Chapter 3 Machine-Level Representation of Programs

3.4 accessing informaition

3.5 Arithmetic and Logical Operations

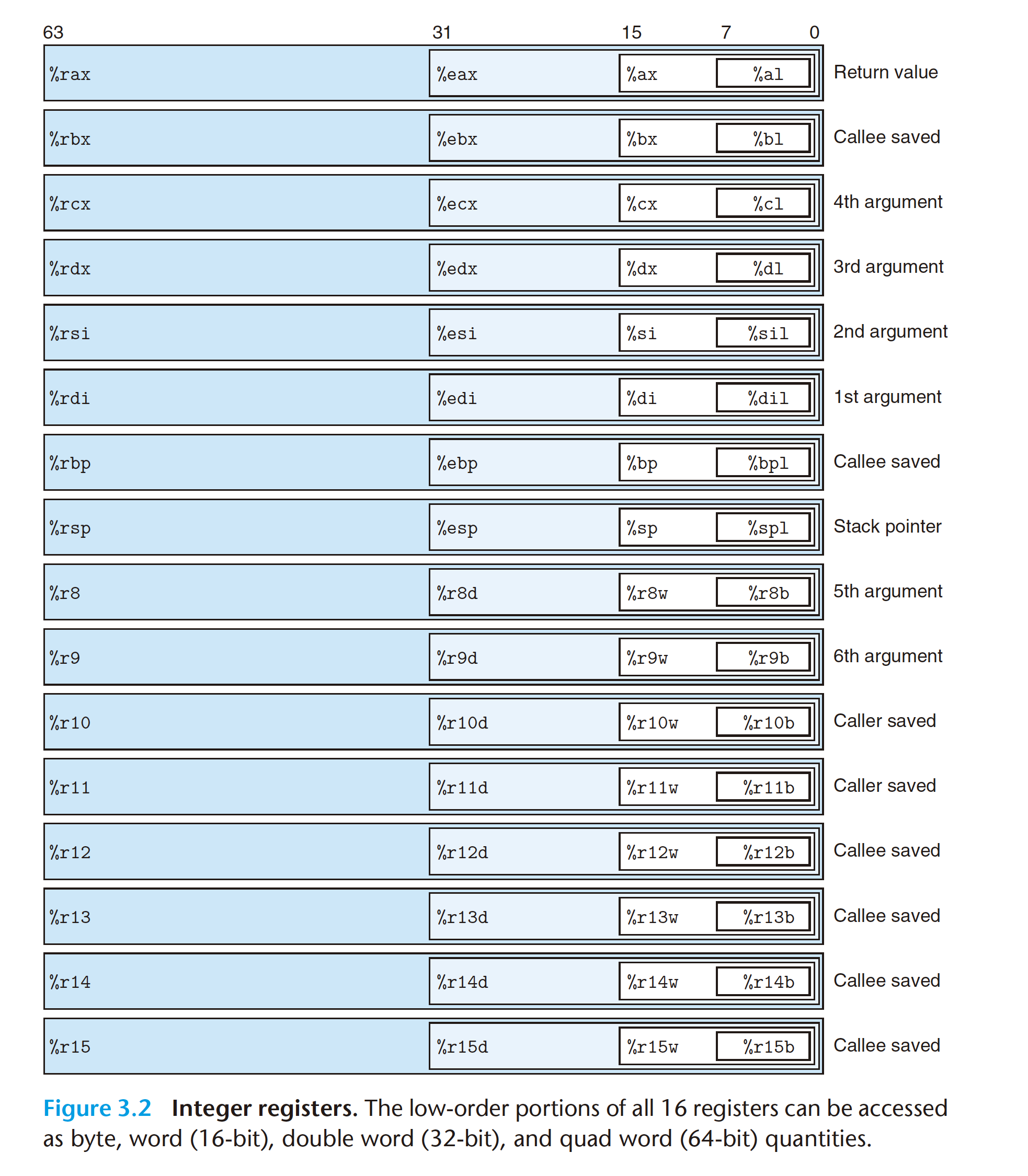

Naming convention: word(2 bytes), double word(4 bytes), quad word(8 bytes)

