Chapter8 Exceptional Control Flow

8.1 Excepitons

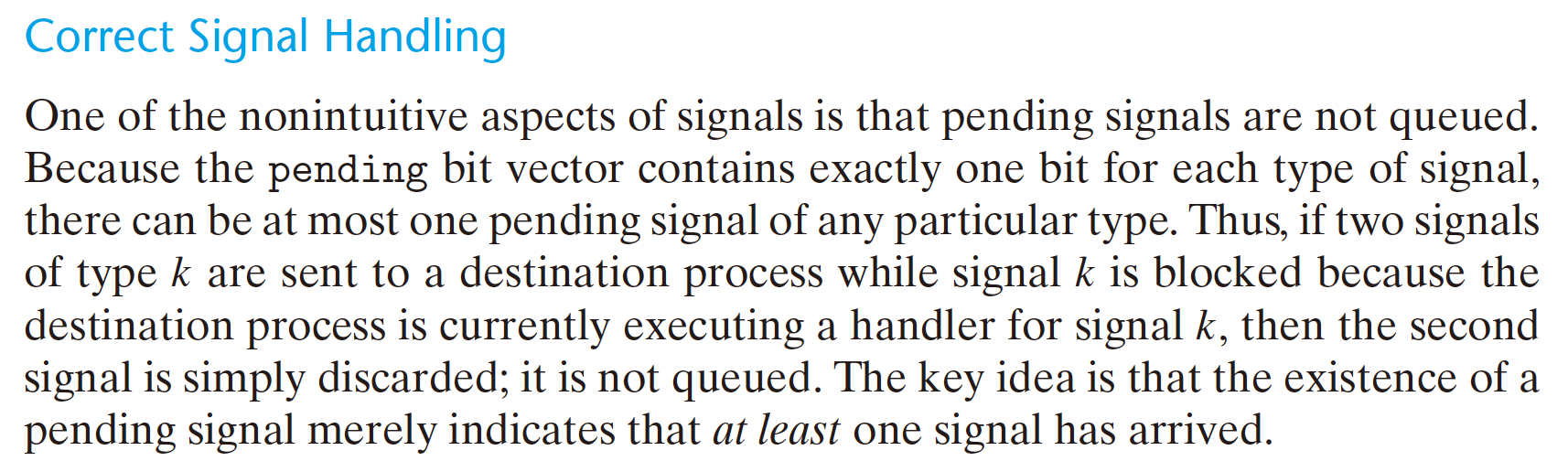

In the figure, the processor is executing some current instruction Icurr when a significant change in the processor’s state occurs. The state is encoded in various bits and signals inside the processor. The change in state is known as an event.

8.1.1 Exception Handling

Each type of possible exception in a system is assigned a unique nonnegative

integer exception number. Some of these numbers are assigned by the designers

of the processor. Other numbers are assigned by the designers of the operating

system kernel (the memory-resident part of the operating system). Examples of

the former include divide by zero, page faults, memory access violations, breakpoints,

and arithmetic overflows. Examples of the latter include system calls and

signals from external I/O devices.

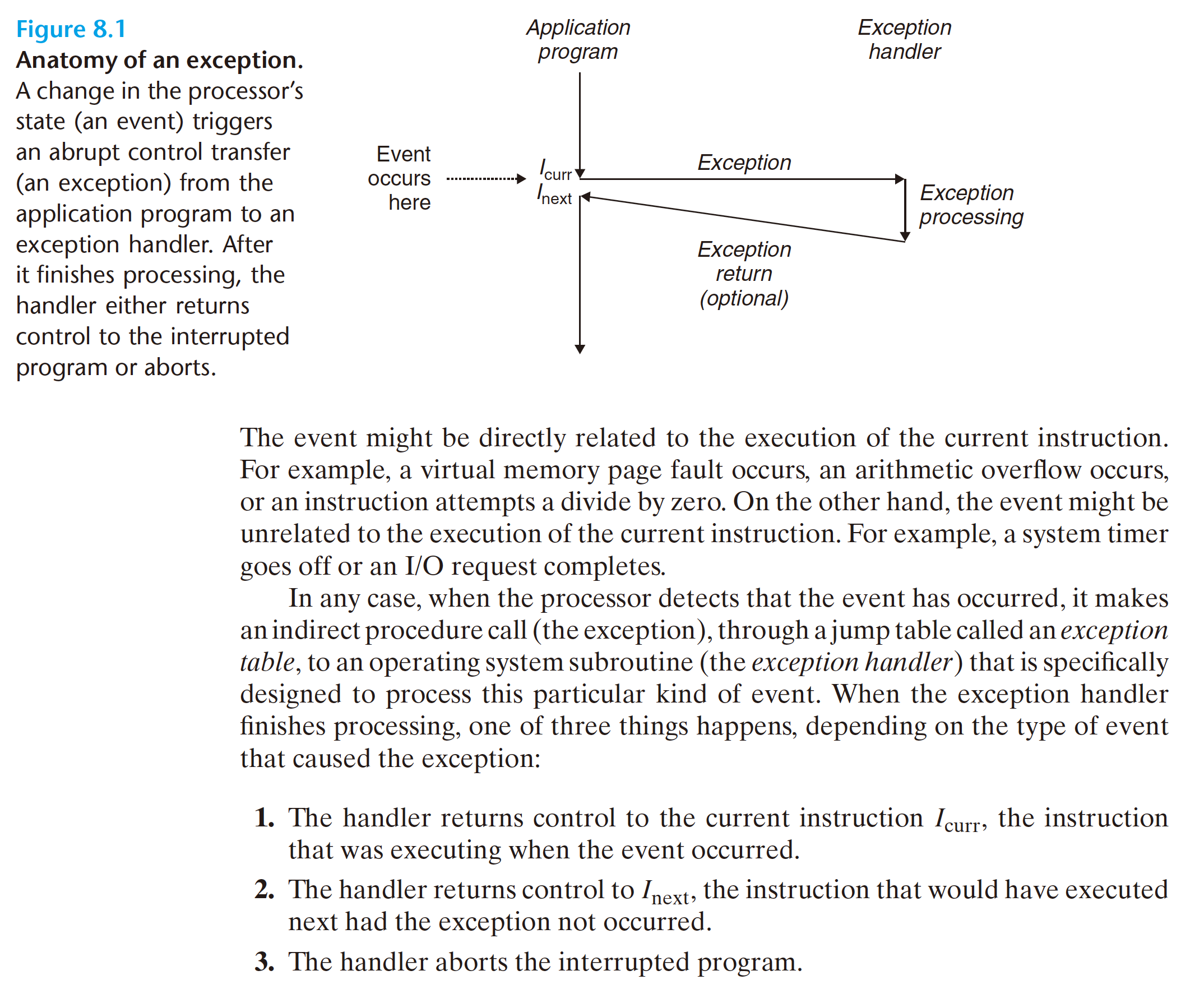

At system boot time (when the computer is reset or powered on), the operating

system allocates and initializes a jump table called an exception table, so that

entry k contains the address of the handler for exception k.

