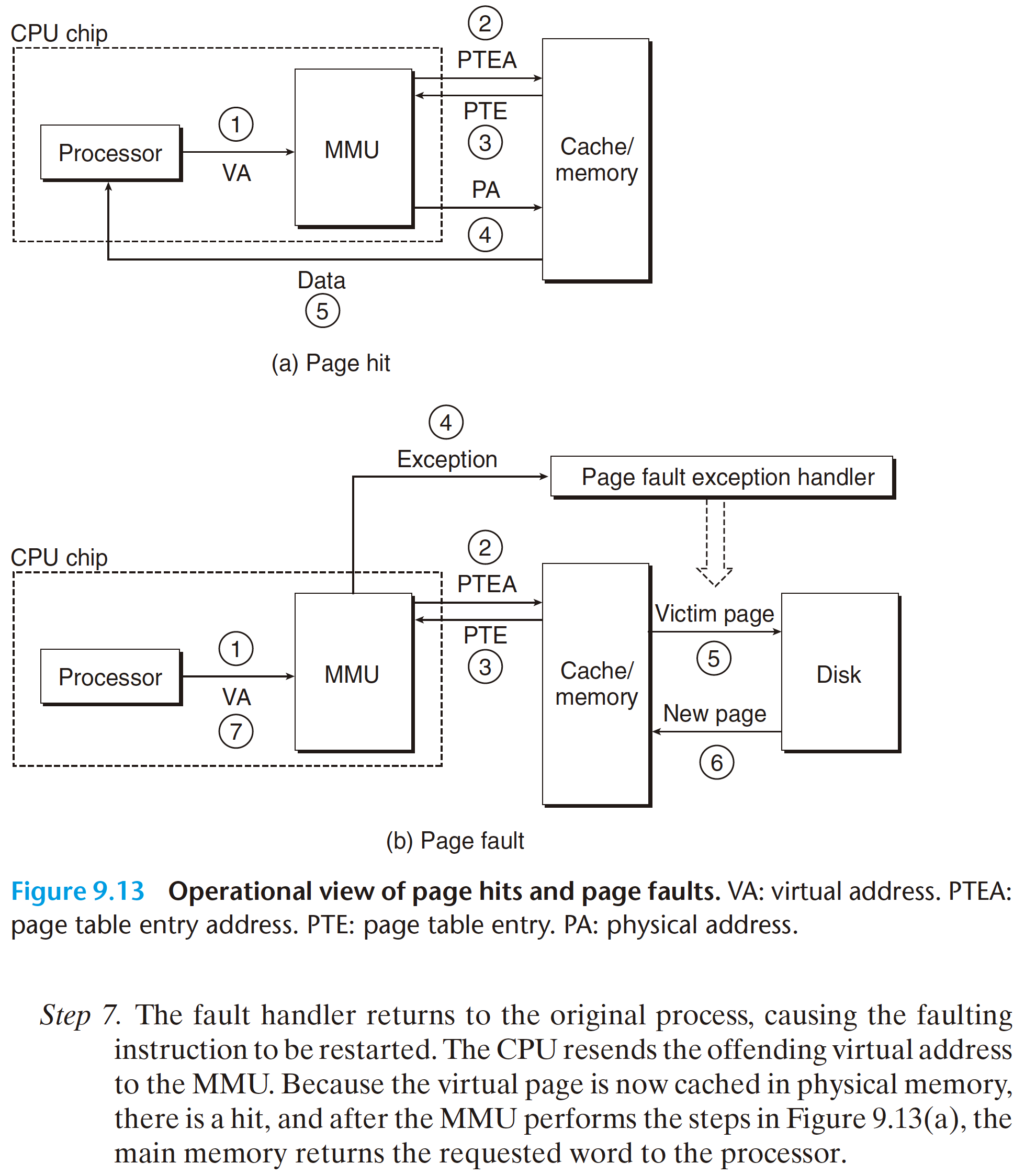

9.3.3 Page Hits

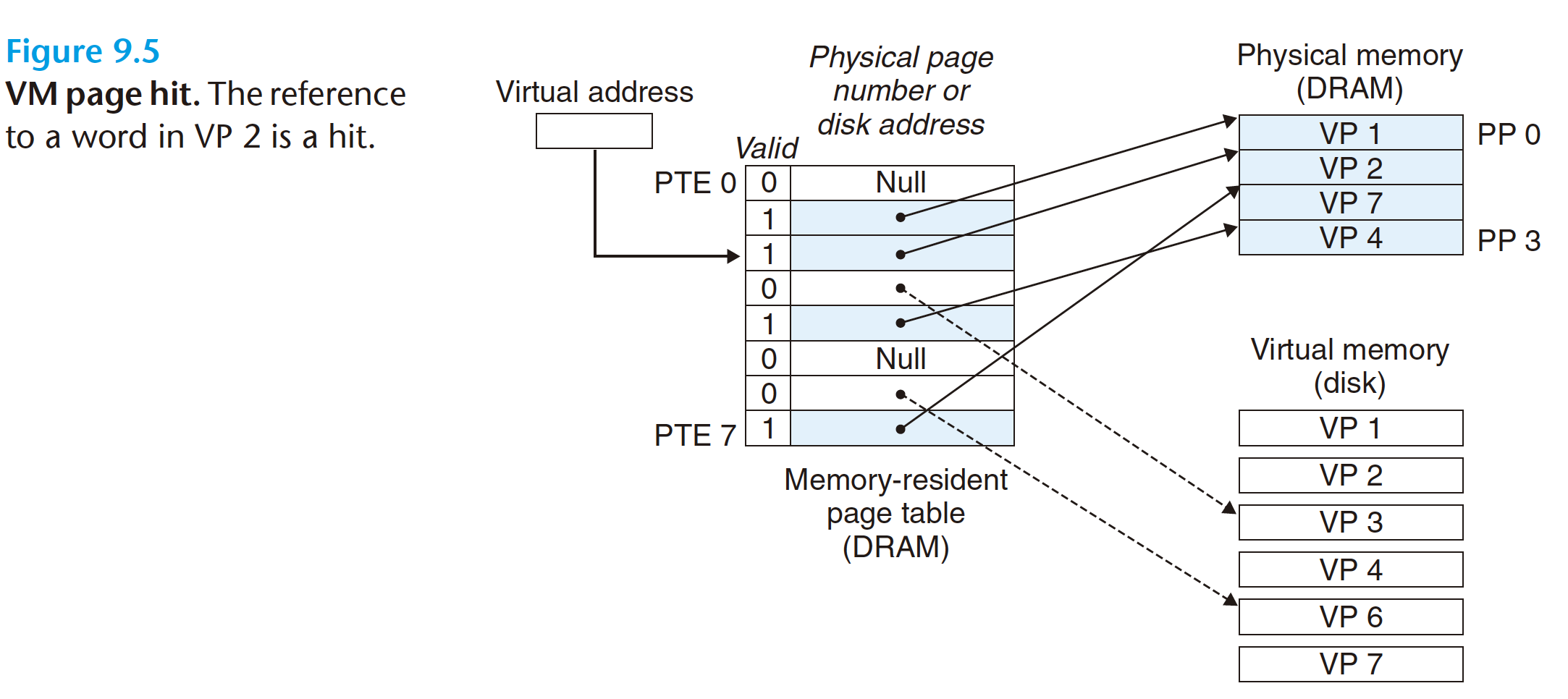

Consider what happens when the CPU reads a word of virtual memory contained

in VP2, which is cached in DRAM(Figure 9.5). Using a technique we will describe

in detail in Section 9.6, the address translation hardware uses the virtual address

as an index to locate PTE 2 and read it from memory. Since the valid bit is set, the

address translation hardware knows that VP 2 is cached in memory. So it uses the

physical memory address in the PTE (which points to the start of the cached page

in PP 1) to construct the physical address of the word.