3.6 Control

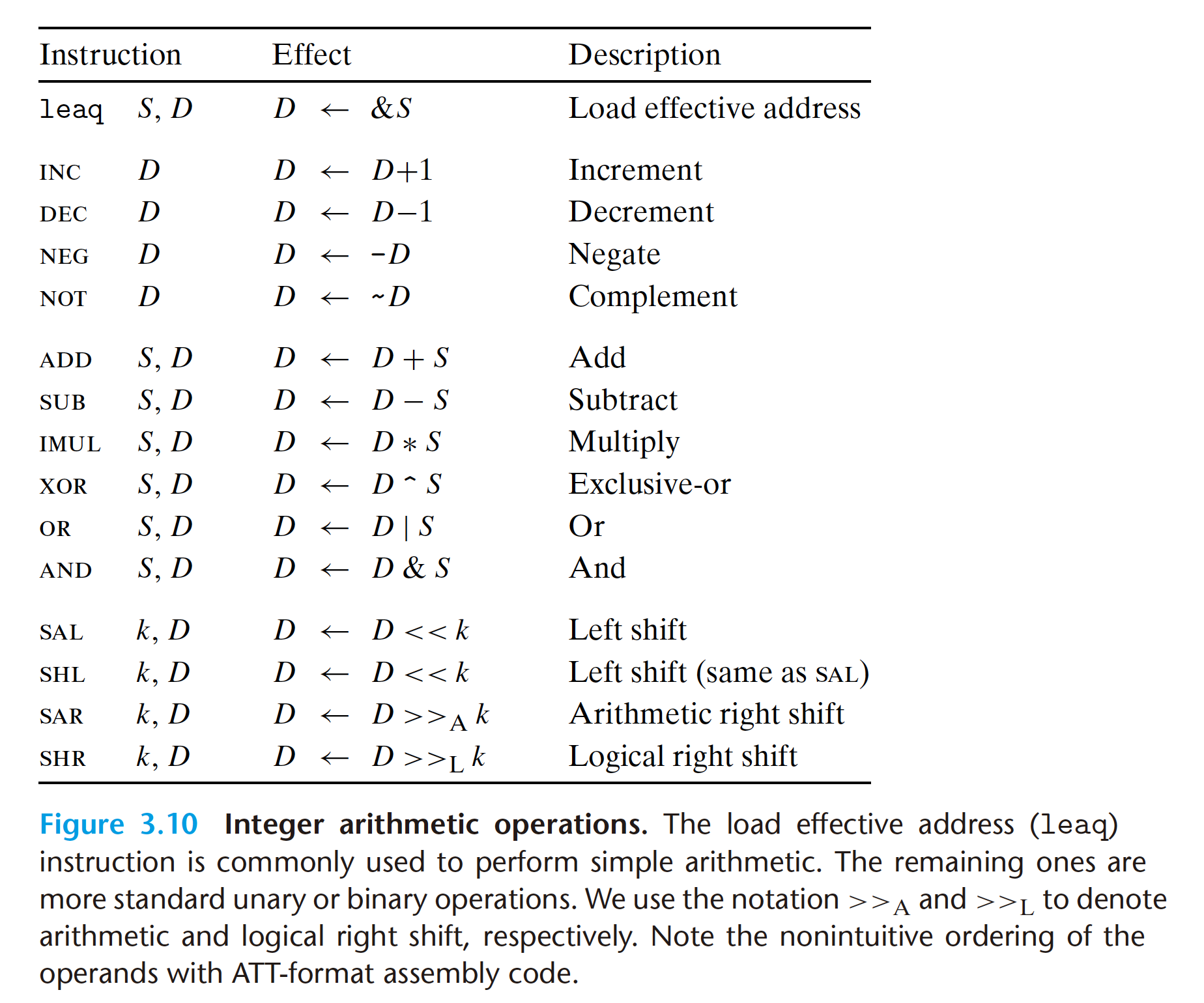

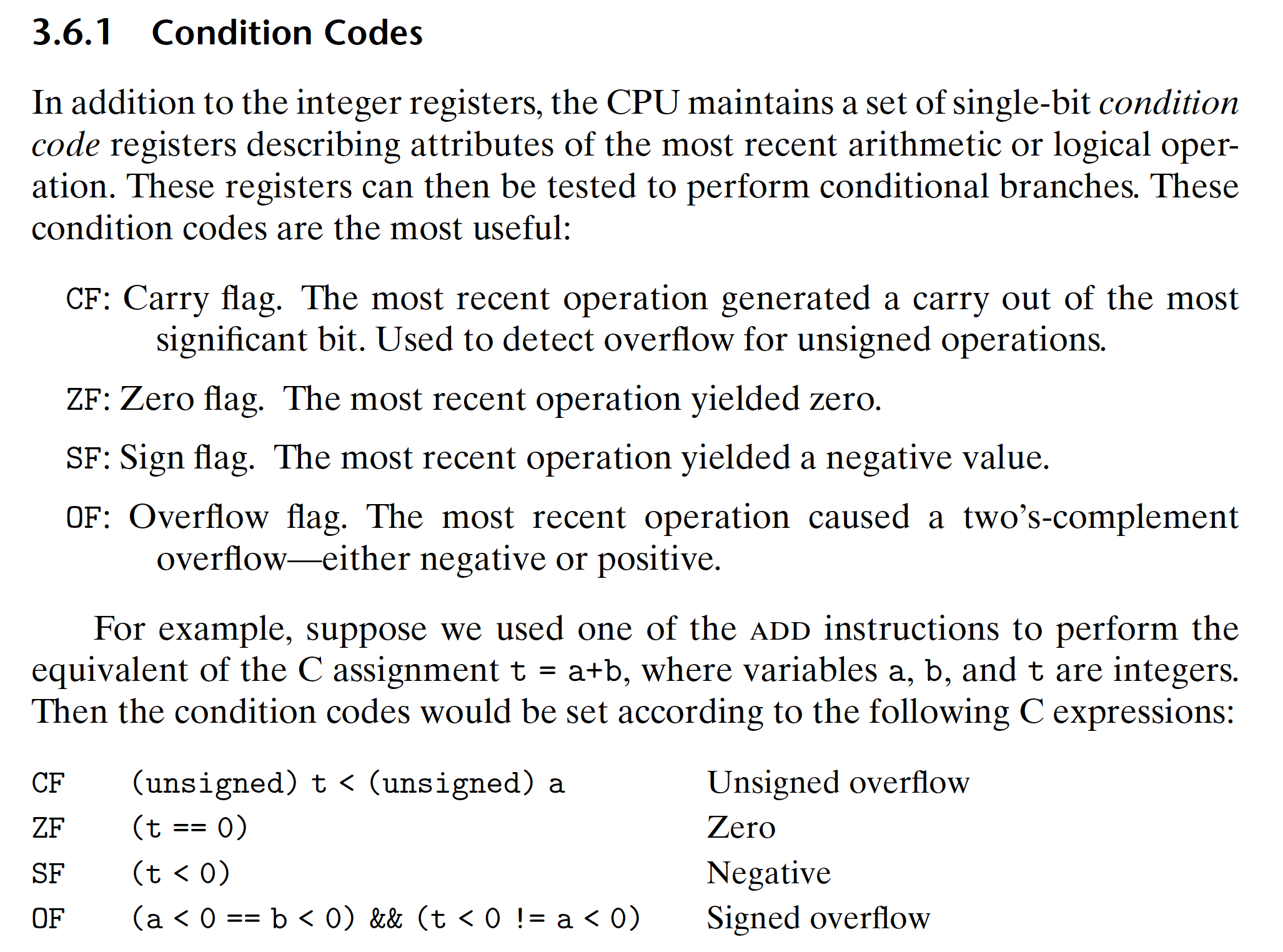

The leaq instruction does not alter any condition codes, since it is intended

to be used in address computations. Otherwise, all of the instructions listed in

Figure 3.10 cause the condition codes to be set. For the logical operations, such

as xor, the carry and overflow flags are set to zero. For the shift operations, the

carry flag is set to the last bit shifted out, while the overflow flag is set to zero. For

reasons that we will not delve into, the inc and dec instructions set the overflow

and zero flags, but they leave the carry flag unchanged.

The leaq instruction does not alter any condition codes, since it is intended

to be used in address computations. Otherwise, all of the instructions listed in

Figure 3.10 cause the condition codes to be set. For the logical operations, such

as xor, the carry and overflow flags are set to zero. For the shift operations, the

carry flag is set to the last bit shifted out, while the overflow flag is set to zero. For

reasons that we will not delve into, the inc and dec instructions set the overflow

and zero flags, but they leave the carry flag unchanged.