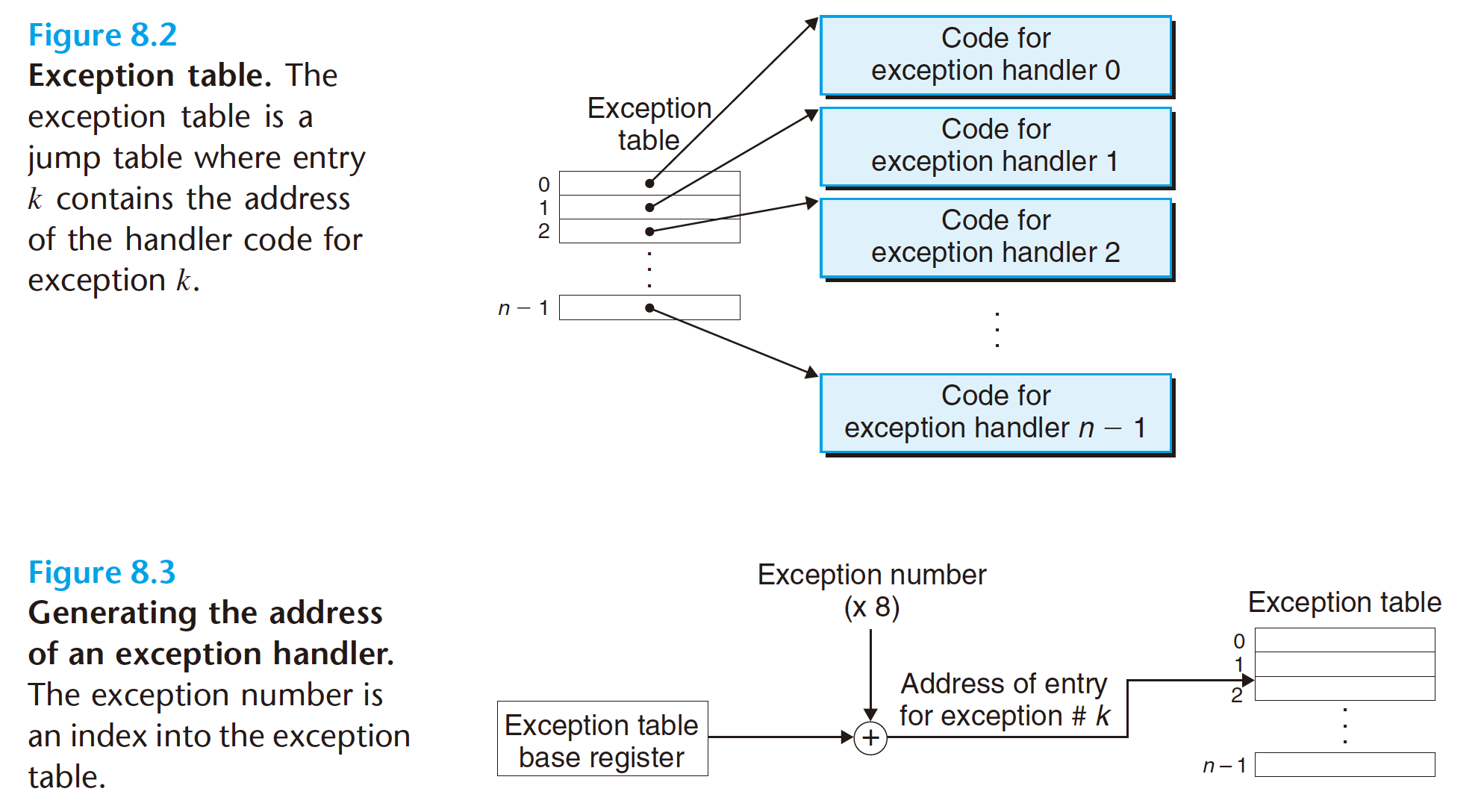

At run time (when the system is executing some program), the processor

detects that an event has occurred and determines the corresponding exception

number k. The processor then triggers the exception by making an indirect procedure

call, through entry k of the exception table, to the corresponding handler. Figure 8.3 shows how the processor uses the exception table to form the address of

the appropriate exception handler. The exception number is an index into the exception

table, whose starting address is contained in a special CPU register called

the exception table base register.

An exception is akin to a procedure call, but with some important differences:

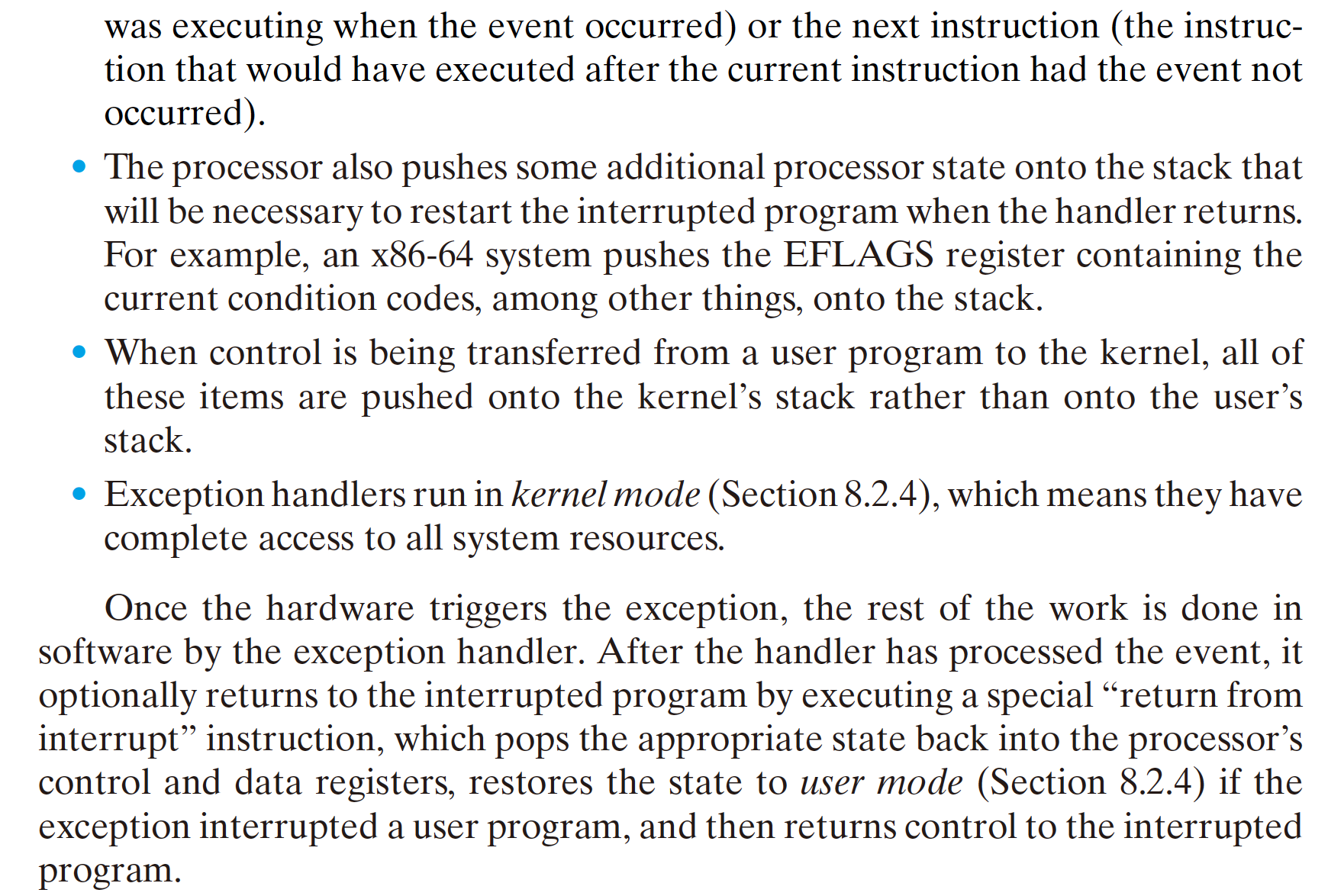

8.1.2 Classes of Excepitons

- Interrupts

After the current instruction finishes executing, the processor notices that the

interrupt pin has gone high, reads the exception number from the system bus, and

then calls the appropriate interrupt handler.When the handler returns, it returns

control to the next instruction (i.e., the instruction that would have followed the

current instruction in the control flow had the interrupt not occurred). The effect is

that the program continues executing as though the interrupt had never happened.

After the current instruction finishes executing, the processor notices that the

interrupt pin has gone high, reads the exception number from the system bus, and

then calls the appropriate interrupt handler.When the handler returns, it returns

control to the next instruction (i.e., the instruction that would have followed the

current instruction in the control flow had the interrupt not occurred). The effect is

that the program continues executing as though the interrupt had never happened. - Traps and System Calls

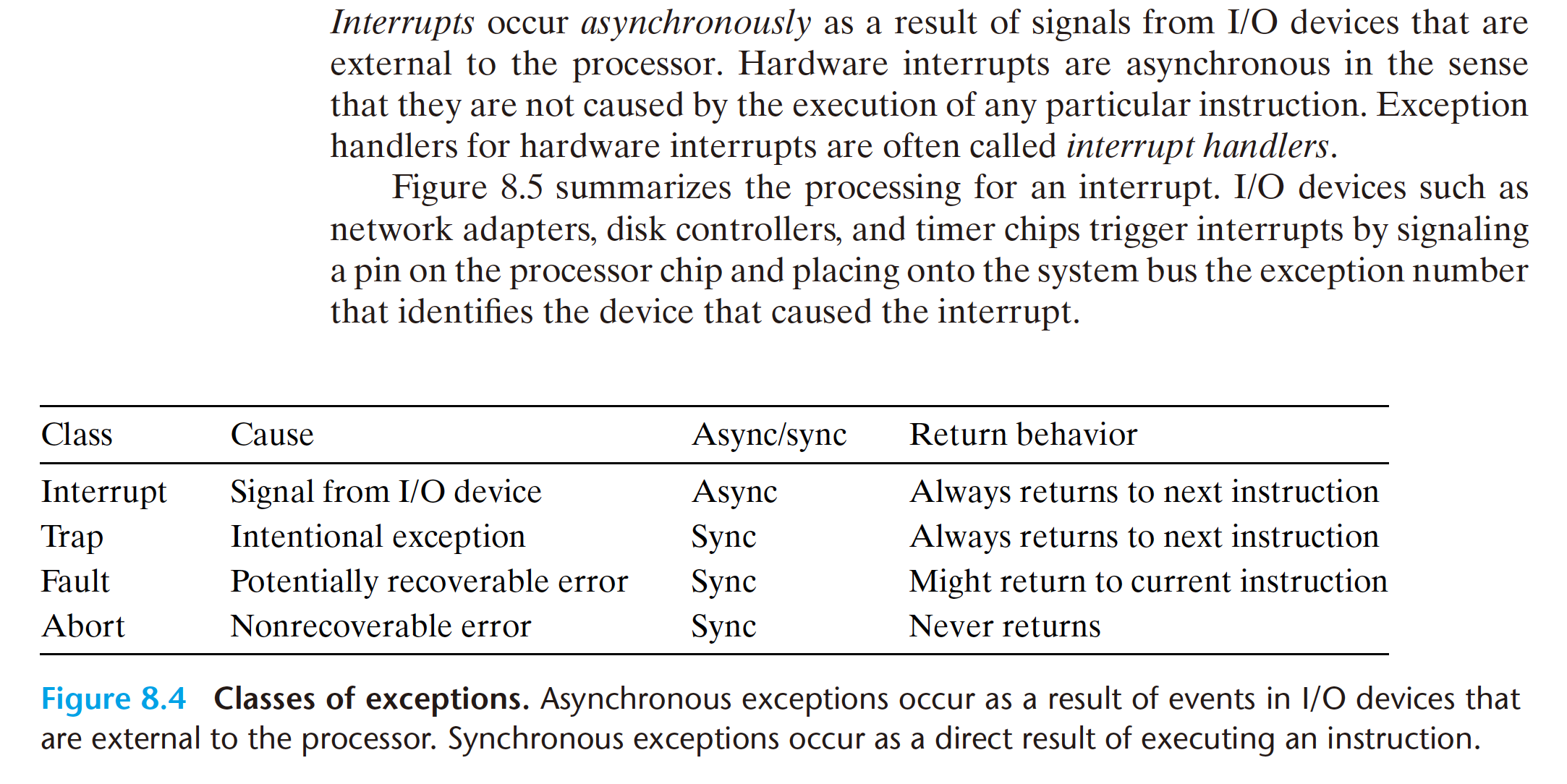

Traps are intentional exceptions that occur as a result of executing an instruction.