9.3.4 Page Faults

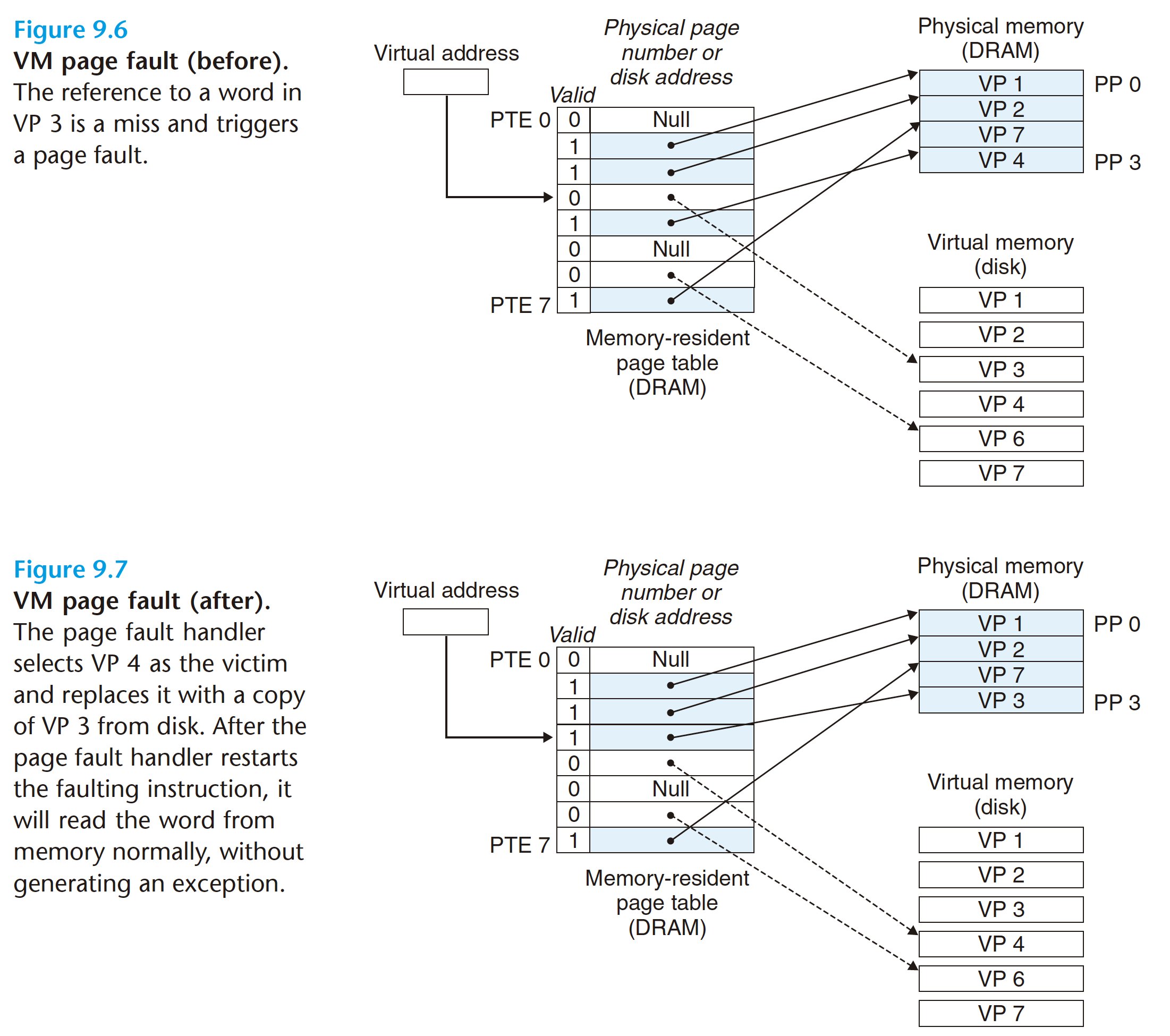

The activity of transferring a page between disk and memory is known as swapping or paging. Pages are swapped in (paged in) from disk to DRAM, and swapped out (paged out) from DRAM to disk.

9.3.5 Allocating Pages

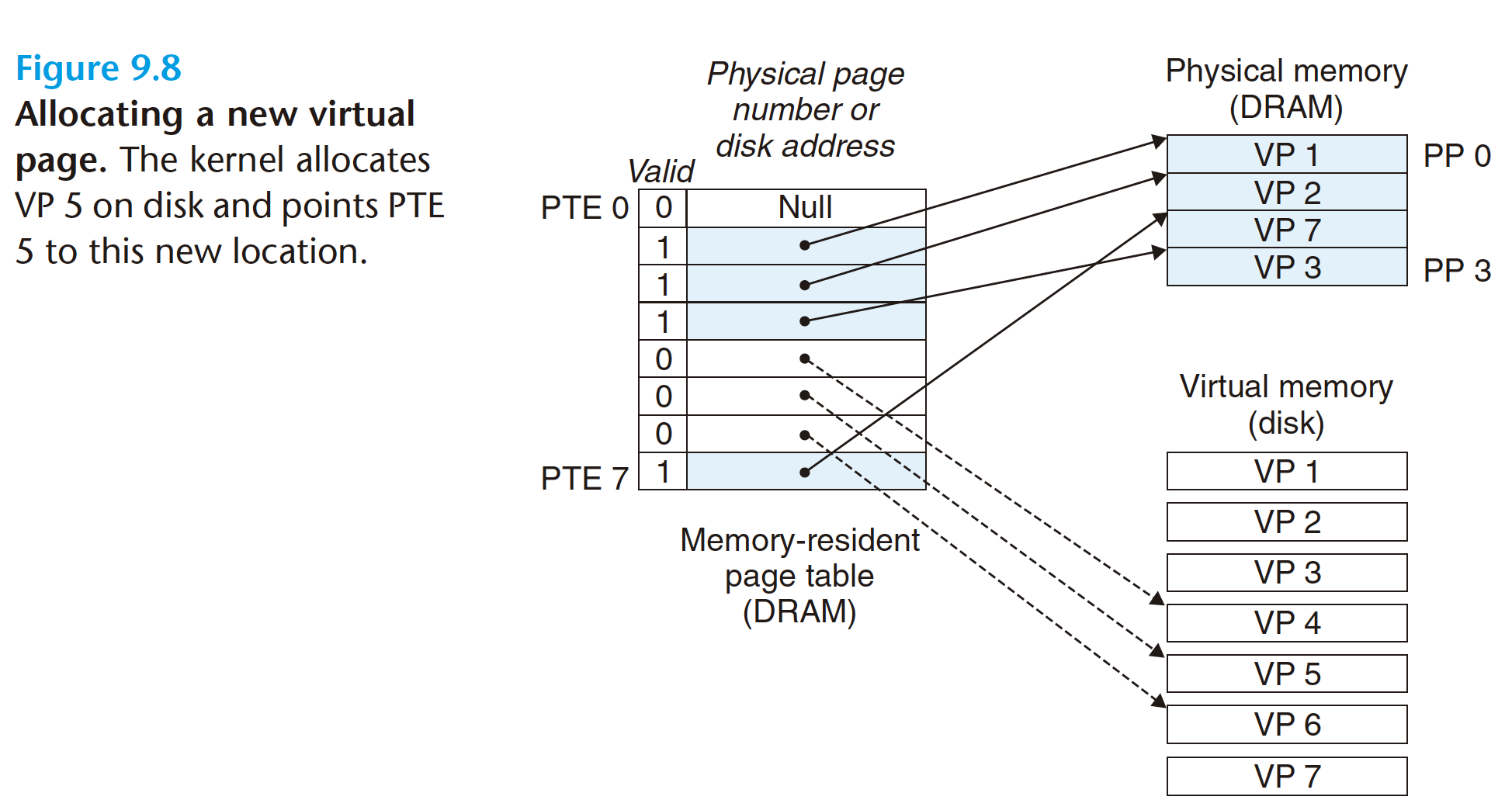

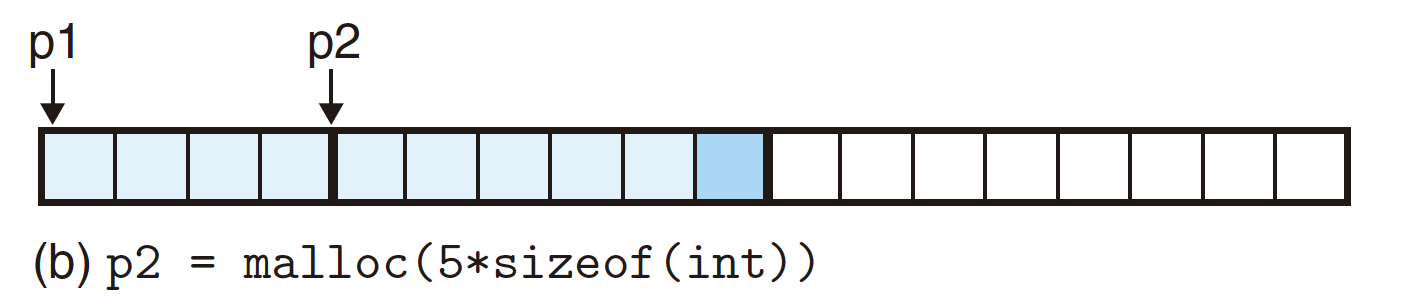

Figure 9.8 shows the effect on our example page table when the operating system

allocates a new page of virtual memory—for example, as a result of calling malloc.

In the example, VP 5 is allocated by creating room on disk and updating PTE 5

to point to the newly created page on disk.