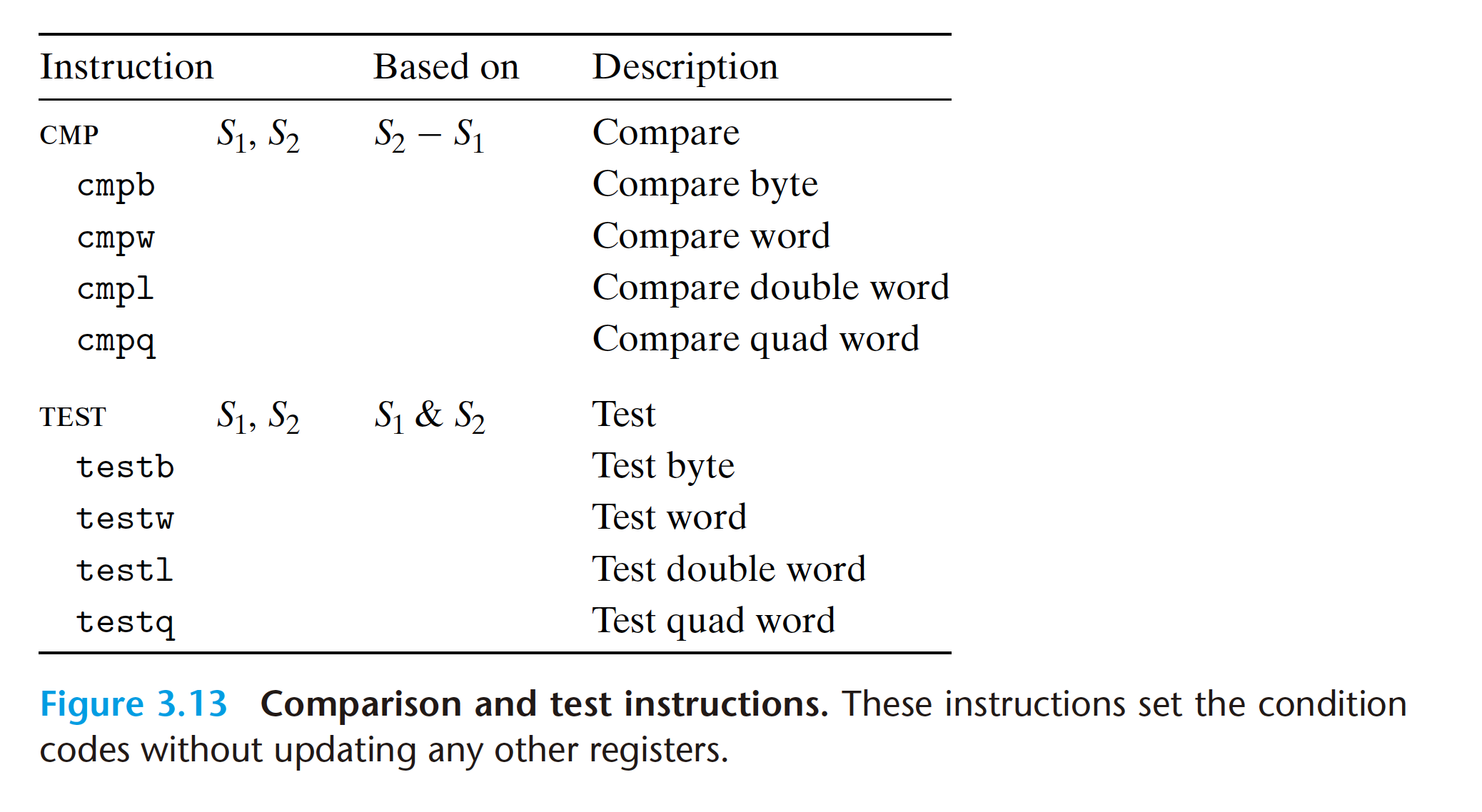

- The cmp instructions set the condition codes according to the differences of their two operands. They behave in the same way as the sub instructions, except that

- they set the condition codes without updating their destinations

The test instructions behave in the same manner as the and instructions, except that they set the condition codes without altering their destinations.

3.6.2 Accessing the Condition codes

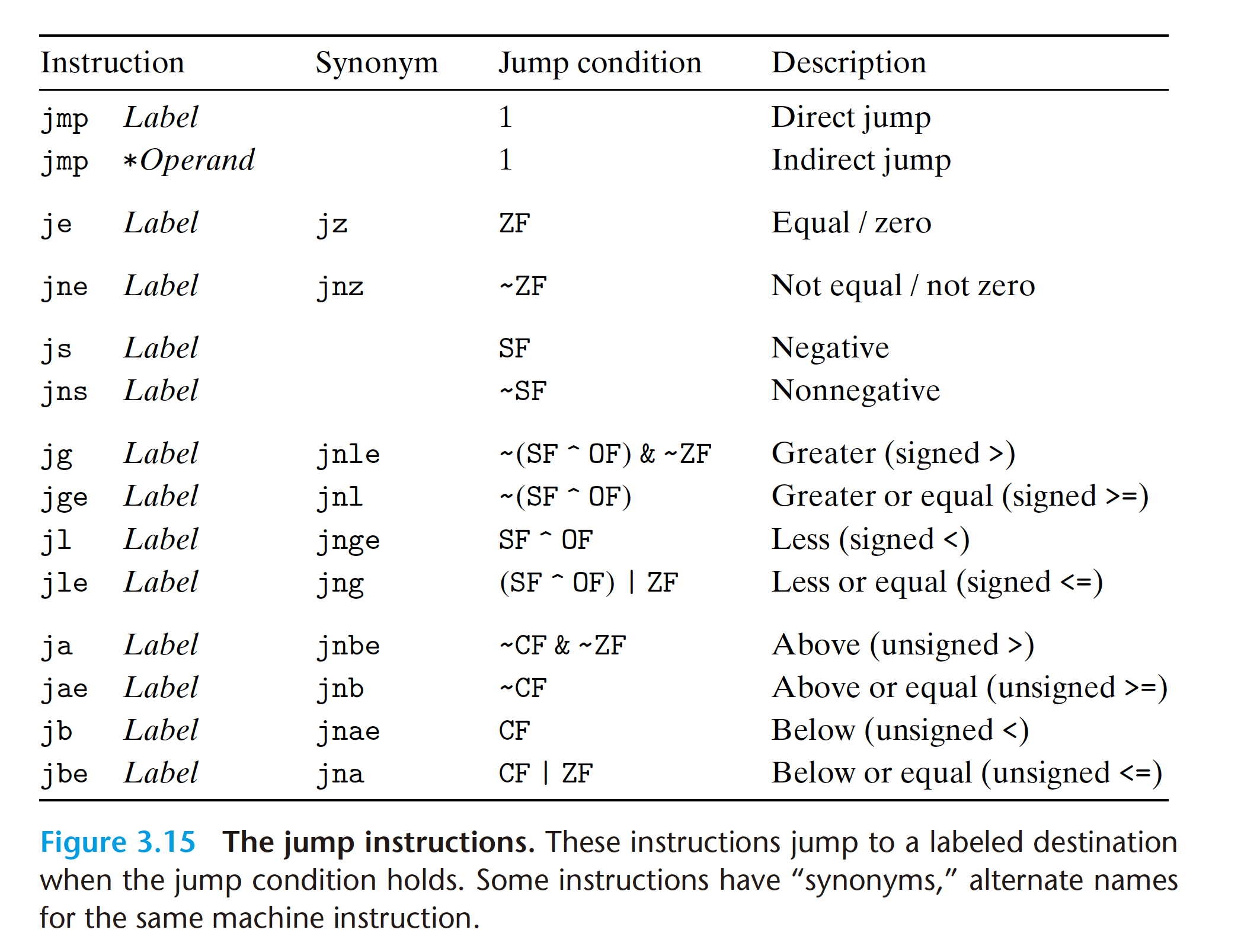

3.6.3 Jump Instrucitons

Direct jumps are written in assembly code by

giving a label as the jump target, for example, the label .L1 in the code shown.