Like interrupt handlers, trap handlers return control to the next instruction. The

most important use of traps is to provide a procedure-like interface between user

programs and the kernel, known as a system call.

Traps are intentional exceptions that occur as a result of executing an instruction.

Like interrupt handlers, trap handlers return control to the next instruction. The

most important use of traps is to provide a procedure-like interface between user

programs and the kernel, known as a system call.

From a programmer’s perspective, a system call is identical to a regular function call. However, their implementations are quite different. Regular functions run in user mode, which restricts the types of instructions they can execute, and they access the same stack as the calling function. A system call runs in kernel mode, which allows it to execute privileged instructions and access a stack defined in the kernel. - Faults

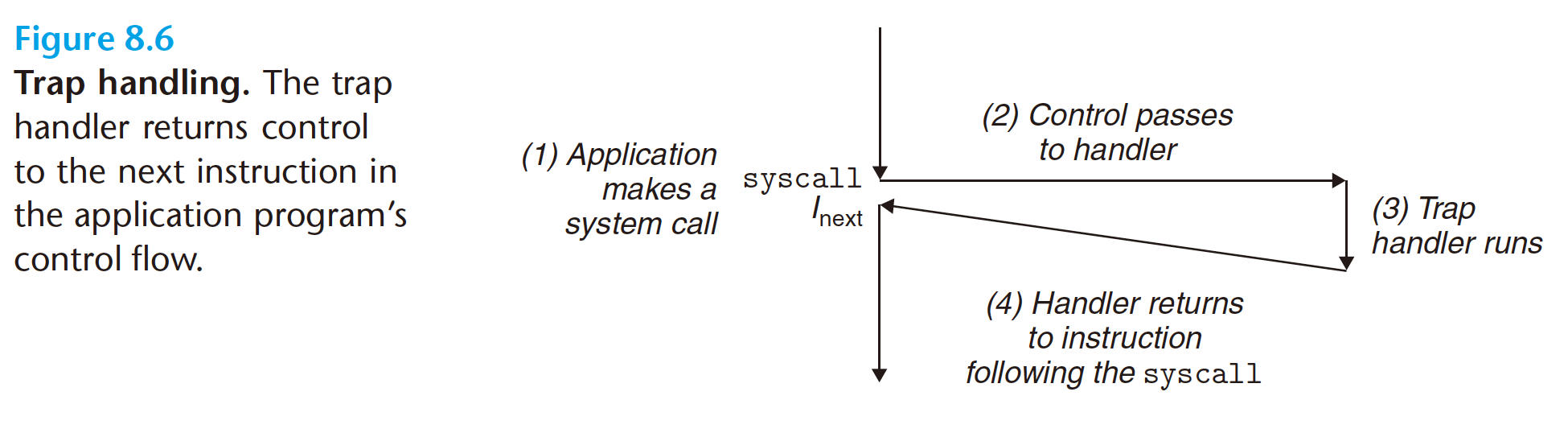

Faults result from error conditions that a handler might be able to correct.When

a fault occurs, the processor transfers control to the fault handler. If the handler

is able to correct the error condition, it returns control to the faulting instruction,

thereby re-executing it. Otherwise, the handler returns to an

Faults result from error conditions that a handler might be able to correct.When

a fault occurs, the processor transfers control to the fault handler. If the handler

is able to correct the error condition, it returns control to the faulting instruction,

thereby re-executing it. Otherwise, the handler returns to an abortroutine in the kernel that terminates the application program that caused the fault. Figure 8.7 summarizes the processing for a fault.

A classic example of a fault is the page fault exception, which occurs when an instruction references a virtual address whose corresponding page is not resident in memory and must therefore be retrieved from disk. As we will see in Chapter 9, a page is a contiguous block (typically 4 KB) of virtual memory. The page fault handler loads the appropriate page from disk and then returns control to the instruction that caused the fault. When the instruction executes again, the appropriate page is now resident in memory and the instruction is able to run to completion without faulting. - Aborts

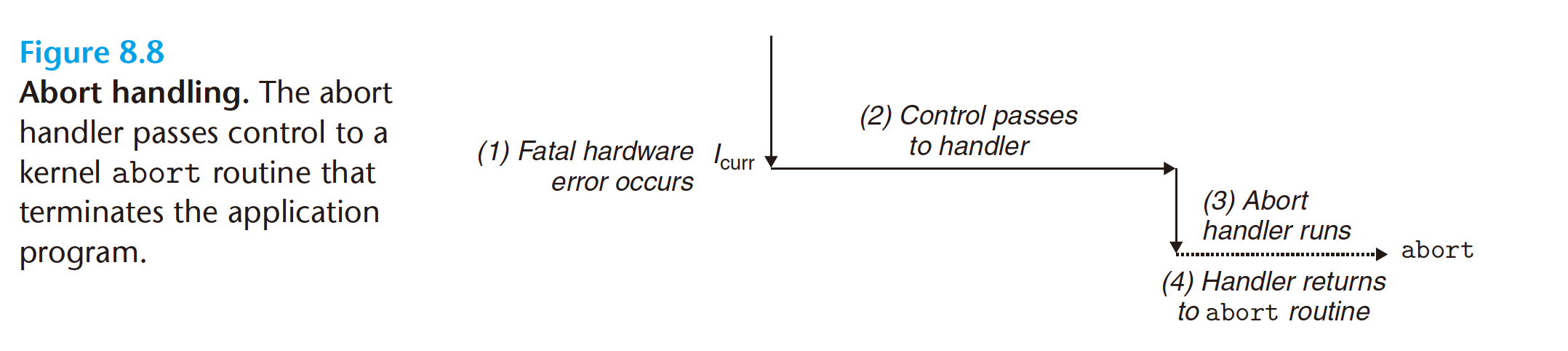

Aborts result from unrecoverable fatal errors, typically hardware errors such

as parity errors that occur when DRAM or SRAM bits are corrupted. Abort

handlers never return control to the application program. As shown in Figure 8.8,

the handler returns control to an

Aborts result from unrecoverable fatal errors, typically hardware errors such

as parity errors that occur when DRAM or SRAM bits are corrupted. Abort

handlers never return control to the application program. As shown in Figure 8.8,

the handler returns control to an abortroutine that terminates the application program.