9.3.6 Locality to the Rescue Again

9.4 VM as a Tool for Memory Management

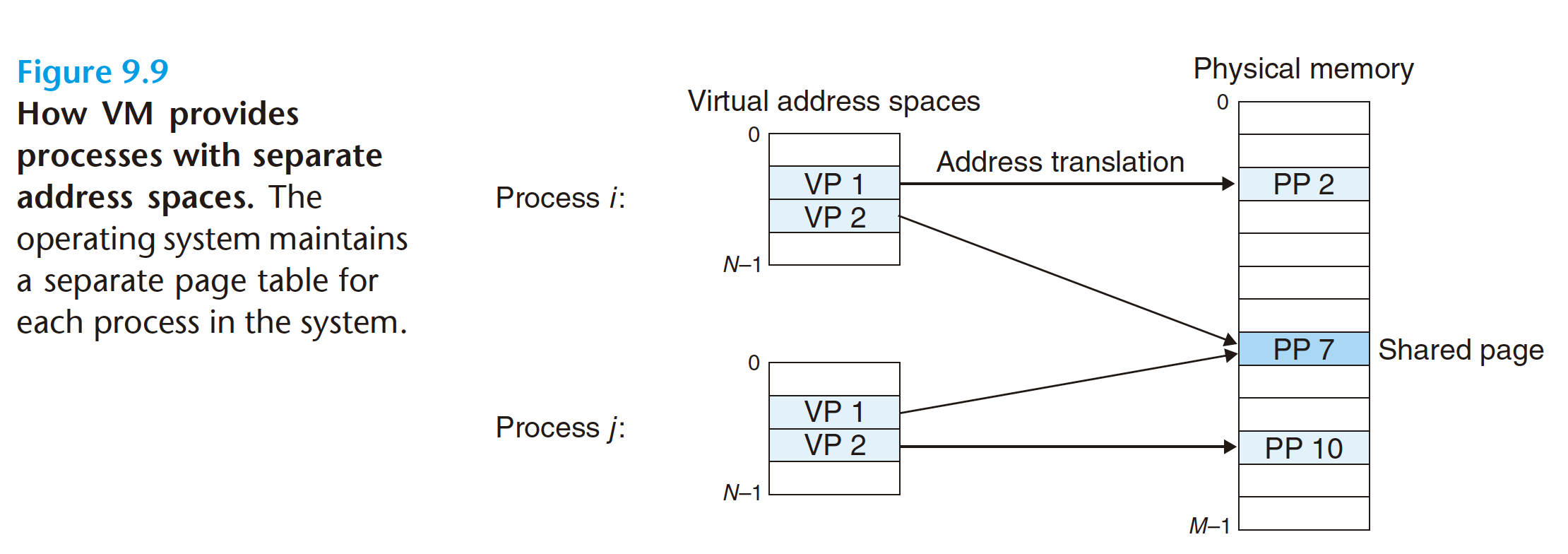

In fact, operating systems provide a separate page table, and thus a separate virtual address space, for each process. Notice that multiple virtual pages can be mapped to the same shared physical page.