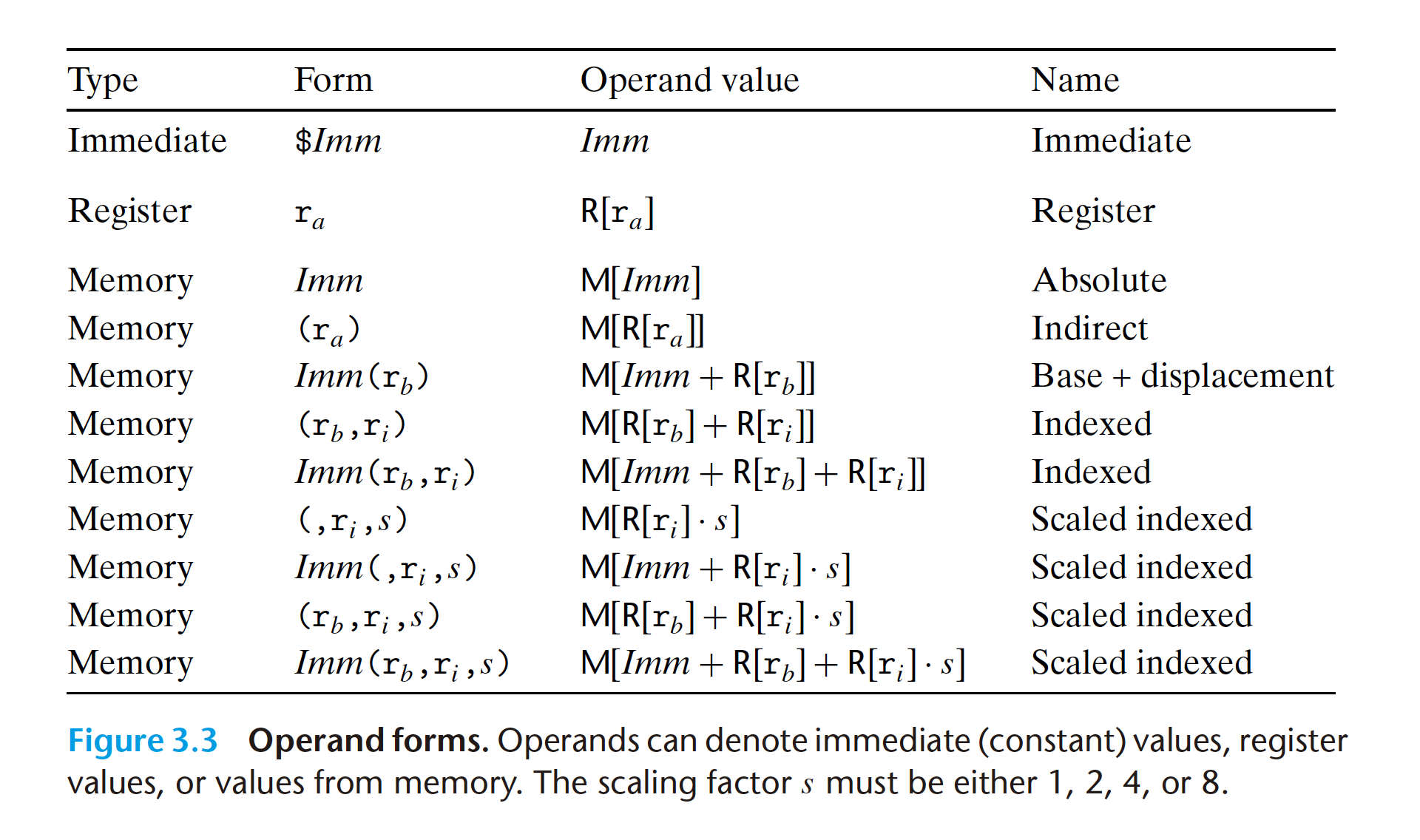

Indirect jumps are written using ‘*’ followed by an operand specifier using one of

the memory operand formats described in Figure 3.3. As examples, the instruction

Direct jumps are written in assembly code by

giving a label as the jump target, for example, the label .L1 in the code shown.

Indirect jumps are written using ‘*’ followed by an operand specifier using one of

the memory operand formats described in Figure 3.3. As examples, the instruction

jmp *%rax

uses the value in register %rax as the jump target, and the instruction

jmp *(%rax)