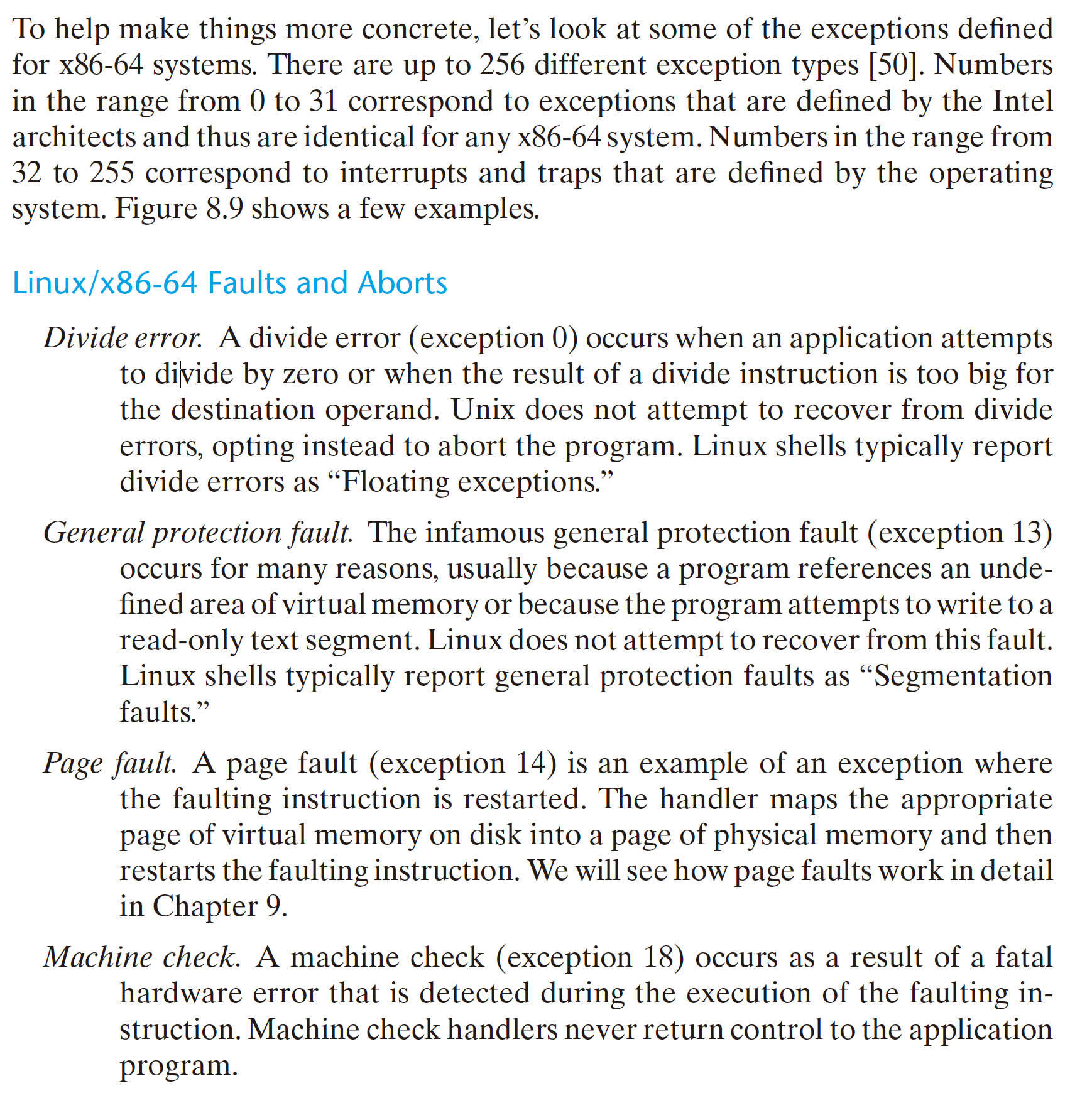

8.1.3 Exceptions in Linux/x86-64 systems

8.2 Processes

Exceptions are the basic building blocks that allow the operating system kernel

to provide the notion of a process, one of the most profound and successful ideas

in computer science.

When we run a program on a modern system, we are presented with the

illusion that our program is the only one currently running in the system. Our

program appears to have exclusive use of both the processor and the memory.

The processor appears to execute the instructions in our program, one after the

other, without interruption. Finally, the code and data of our program appear to

be the only objects in the system’s memory. These illusions are provided to us by

the notion of a process.

The classic definition of a process is an instance of a program in execution.

Each program in the system runs in the context of some process. The context

consists of the state that the program needs to run correctly. This state includes the

program’s code and data stored in memory, its stack, the contents of its generalpurpose

registers, its program counter, environment variables, and the set of open

file descriptors.

- An independent logical control flow that provides the illusion that our program has exclusive use of the processor.

- A private address space that provides the illusion that our program has exclusive use of the memory system.

8.2.1 Logical Control Flow

If we were to use a debugger to single-step the execution of our program, we would observe a series of program counter (PC) values that corresponded exclusively to instructions contained in our program’s executable object file or in shared objects linked into our program dynamically at run time. This sequence of PC values is known as a logical control flow, or simply logical flow.

8.2.2 Concurrent Flows

The general phenomenon of multiple flows executing concurrently is known as concurrency. The notion of a process taking turns with other processes is also known as multitasking.Each time period that a process executes a portion of its flow is called a time slice. Thus, multitasking is also referred to as time slicing.

If two flows are running concurrently on different processor cores or computers, then we say that they are parallel flows, that they are running in parallel, and have parallel execution.

8.2.3 Private Address Space

A process provides each program with its own private address space. This space is private in the sense that a byte of memory associated with a particular address in the space cannot in general be read or written by any other process.

8.2.4 User and Kernel Modes

Processors typically provide this capability with a mode bit in some control

register that characterizes the privileges that the process currently enjoys. When

the mode bit is set, the process is running in kernel mode (sometimes called

supervisor mode). A process running in kernel mode can execute any instruction

in the instruction set and access any memory location in the system.

When the mode bit is not set, the process is running in user mode. A process

in user mode is not allowed to execute privileged instructions that do things such

as halt the processor, change the mode bit, or initiate an I/O operation. Nor is it

allowed to directly reference code or data in the kernel area of the address space.

8.2.5 Context Switches

The operating system kernel implements multitasking using a higher-level form of exceptional control flow known as a context switch.

The kernel maintains a context for each process. The context is the state

that the kernel needs to restart a preempted process. It consists of the values

of objects such as the general-purpose registers, the floating-point registers, the

program counter, user’s stack, status registers, kernel’s stack, and various kernel

data structures such as a page table that characterizes the address space, a process

table that contains information about the current process, and a file table that

contains information about the files that the process has opened.

At certain points during the execution of a process, the kernel can decide

to preempt the current process and restart a previously preempted process. This

decision is known as scheduling and is handled by code in the kernel, called the

scheduler. When the kernel selects a new process to run, we say that the kernel

has scheduled that process. After the kernel has scheduled a new process to run,

it preempts the current process and transfers control to the new process using a

mechanism called a context switch that

- saves the context of the current process,

- restores the saved context of some previously preempted process, and

- passes control to this newly restored process.