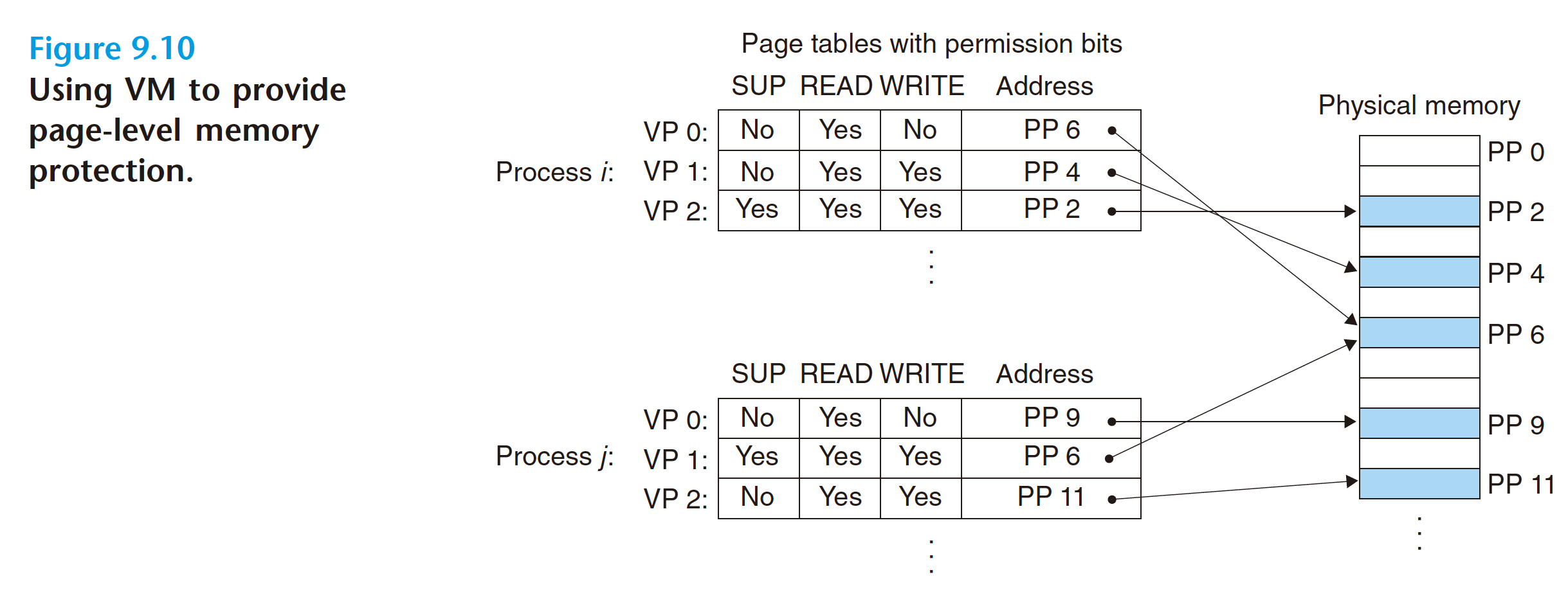

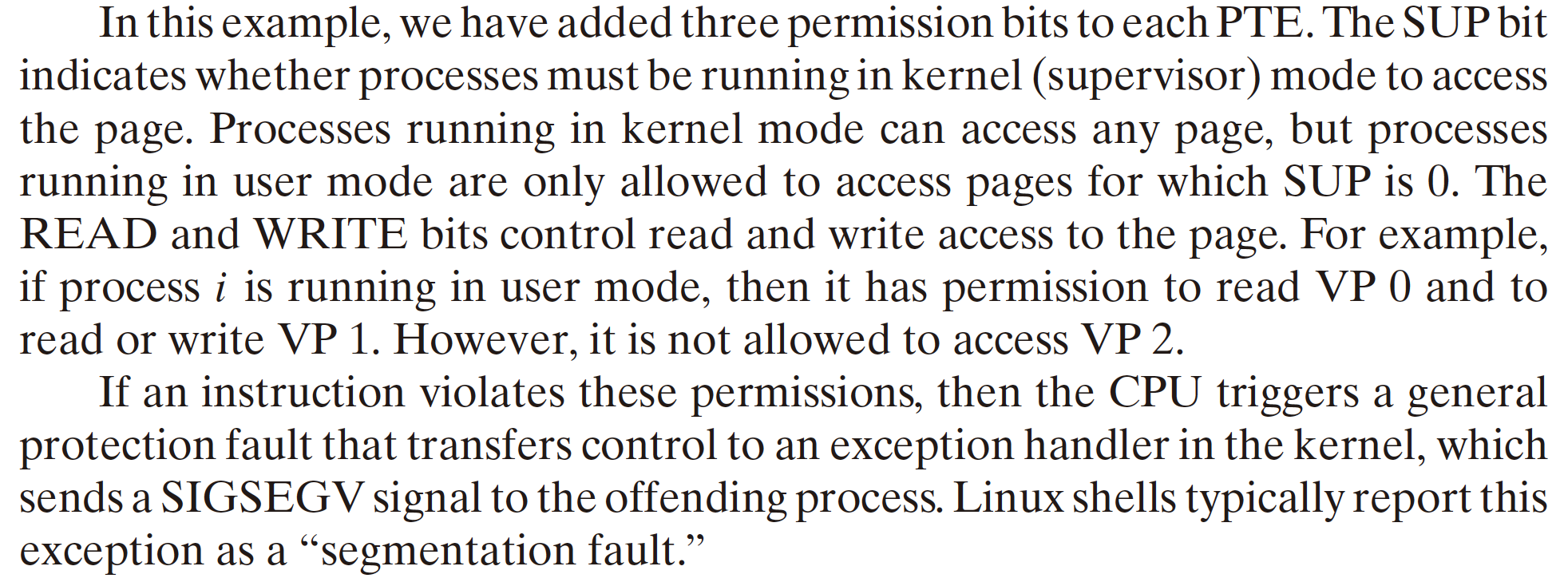

9.5 VM as a Tool for Memory Protection

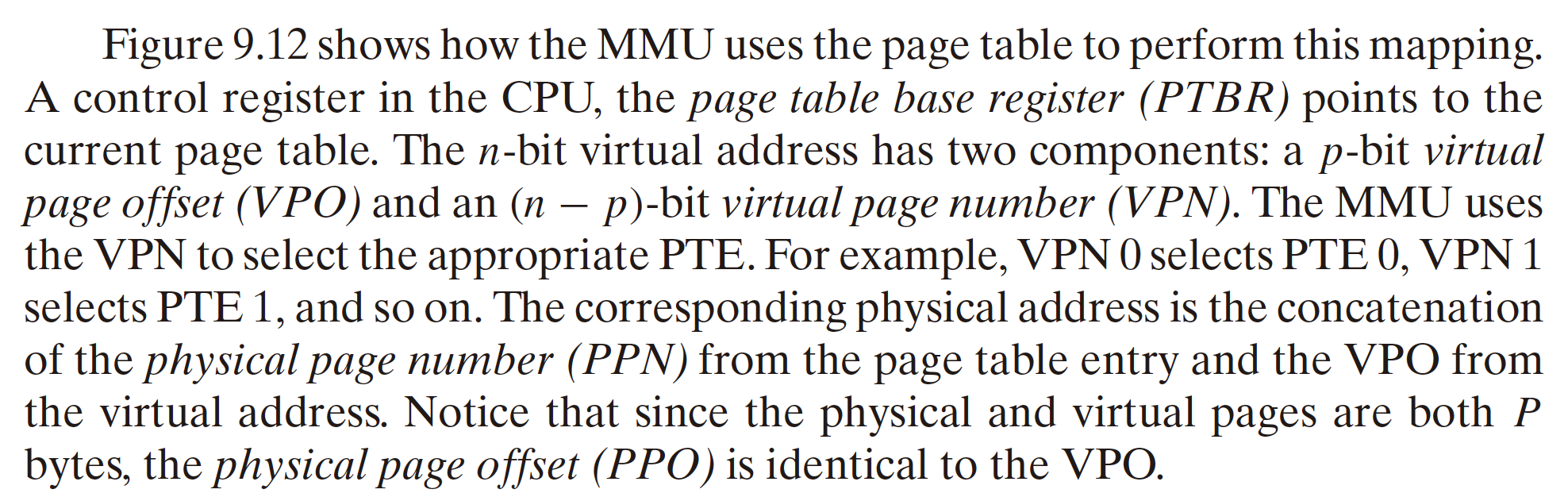

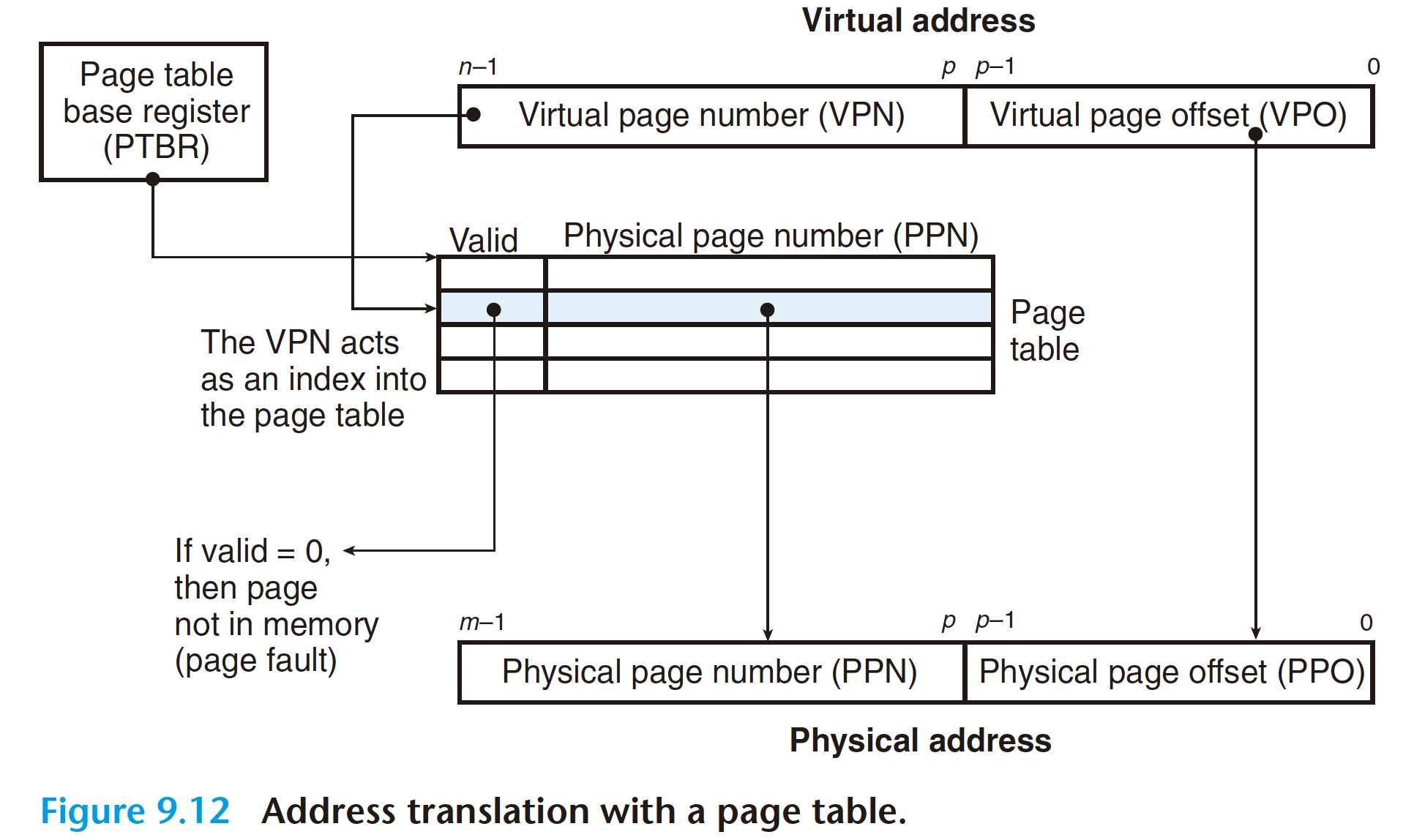

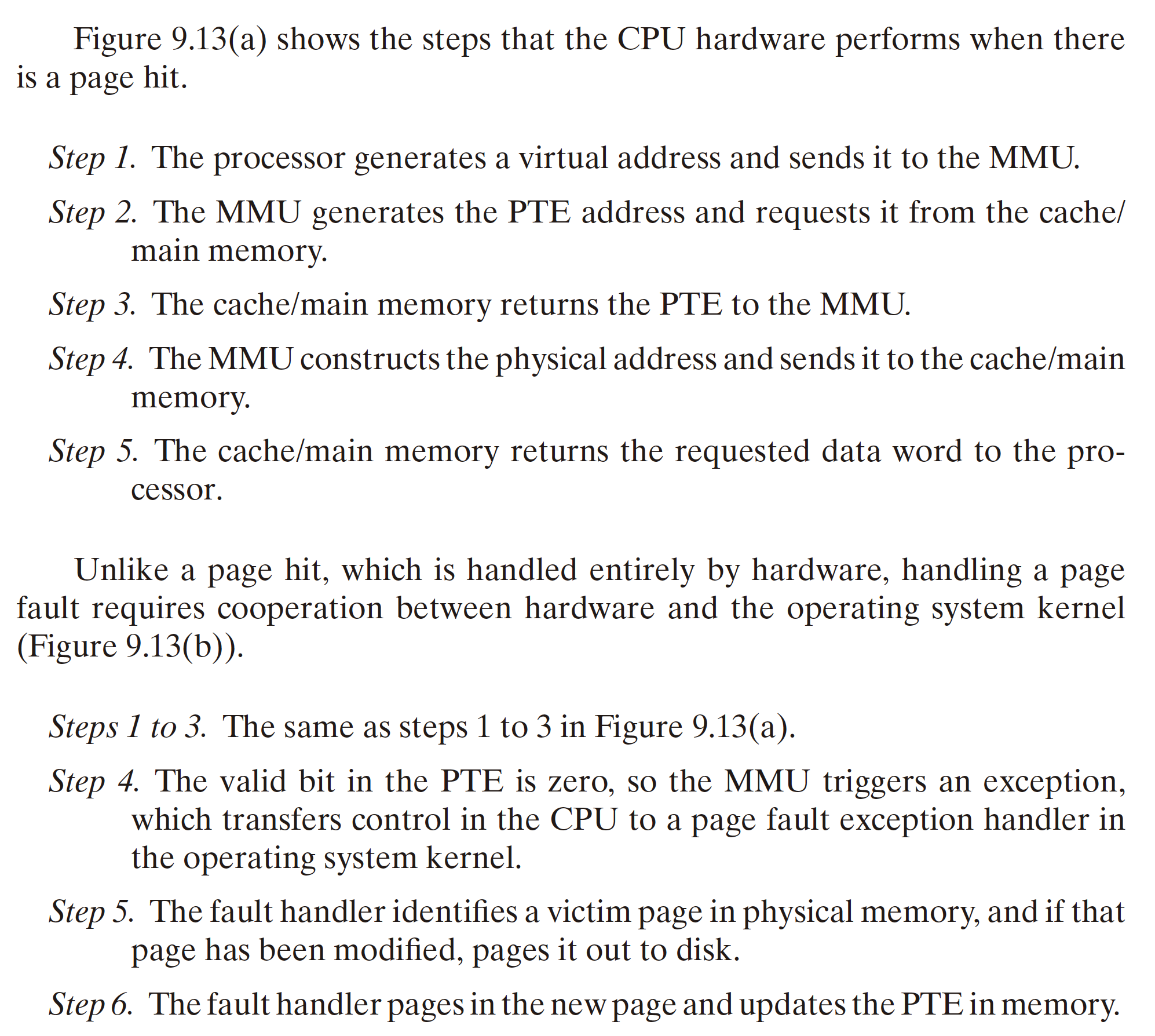

9.6 Address Translation

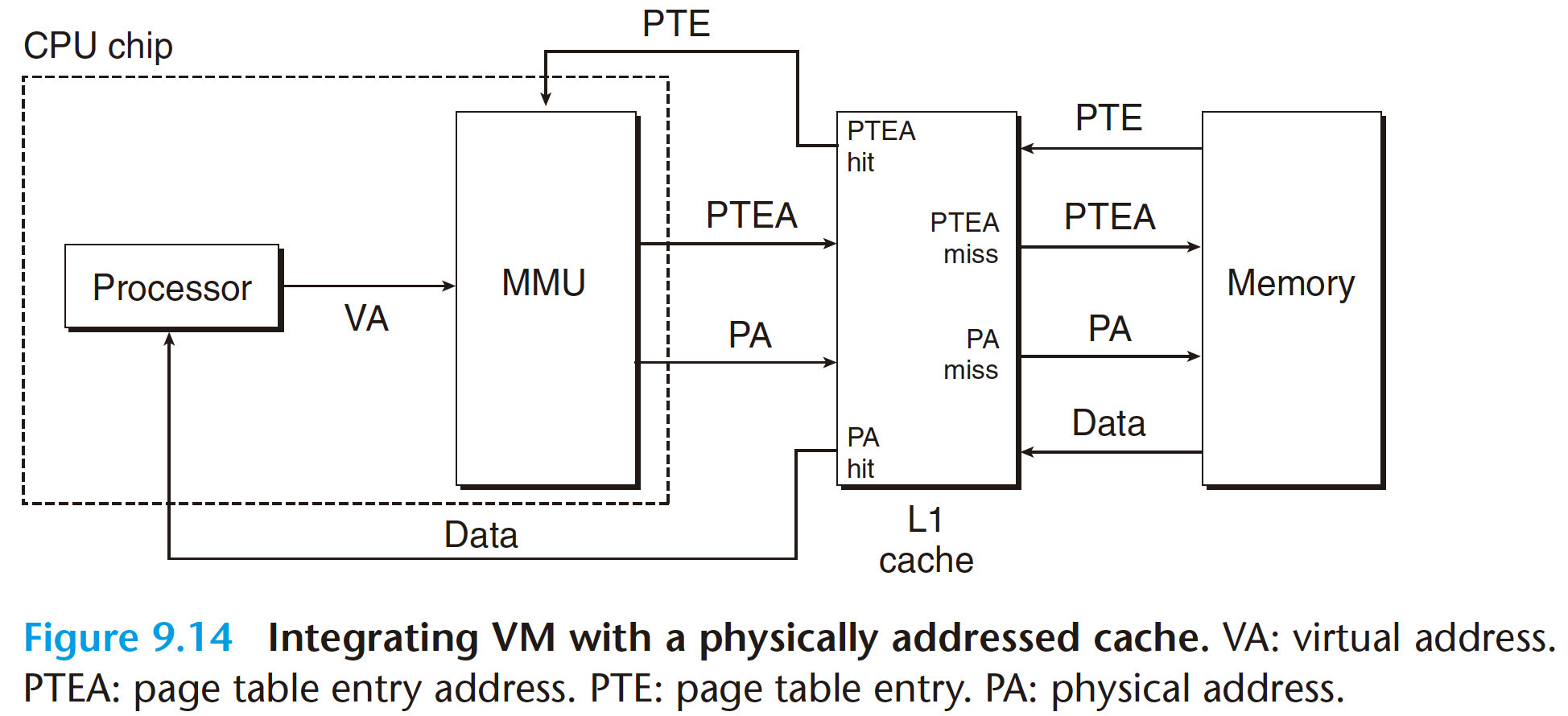

9.6.1 Integrating Caches and VM

The main idea is that the address translation occurs before the cache lookup. Notice that page table entries can be cached, just like any other data words.

The main idea is that the address translation occurs before the cache lookup. Notice that page table entries can be cached, just like any other data words.

9.6.2 Speeding Up Address Translation with a TLB

A TLB is a small, virtually addressed cache where each line holds a block consisting of a single PTE.