reads the jump target from memory, using the value in %rax as the read address

3.6.6 implementing conditional branches with conditional moves

3.6.7 Loops

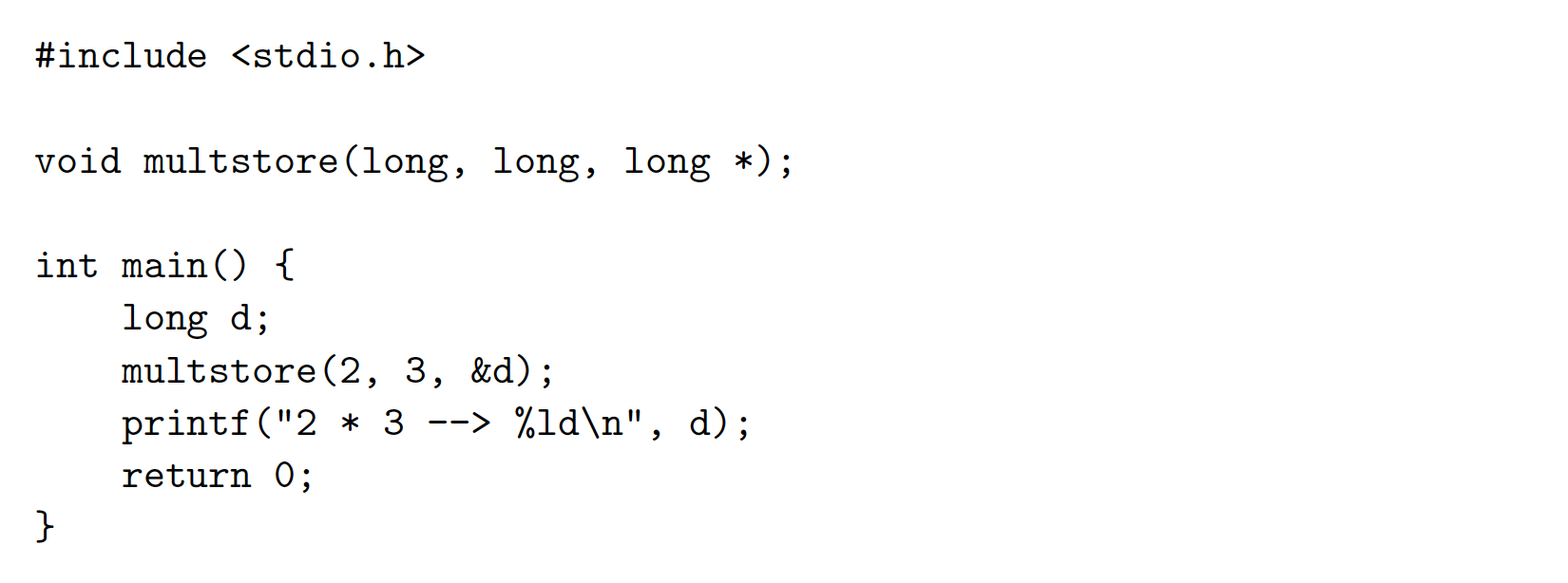

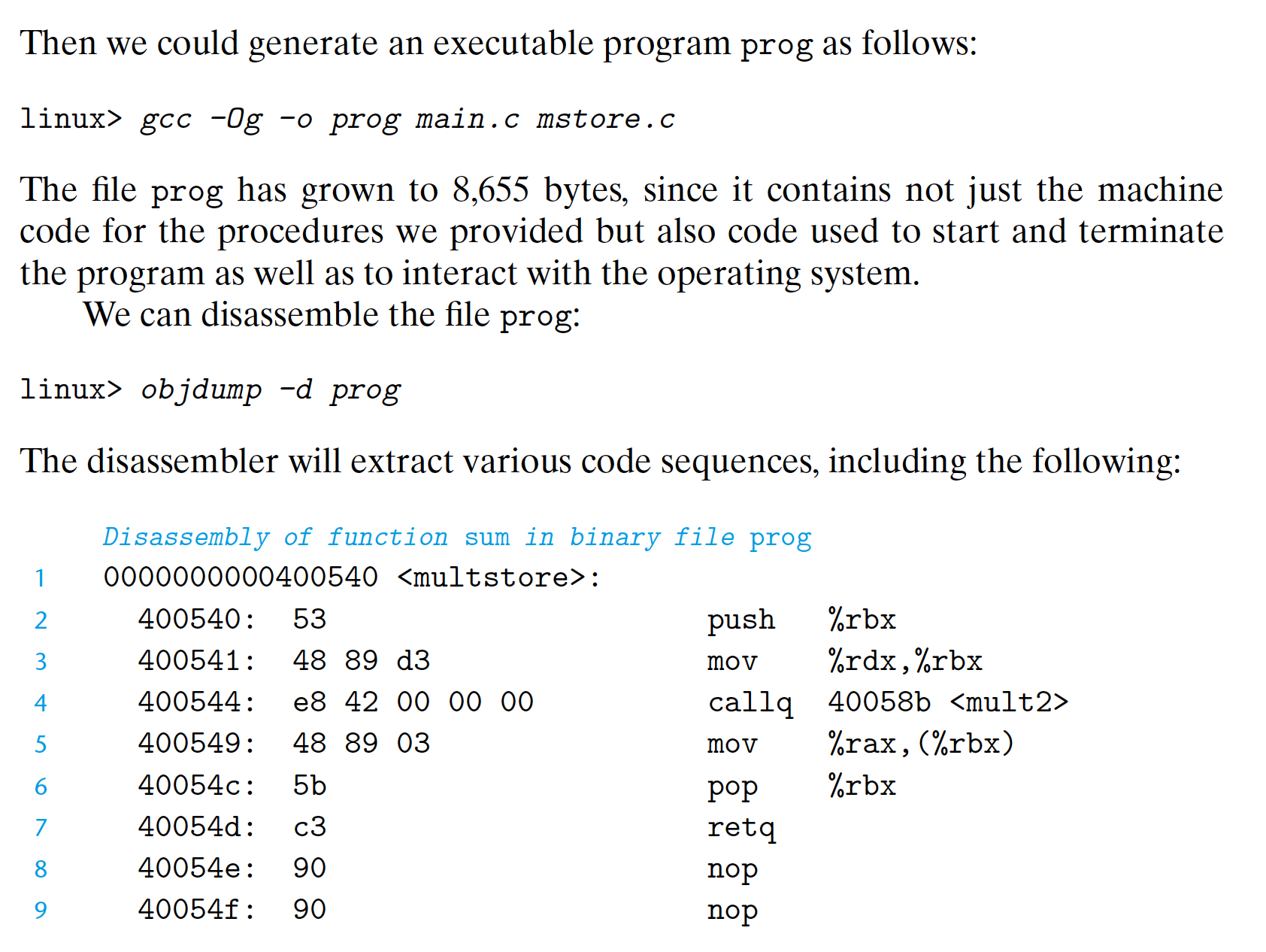

3.7 Procedures

Procedures are a key abstraction in software. They provide a way to package code that implements some functionality with a designated set of arguments and an optional return value. This function can then be invoked from different points in a program.Well-designed software uses procedures as an abstraction mechanism, hiding the detailed implementation of some action while providing a clear and concise interface definition of what values will be computed and what effects the procedure will have on the program state.

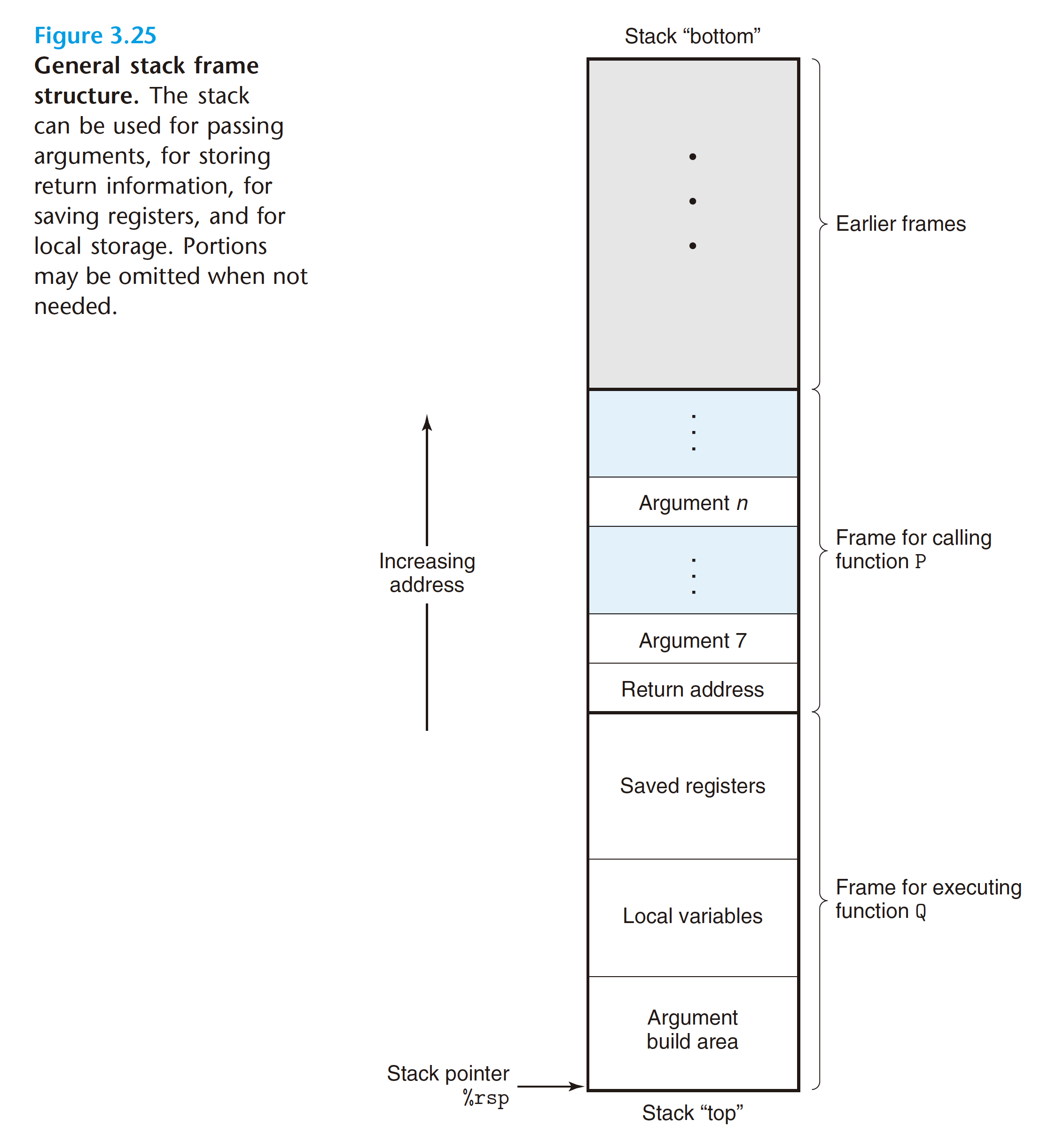

3.7.1 The Run-Time Stack

Using our example of procedure P calling procedure Q, we can see that while Q is executing, P, along with any of the procedures in the chain of calls up to P, is temporarily suspended. While Q is running, only it will need the ability to allocate new storage for its local variables or to set up a call to another procedure. On the other hand, when Q returns, any local storage it has allocated can be freed.