8.4 Process Control

8.4.1 Obtaining Process IDs

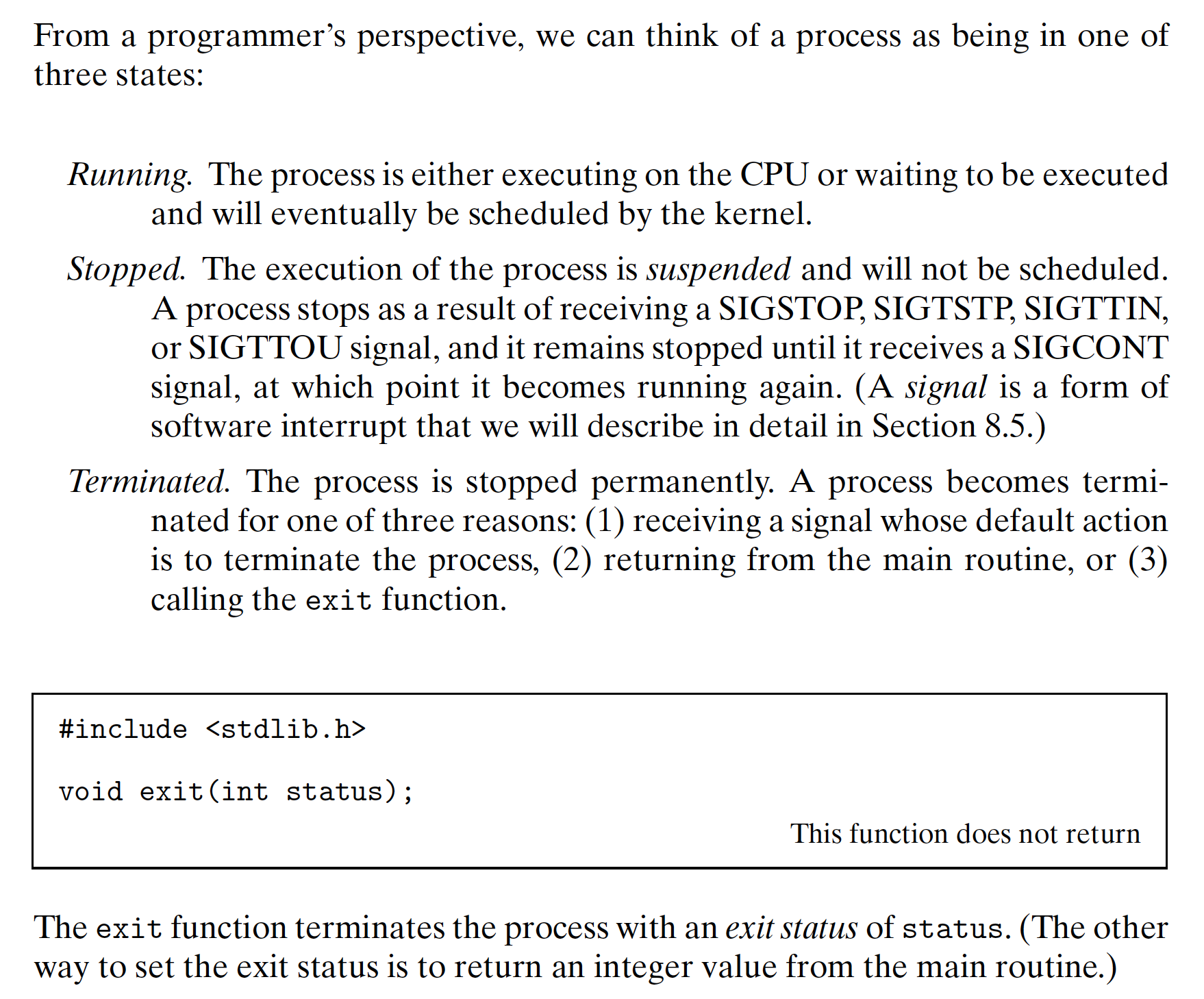

8.4.2 Creating and Terminating Processes

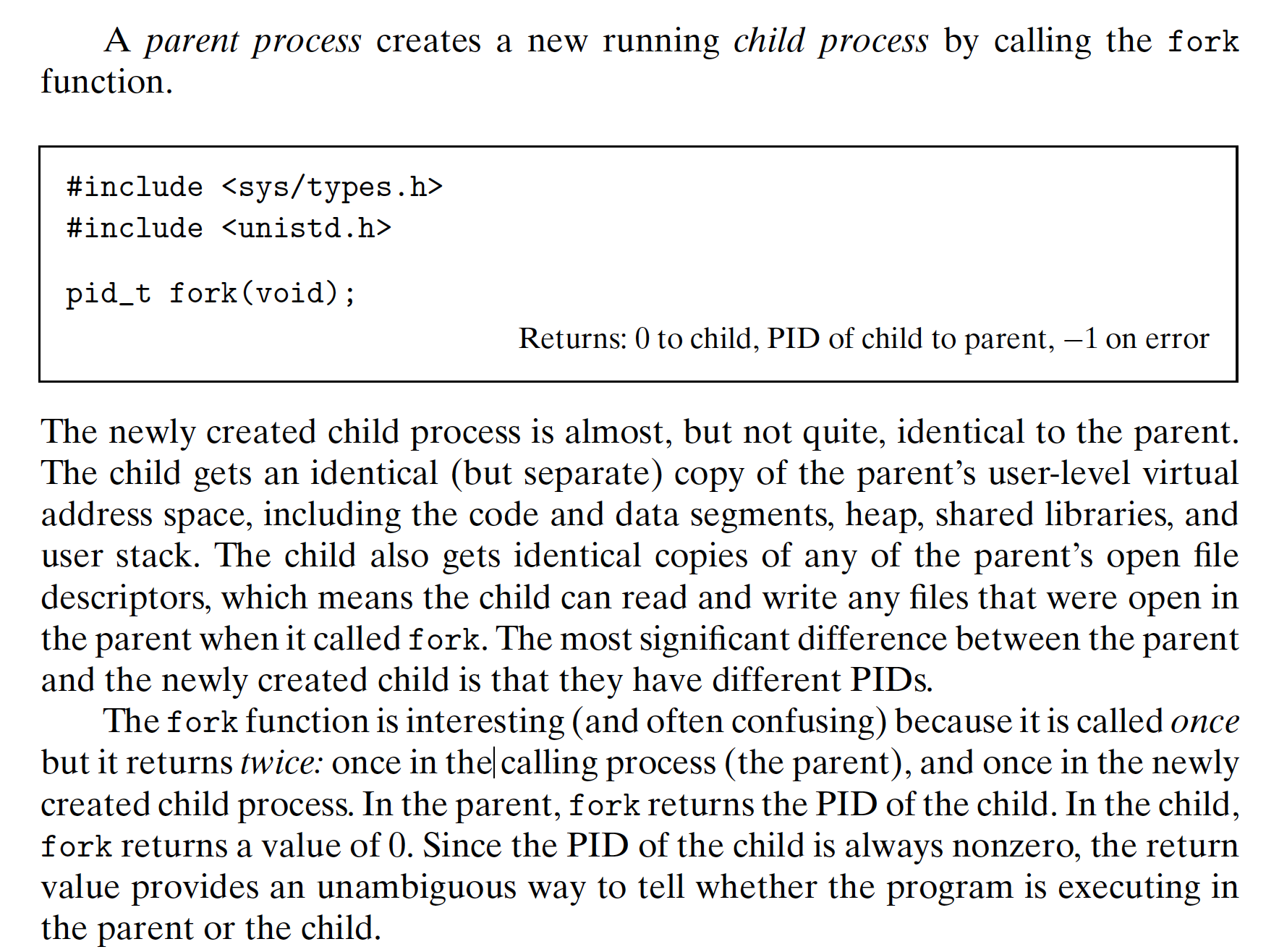

There are some subtle aspects to this simple example.

- Call once, return twice. The

forkfunction is called once by the parent, but it returns twice: once to the parent and once to the newly created child. This is fairly straightforward for programs that create a single child. But programs with multiple instances offorkcan be confusing and need to be reasoned about carefully. - Concurrent execution. The parent and the child are separate processes that

run concurrently. The instructions in their logical control flows can be interleaved by the kernel in an arbitrary way. When we run the program on our system, the parent process completes its

printfstatement first, followed by the child. However, on another system the reverse might be true. In general, as programmers we can never make assumptions about the interleaving of the instructions in different processes. - Duplicate but separate address spaces. If we could halt both the parent and the

child immediately after the

forkfunction returned in each process, we would see that the address space of each process is identical. Each process has the same user stack, the same local variable values, the same heap, the same global variable values, and the same code. Thus, in our example program, local variablexhas a value of 1 in both the parent and the child when theforkfunction returns in line 6. However, since the parent and the child are separate processes, they each have their own private address spaces. Any subsequent changes that a parent or child makes toxare private and are not reflected in the memory of the other process. This is why the variablexhas different values in the parent and child when they call their respectiveprintfstatements. - Shared files. When we run the example program, we notice that both parent and child print their output on the screen. The reason is that the child inherits all of the parent’s open files. When the parent calls fork, the

stdoutfile is open and directed to the screen. The child inherits this file, and thus its output is also directed to the screen.

8.4.3 Reaping Child Processes

When a process terminates for any reason, the kernel does not remove it from

the system immediately. Instead, the process is kept around in a terminated state

until it is reaped by its parent. When the parent reaps the terminated child, the

kernel passes the child’s exit status to the parent and then discards the terminated

process, at which point it ceases to exist. A terminated process that has not yet

been reaped is called a zombie.

When a parent process terminates, the kernel arranges for the init process to become the adopted parent of any orphaned children. The init process, which has a PID of 1, is created by the kernel during system start-up, never terminates, and is the ancestor of every process. If a parent process terminates without reaping its zombie children, then the kernel arranges for the init process to reap them. However, long-running programs such as shells or servers should always reap their zombie children. Even though zombies are not running, they still consume system memory resources.

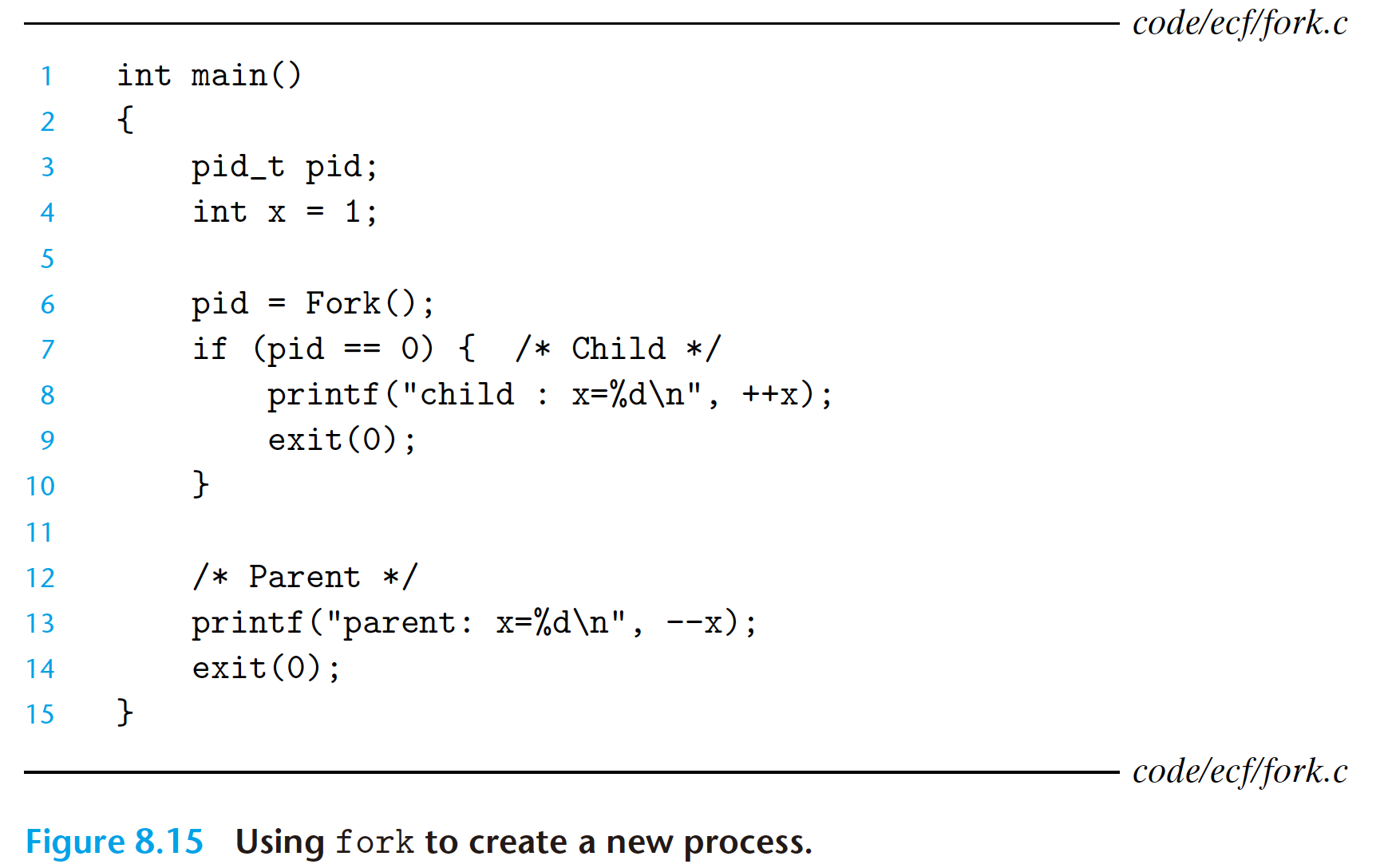

The waitpid function is complicated. By default (when options = 0),

waitpid suspends execution of the calling process until a child process in its wait

set terminates. If a process in the wait set has already terminated at the time of the

call, then waitpid returns immediately. In either case, waitpid returns the PID of

the terminated child that caused waitpid to return. At this point, the terminated

child has been reaped and the kernel removes all traces of it from the system.