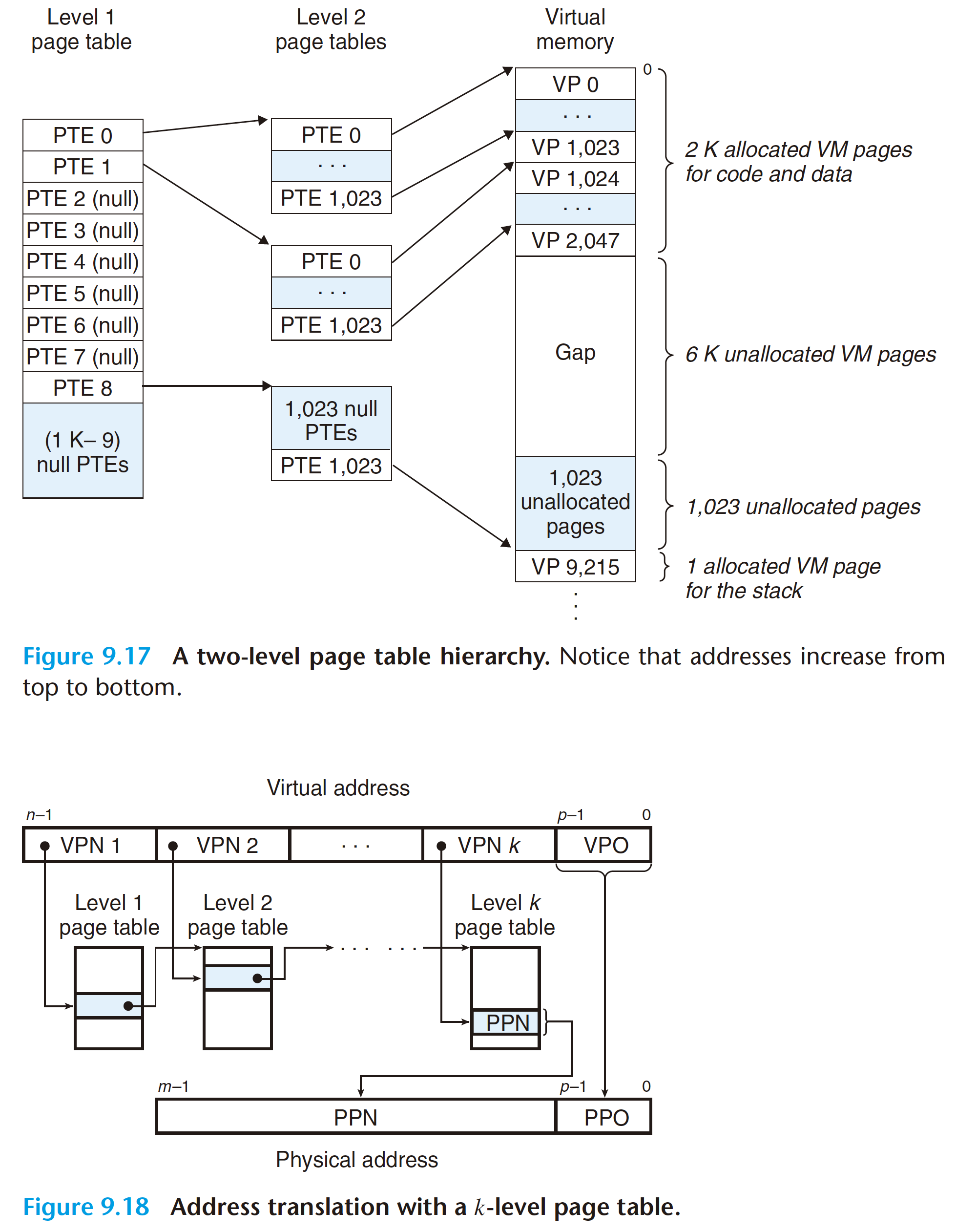

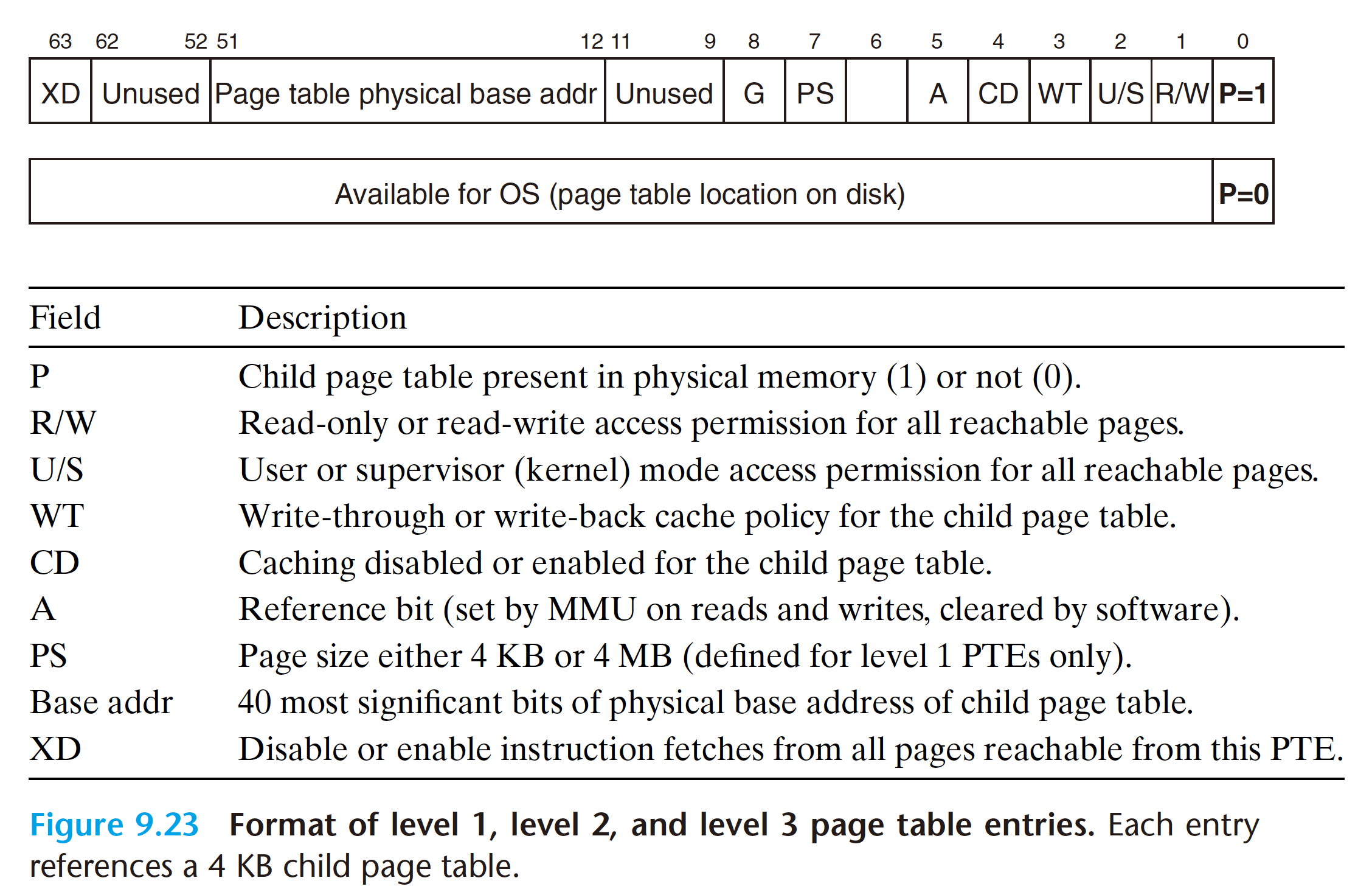

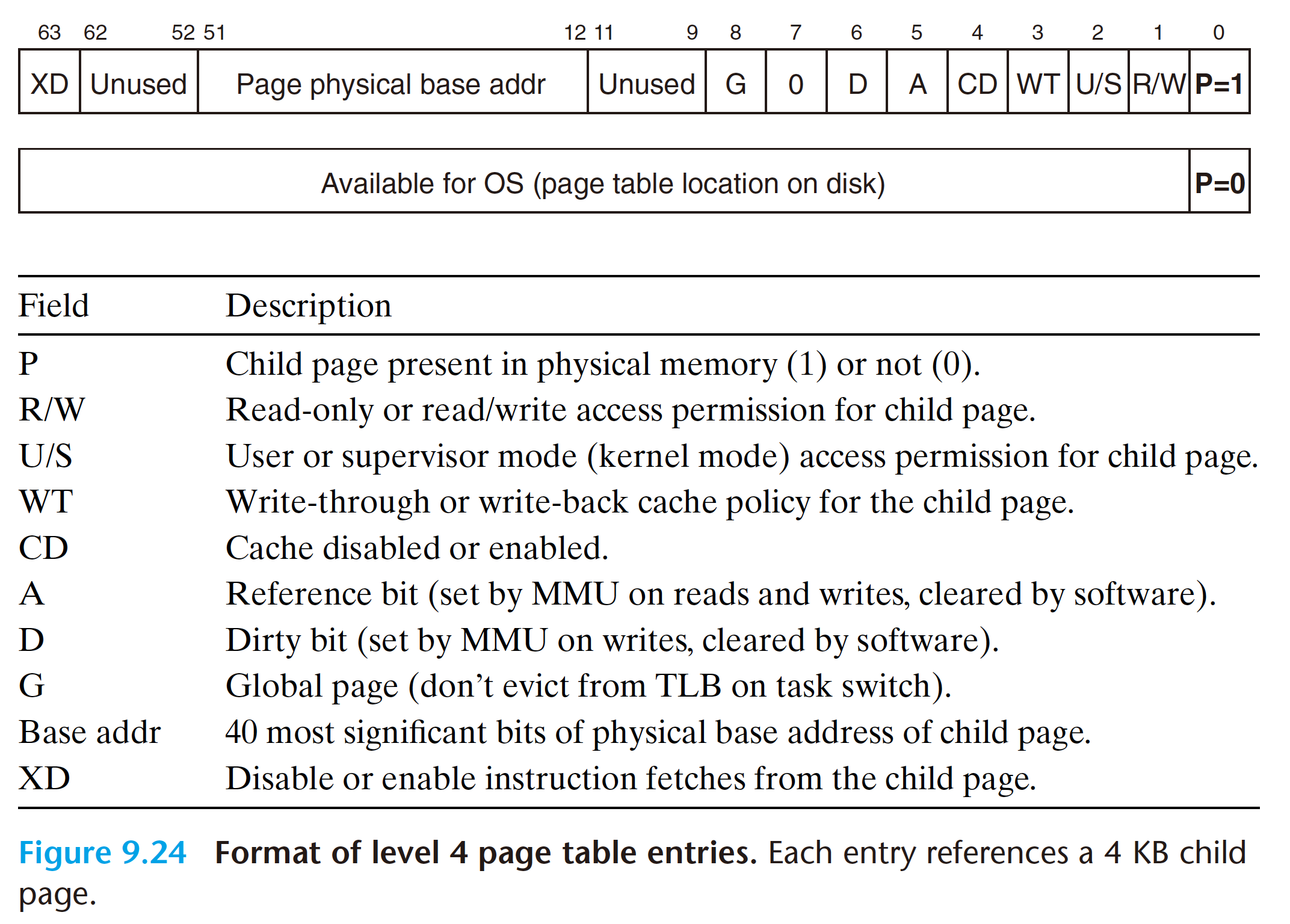

9.6.3 Multi-Level Page Tables

This scheme reduces memory requirements in two ways. First, if a PTE in the level 1 table is null, then the corresponding level 2 page table does not even have to exist. This represents a significant potential savings, since most of the 4 GB virtual address space for a typical program is unallocated. Second, only the level 1 table needs to be in main memory at all times. The level 2 page tables can be created and paged in and out by theVMsystem as they are needed, which reduces pressure on main memory. Only the most heavily used level 2 page tables need to be cached in main memory.