When procedure P calls procedure Q, it will push the return address onto the stack, indicating where within P the program should resume execution once Q returns. We consider the return address to be part of P’s stack frame, since it holds state relevant to P.

When procedure P calls procedure Q, it will push the return address onto the stack, indicating where within P the program should resume execution once Q returns. We consider the return address to be part of P’s stack frame, since it holds state relevant to P.

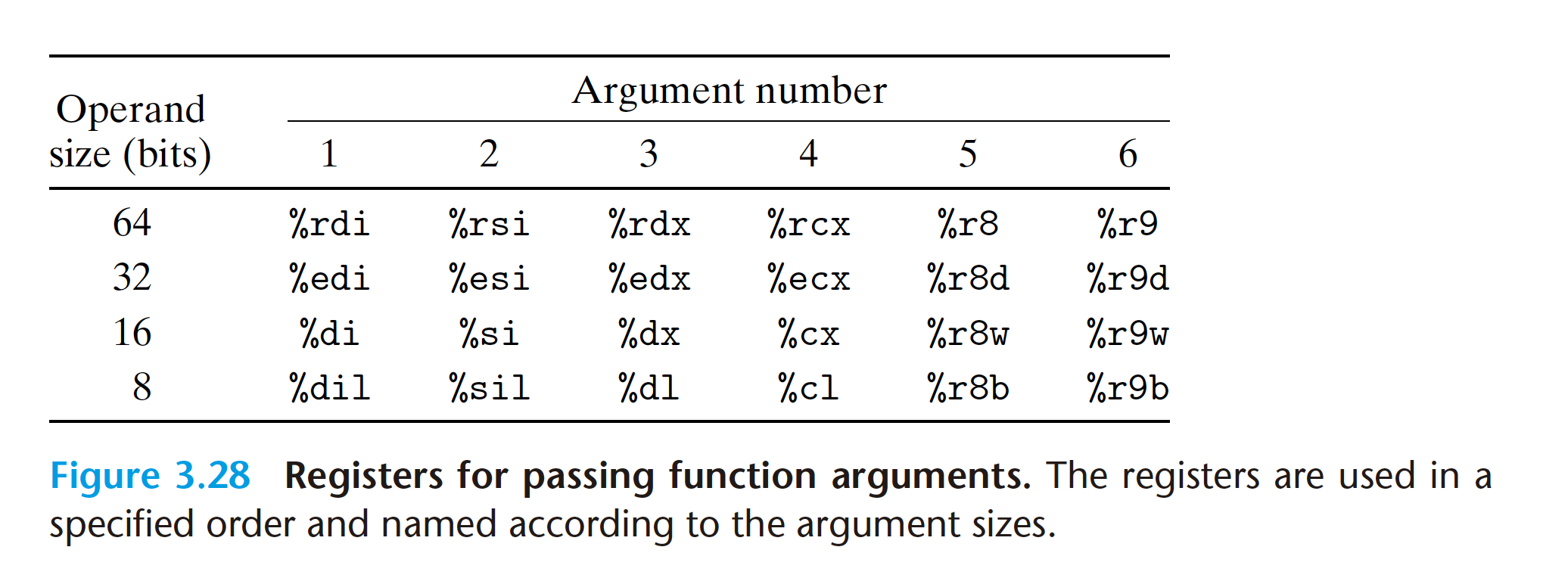

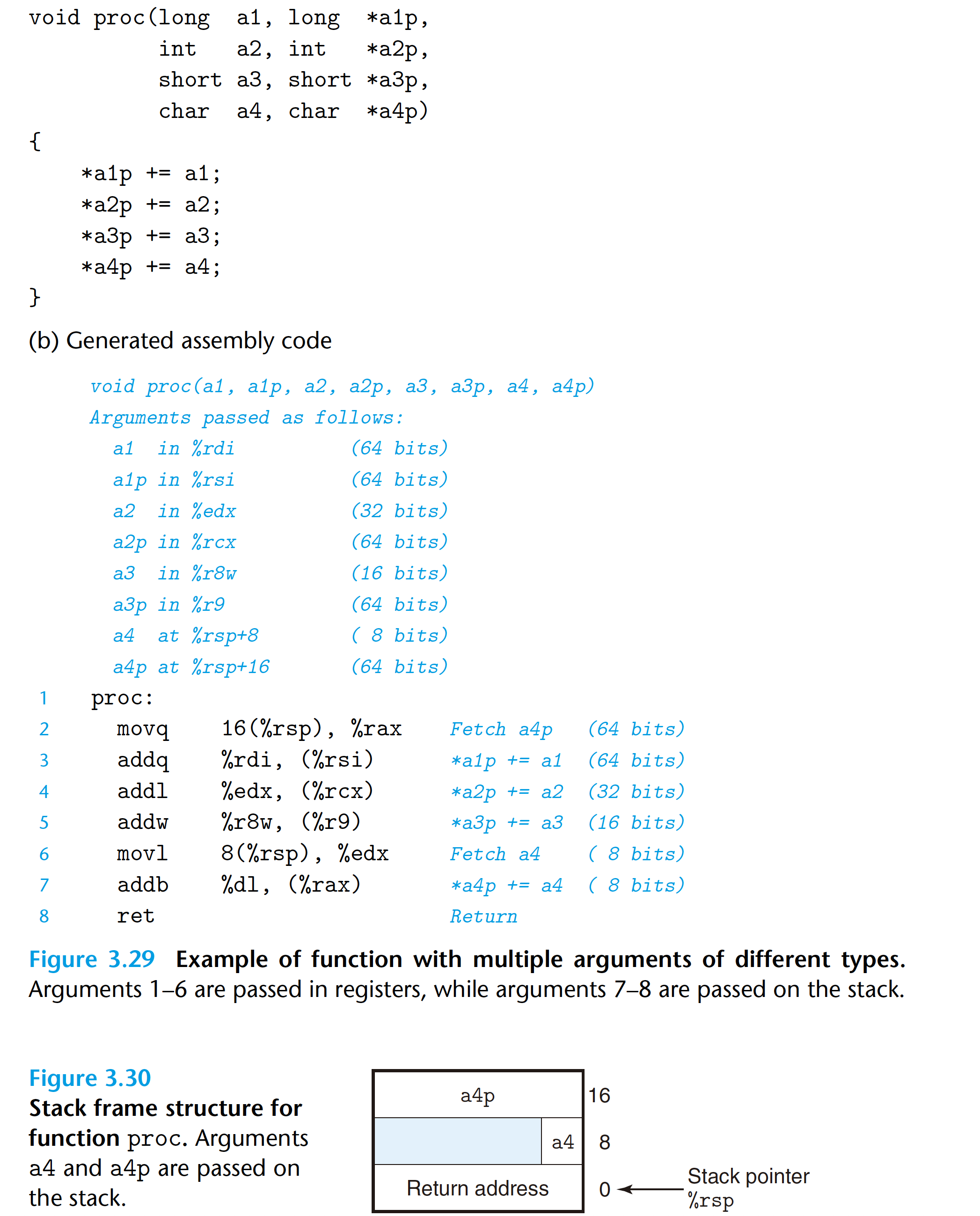

3.7.3 Data transfer