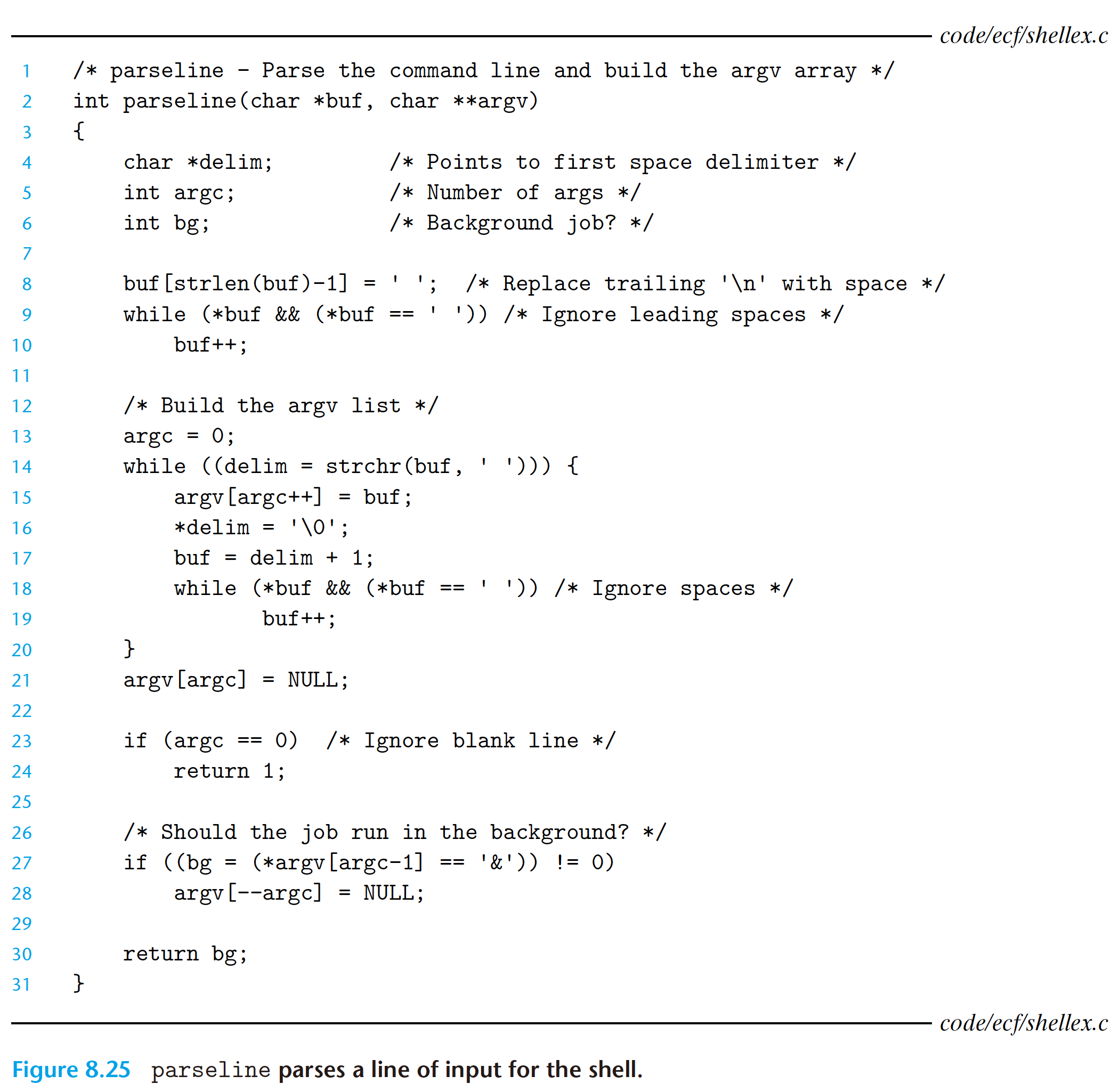

8.4.5 Loading and Running Programs

8.4.6 Using fork and execve to Run Programs

8.5 Signals

In this section, we will study a higher-level software form of exceptional control flow, known as a Linux signal, that allows processes and the kernel to interrupt other processes.

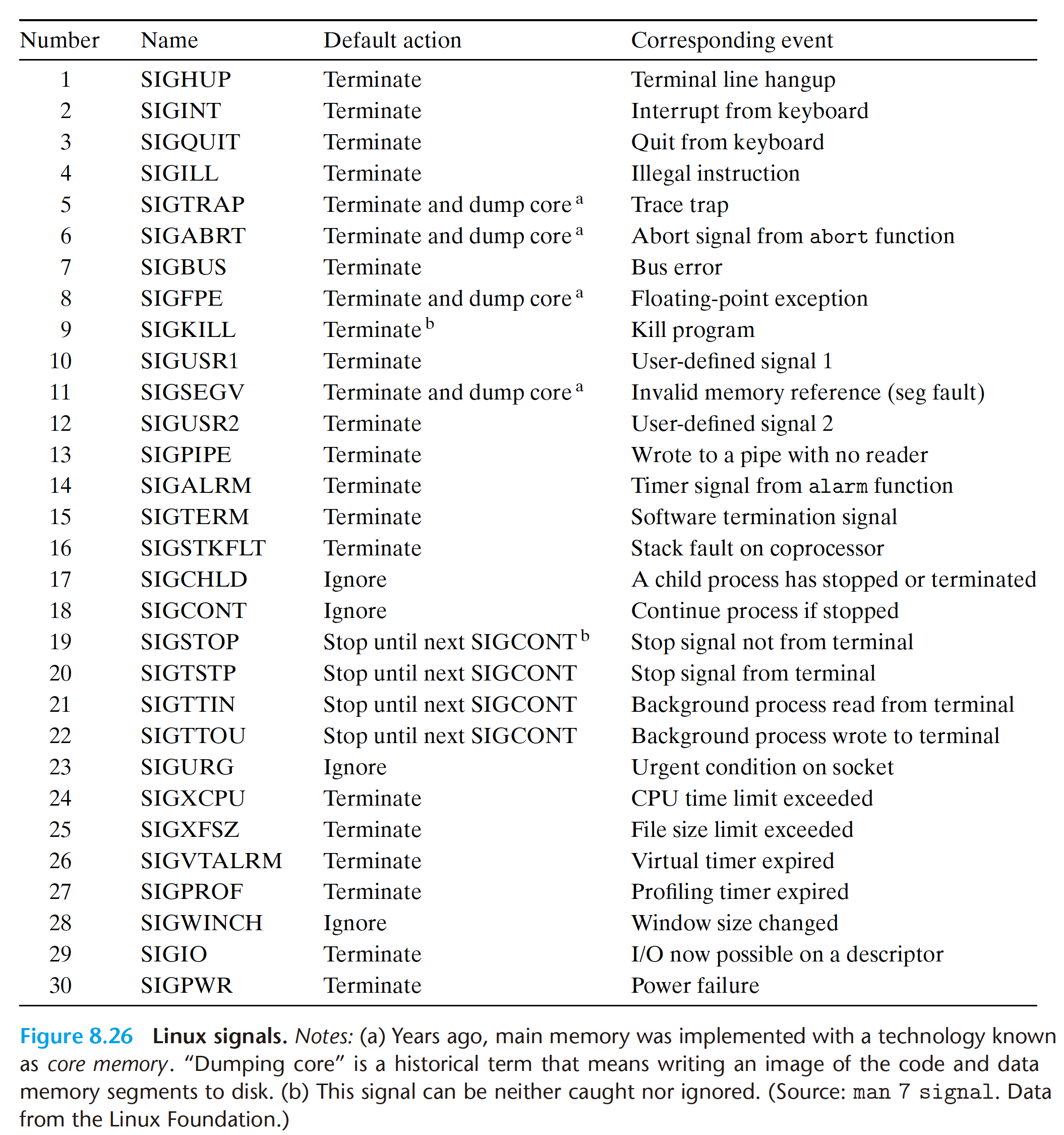

A signal is a small message that notifies a process that an event of some type has occurred in the system. Each signal type corresponds to some kind of system event. Low-level hardware exceptions are processed by the kernel’s exception handlers and would not normally be visible to user processes. Signals provide a mechanism for exposing the occurrence of such exceptions to user processes. For example, if a process attempts to divide by zero, then the kernel sends it a SIGFPE signal (number 8). If a process executes an illegal instruction, the kernel sends it a SIGILL signal (number 4). If a process makes an illegal memory reference, the kernel sends it a SIGSEGV signal (number 11). Other signals correspond to higher-level software events in the kernel or in other user processes. For example, if you type Ctrl+C (i.e., press the Ctrl key and the ‘c’ key at the same time) while a process is running in the foreground, then the kernel sends a SIGINT (number 2) to each process in the foreground process group. A process can forcibly terminate another process by sending it a SIGKILL signal (number 9). When a child process terminates or stops, the kernel sends a SIGCHLD signal (number 17) to the parent.