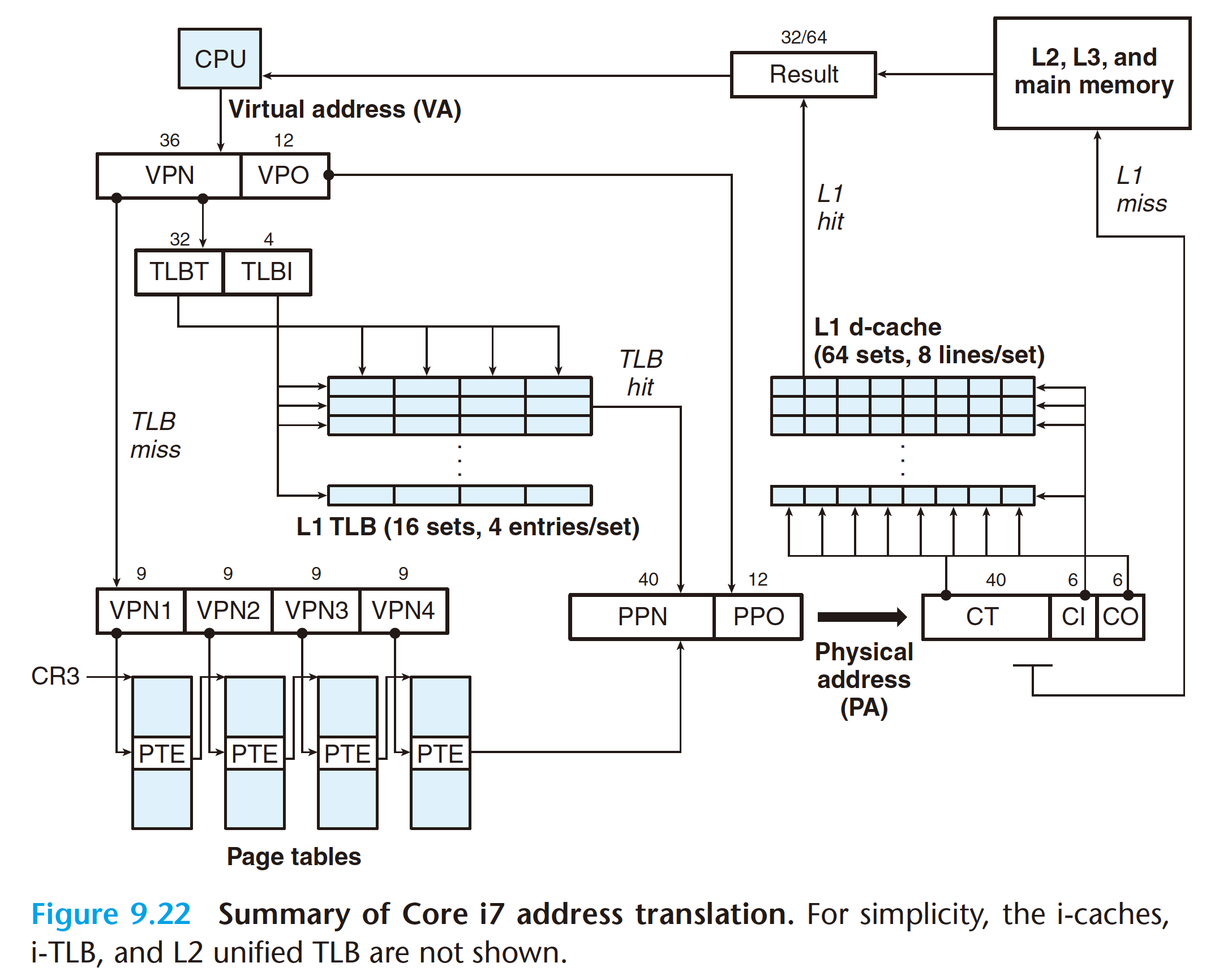

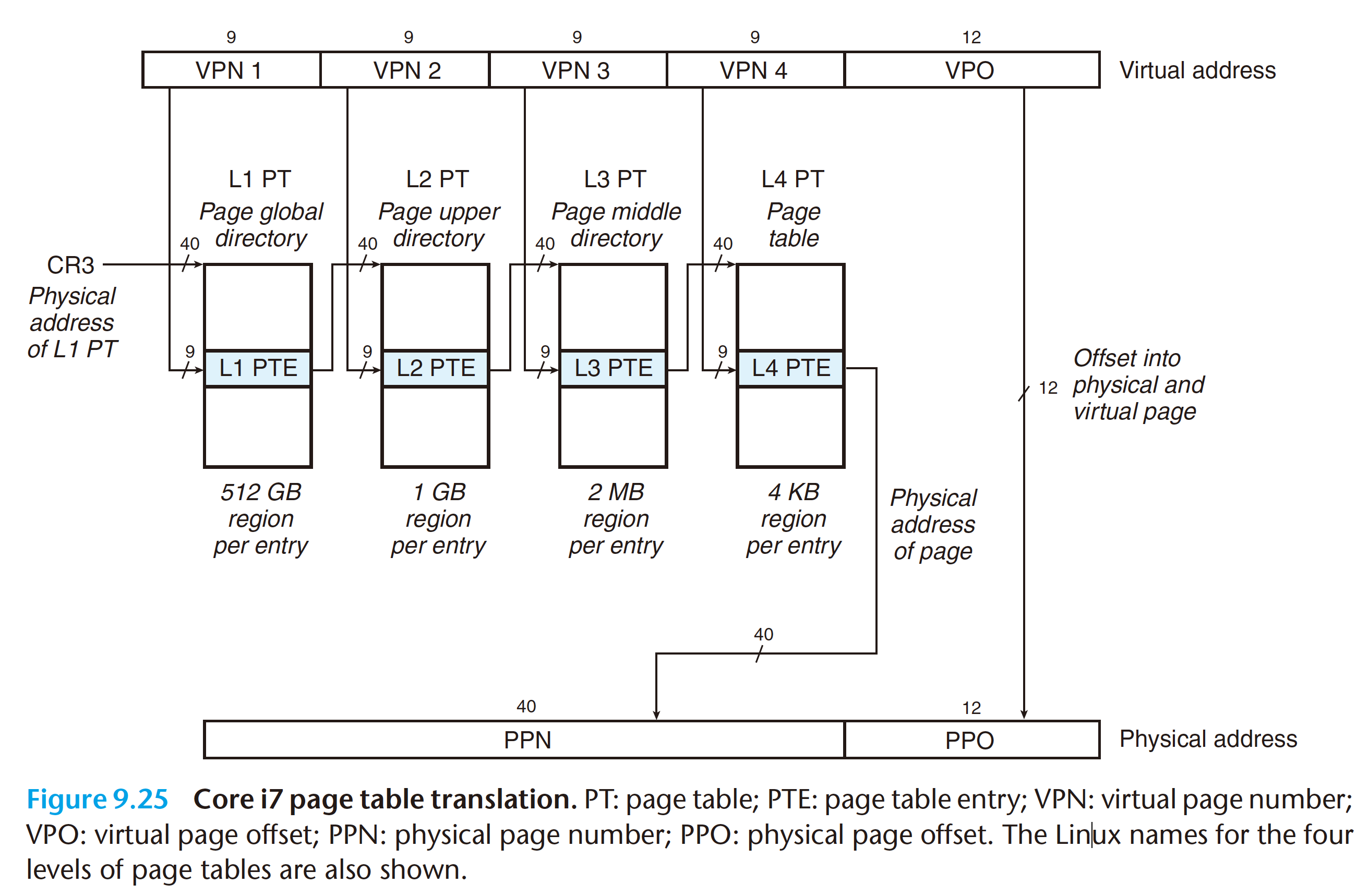

Figure 9.18 summarizes address translation with a k-level page table hierarchy. The virtual address is partitioned into k VPNs and a VPO. Each VPN i, 1 ≤ i ≤ k, is an index into a page table at level i. Each PTE in a level j table, 1 ≤ j ≤ k − 1, points to the base of some page table at level j + 1. Each PTE in a level k table contains either the PPN of some physical page or the address of a disk block. To construct the physical address, the MMU must access k PTEs before it can determine the PPN. As with a single-level hierarchy, the PPO is identical to the VPO.

Accessing k PTEs may seem expensive and impractical at first glance. However, the TLB comes to the rescue here by caching PTEs from the page tables at the different levels. In practice, address translation with multi-level page tables is not significantly slower than with single-level page tables.