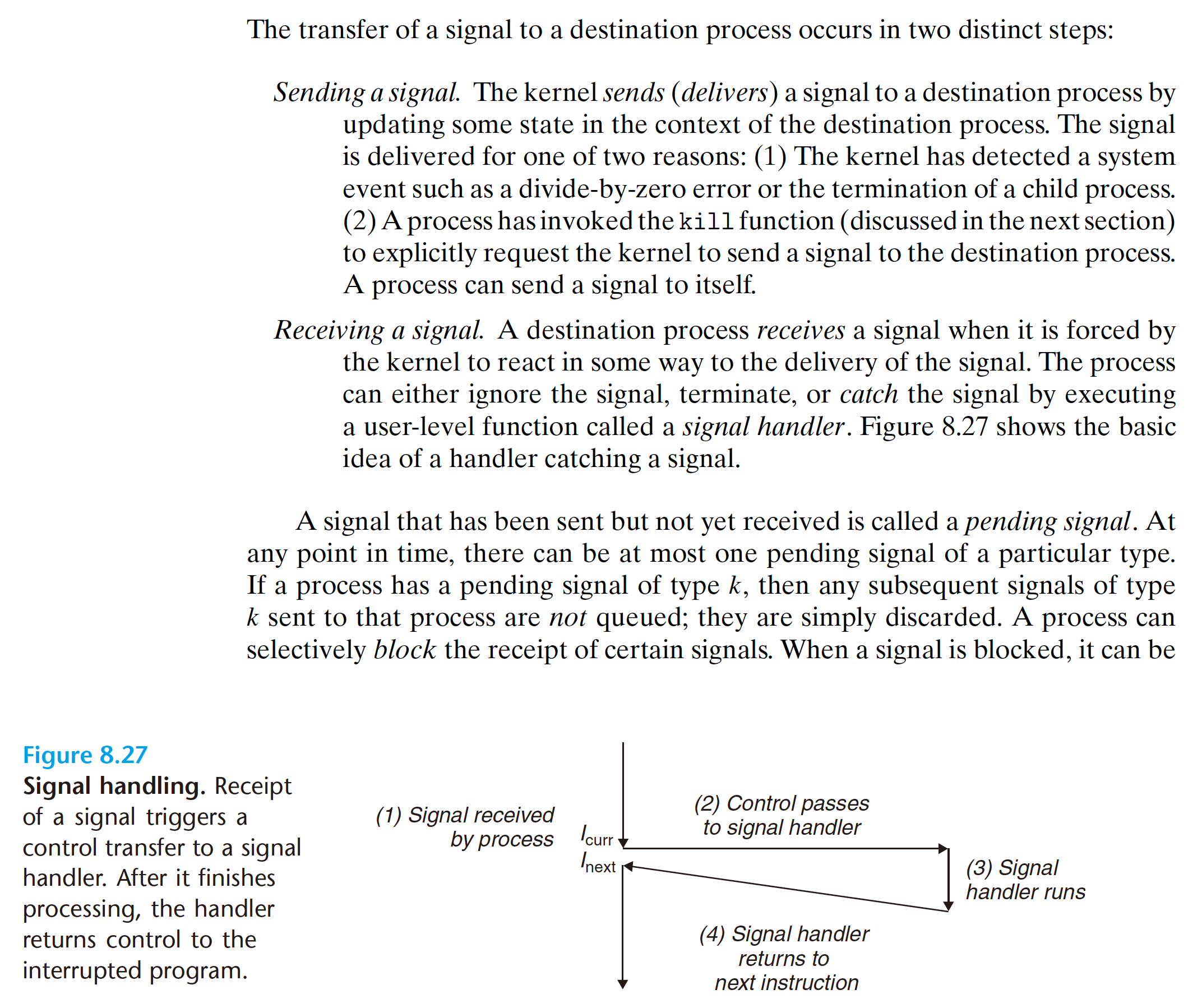

8.5.1 Signal Terminology

A pending signal is received at most once. For each process, the kernel maintains

the set of pending signals in the pending bit vector, and the set of blocked

signals in the blocked bit vector. The kernel sets bit k in pending whenever a

signal of type k is delivered and clears bit k in pending whenever a signal of type

k is received.