9.6.4 Putting it Together: End-to-End Address Translation

9.7 Case Study: The Intel Core i7/Linux Memory System

9.7.1 Core i7 Address Translation

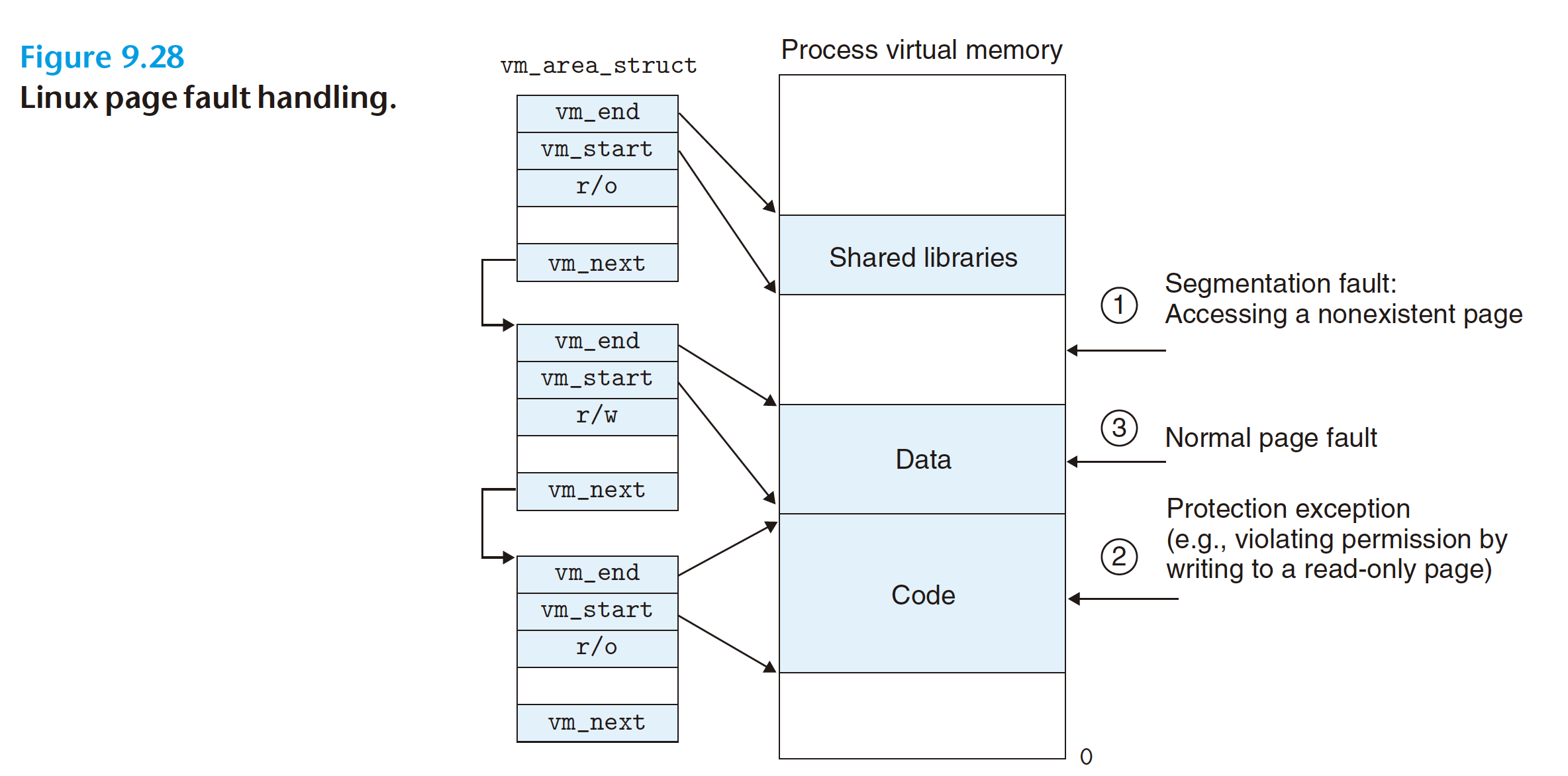

9.7.2 Linux Virtual Memory System

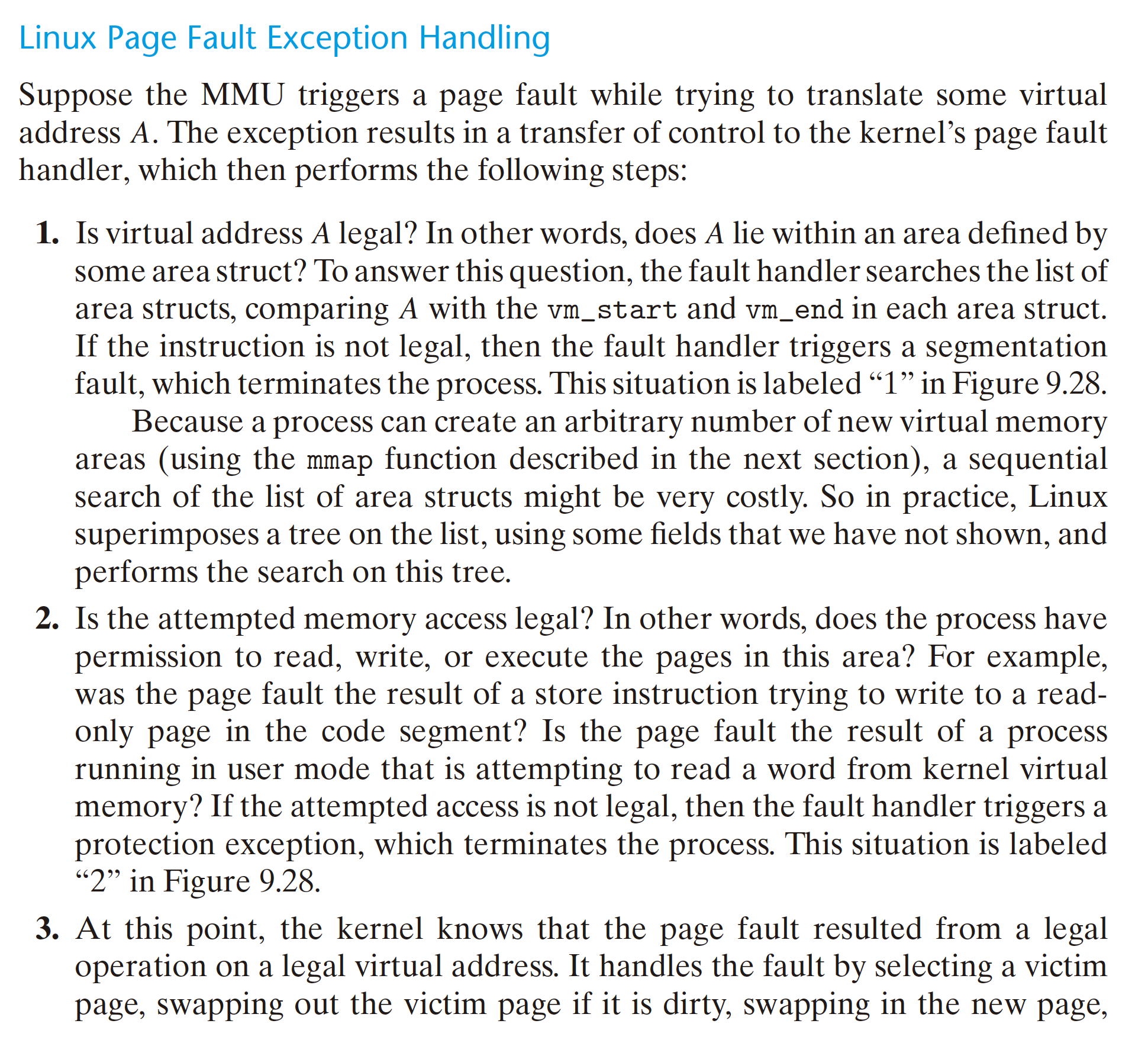

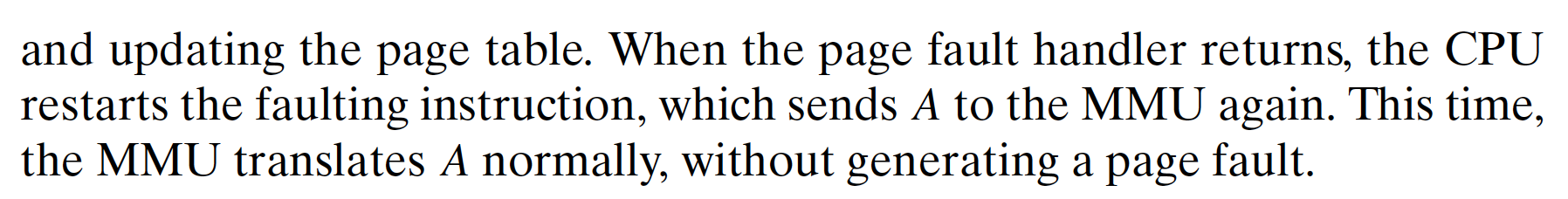

9.8 Memory Mapping

Linux initializes the contents of a virtual memory area by associating it with an

object on disk, a process known as memory mapping.

9.9 Dynamic Memory Allocation

- Explicit allocators require the application to explicitly free any allocated

blocks. For example, the C standard library provides an explicit allocator called the

mallocpackage. C programs allocate a block by calling themallocfunction, and free a block by calling thefreefunction. Thenewanddeletecalls in C++ are comparable. - Implicit allocators, on the other hand, require the allocator to detect when an allocated block is no longer being used by the program and then free the block. Implicit allocators are also known as garbage collectors, and the process of automatically freeing unused allocated blocks is known as garbage collection. For example, higher-level languages such as Lisp, ML, and Java rely on garbage collection to free allocated blocks.

9.10 Garbage Colleciton

9.9.1 The malloc and free Functions

9.9.2 Why Dynamic Memory Allocation

9.9.3 Allocator Requirements and Goals

9.9.4 Fragmentation

The primary cause of poor heap utilization is a phenomenon known as fragmentation, which occurs when otherwise unused memory is not available to satisfy allocate requests. There are two forms of fragmentation: internal fragmentation and external fragmentation.

Internal fragmentation occurs when an allocated block is larger than the payload.

External fragmentation occurs when there is enough aggregate free memory

to satisfy an allocate request, but no single free block is large enough to handle

the request.

if the request in Figure 9.34(e) were for eight words

rather than two words, then the request could not be satisfied without requesting

additional virtual memory from the kernel, even though there are eight free words

remaining in the heap.

if the request in Figure 9.34(e) were for eight words

rather than two words, then the request could not be satisfied without requesting

additional virtual memory from the kernel, even though there are eight free words

remaining in the heap.