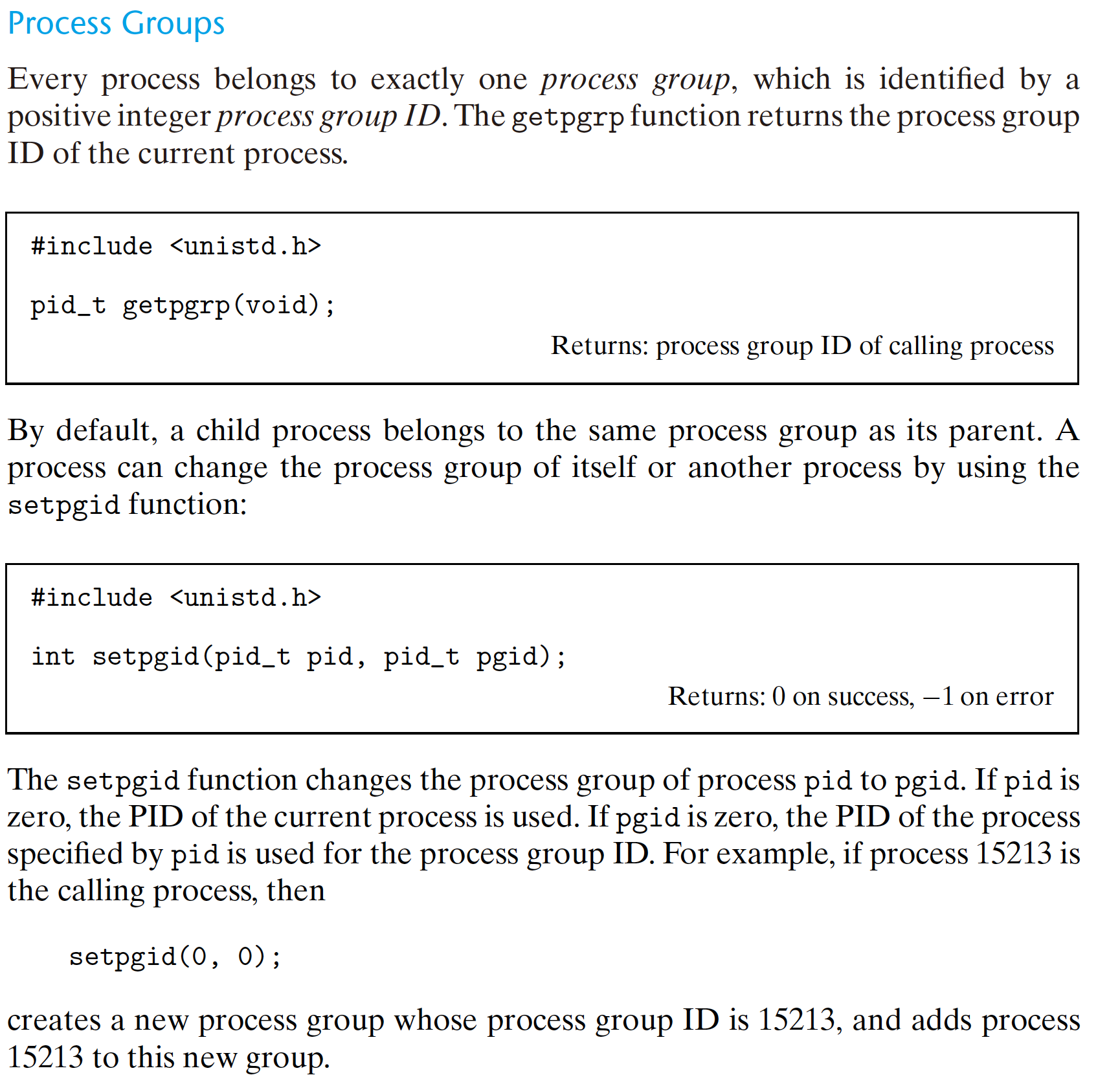

8.5.2 Sending Signals

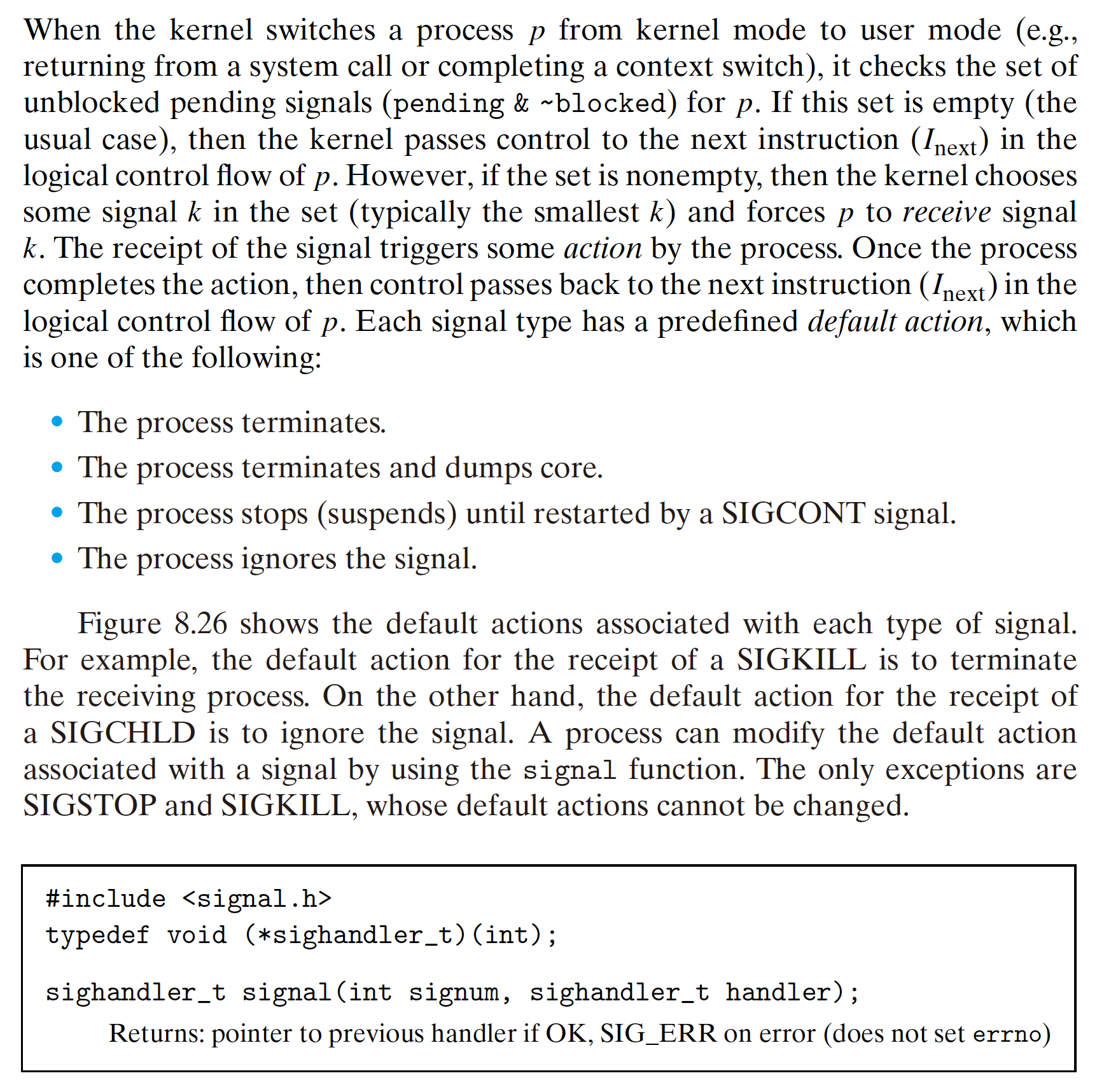

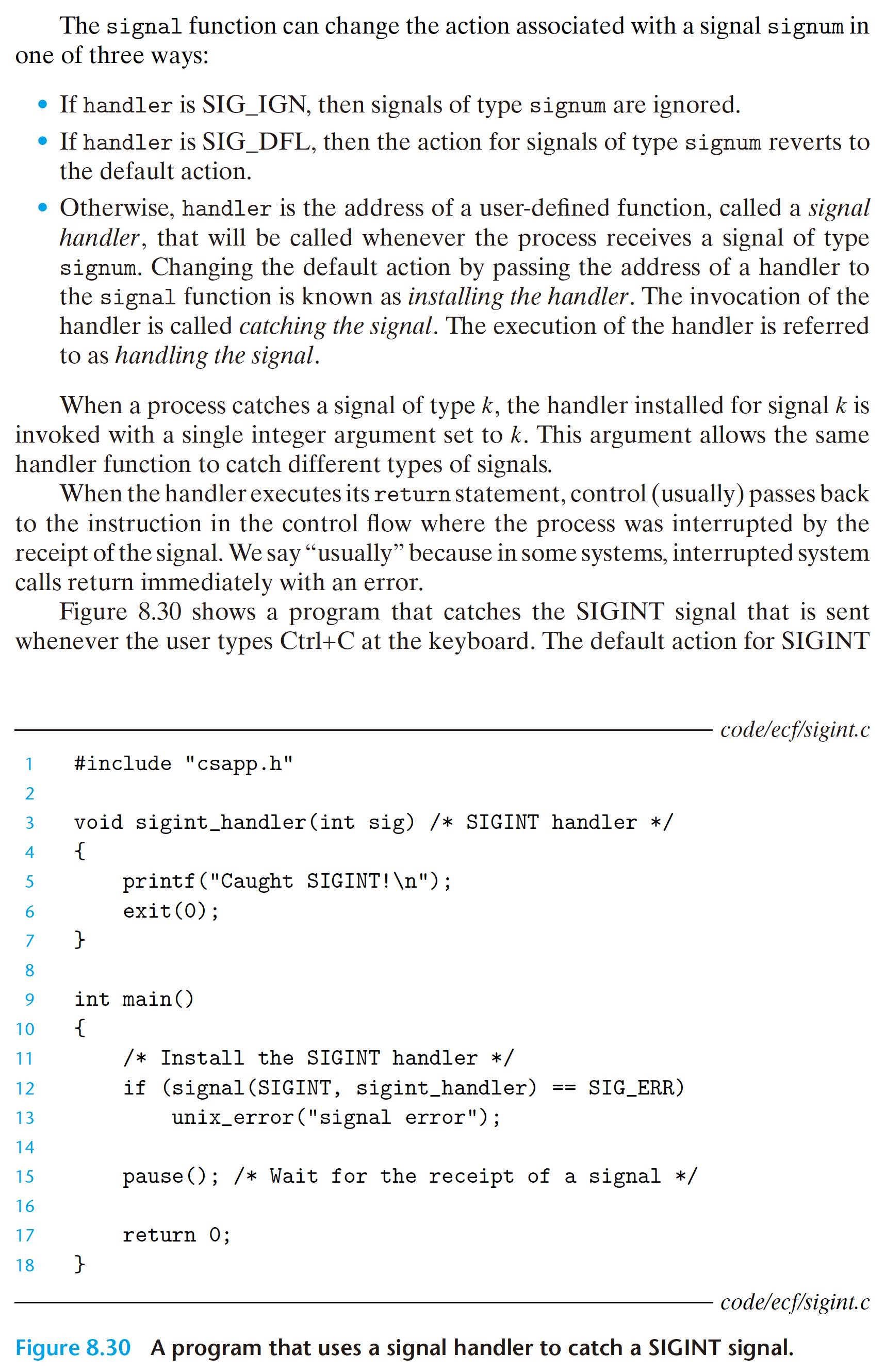

8.5.3 Receiving Signals

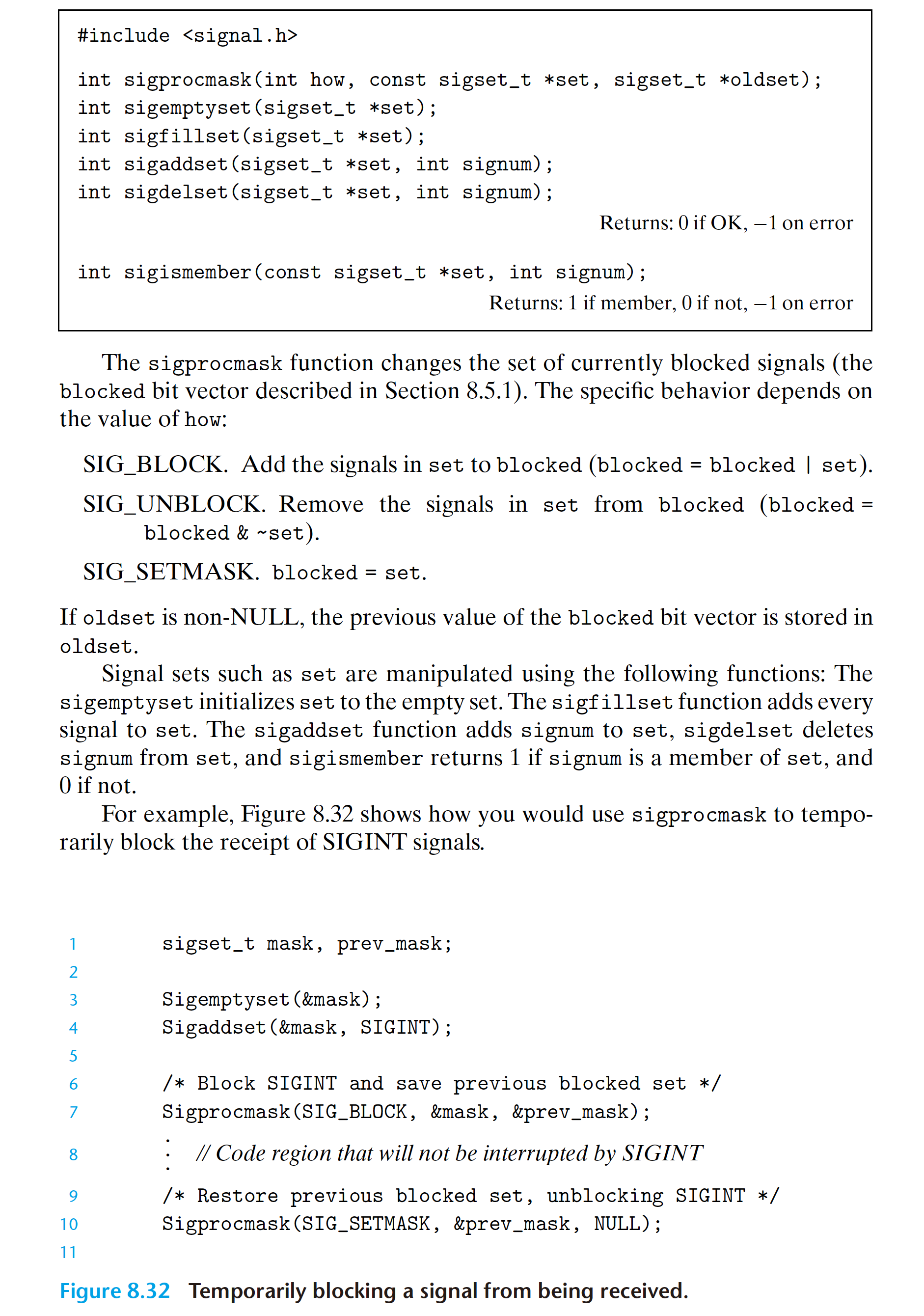

8.5.4 Blocking and Unblocking Signals

8.5.5 Writing Signal Handlers