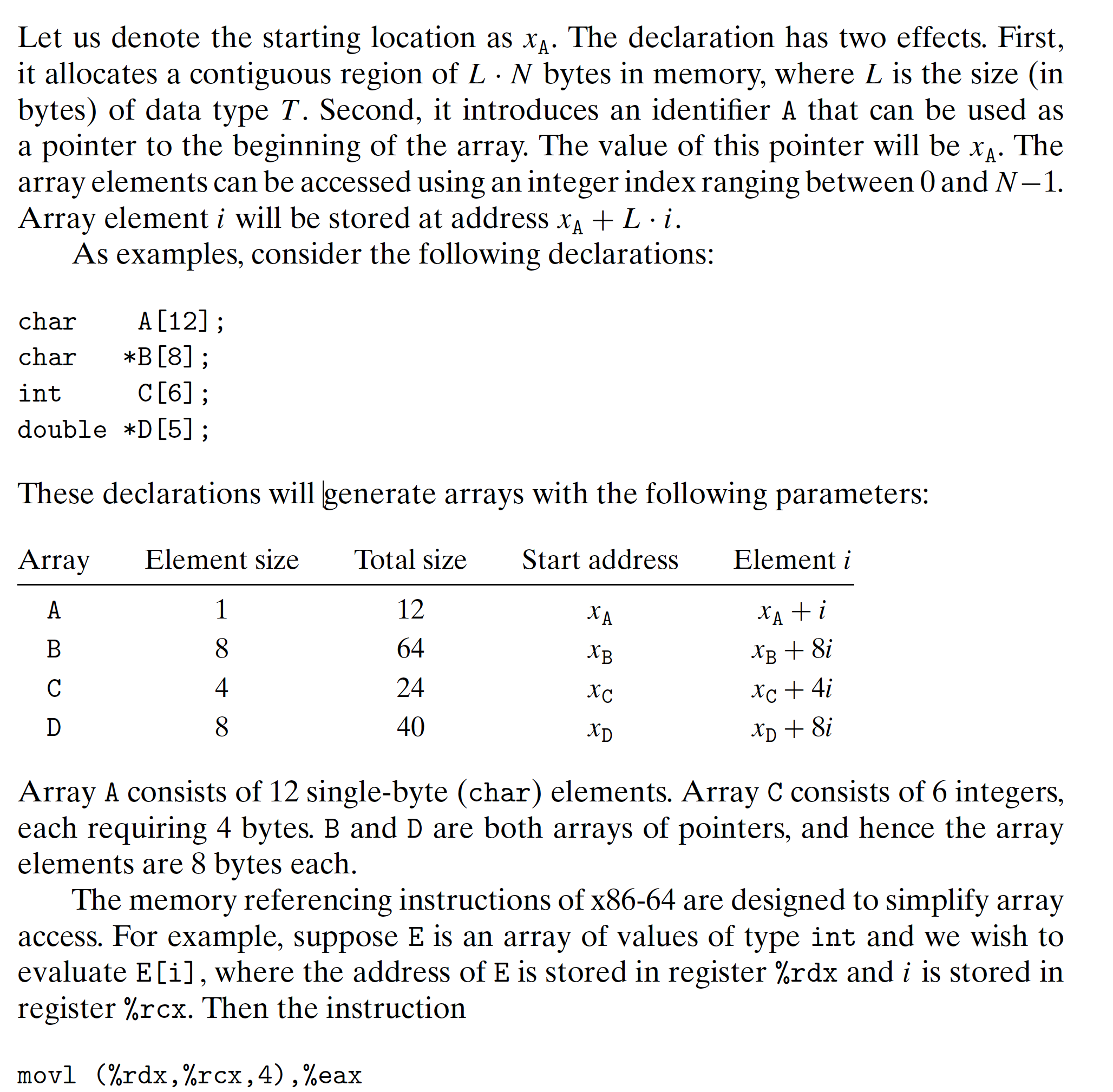

3.8 Array Allocaiton and Access

3.8.1 Basic Principles

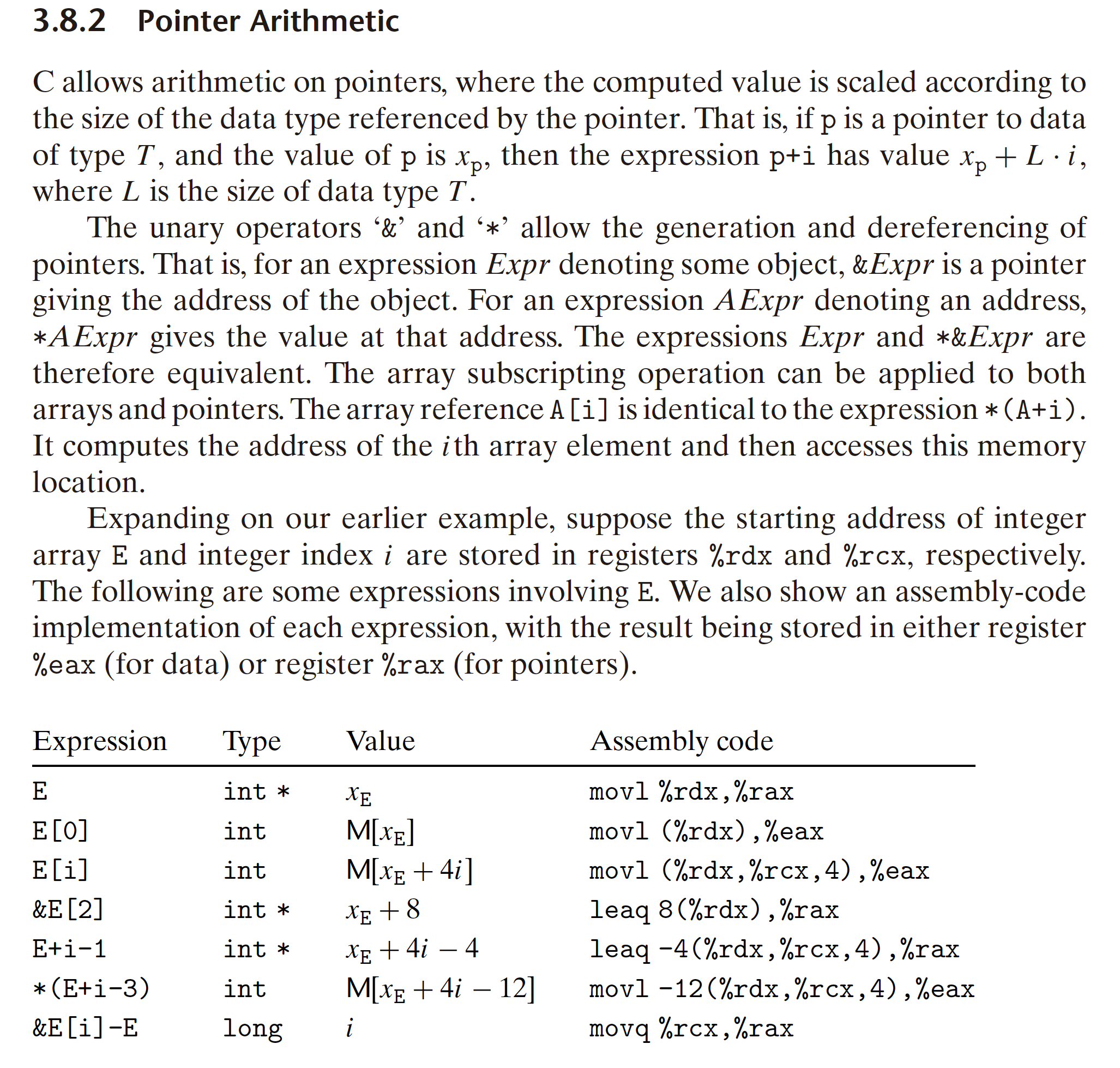

3.8.2 Pointer Arithmetic

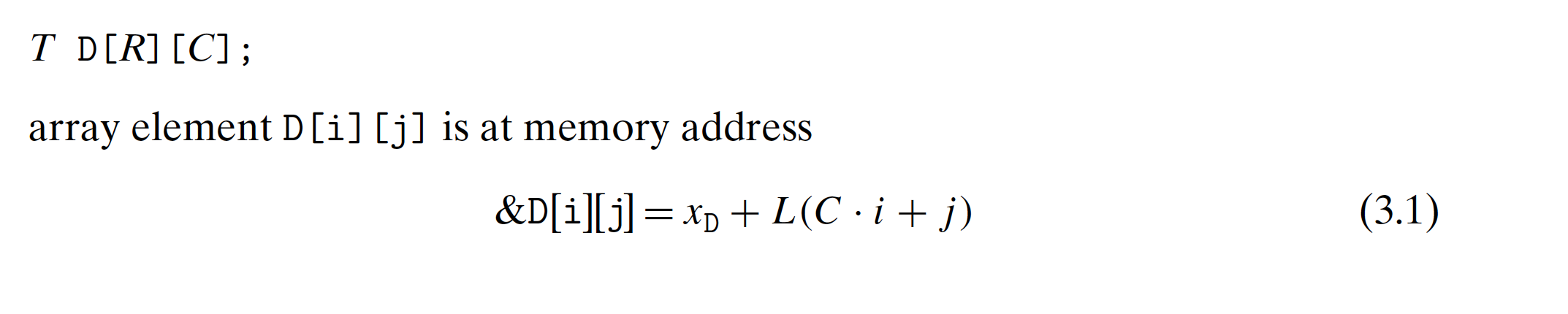

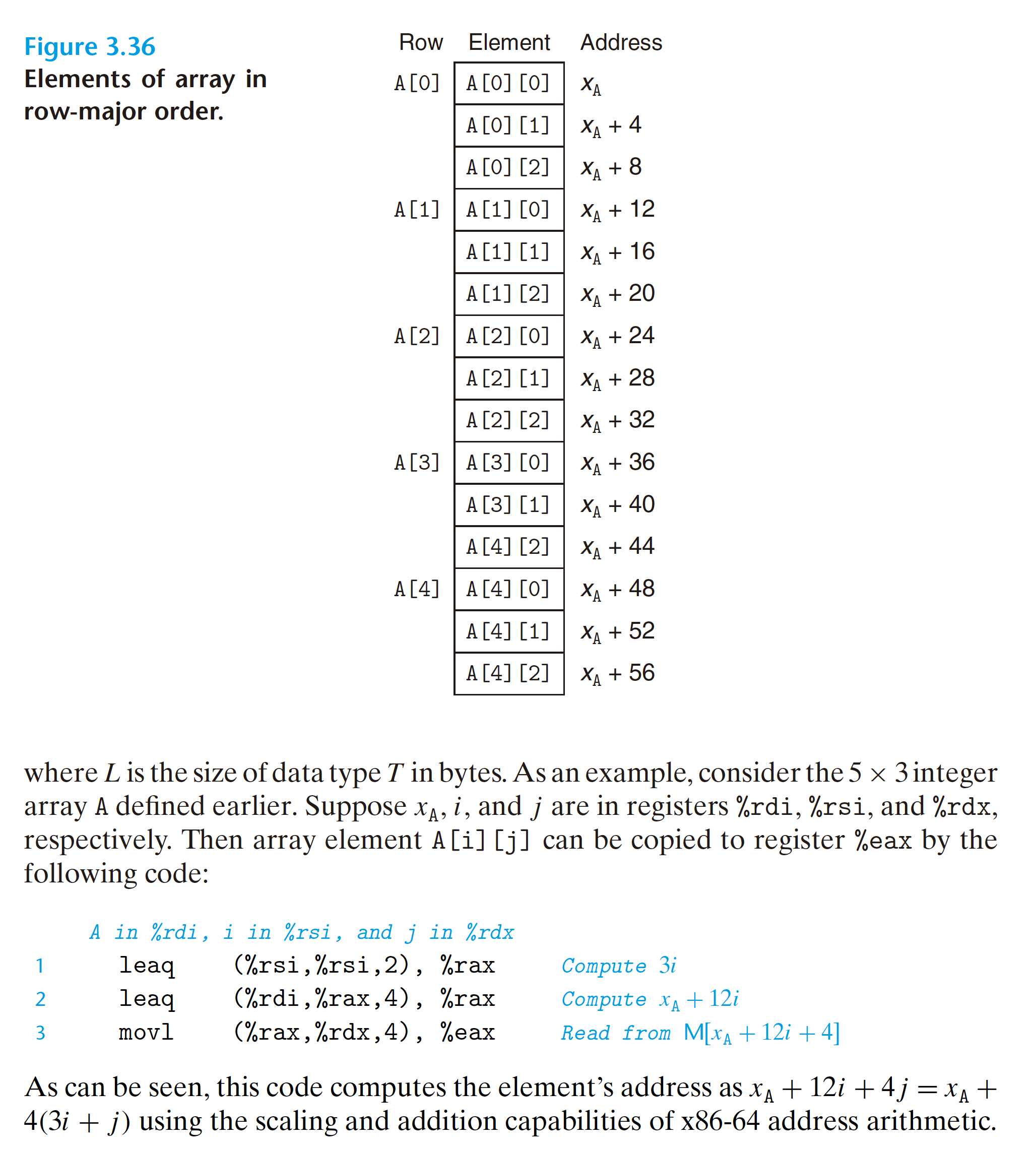

3.8.3 Nested Arrays

3.9 Heterogeneous Data Structures

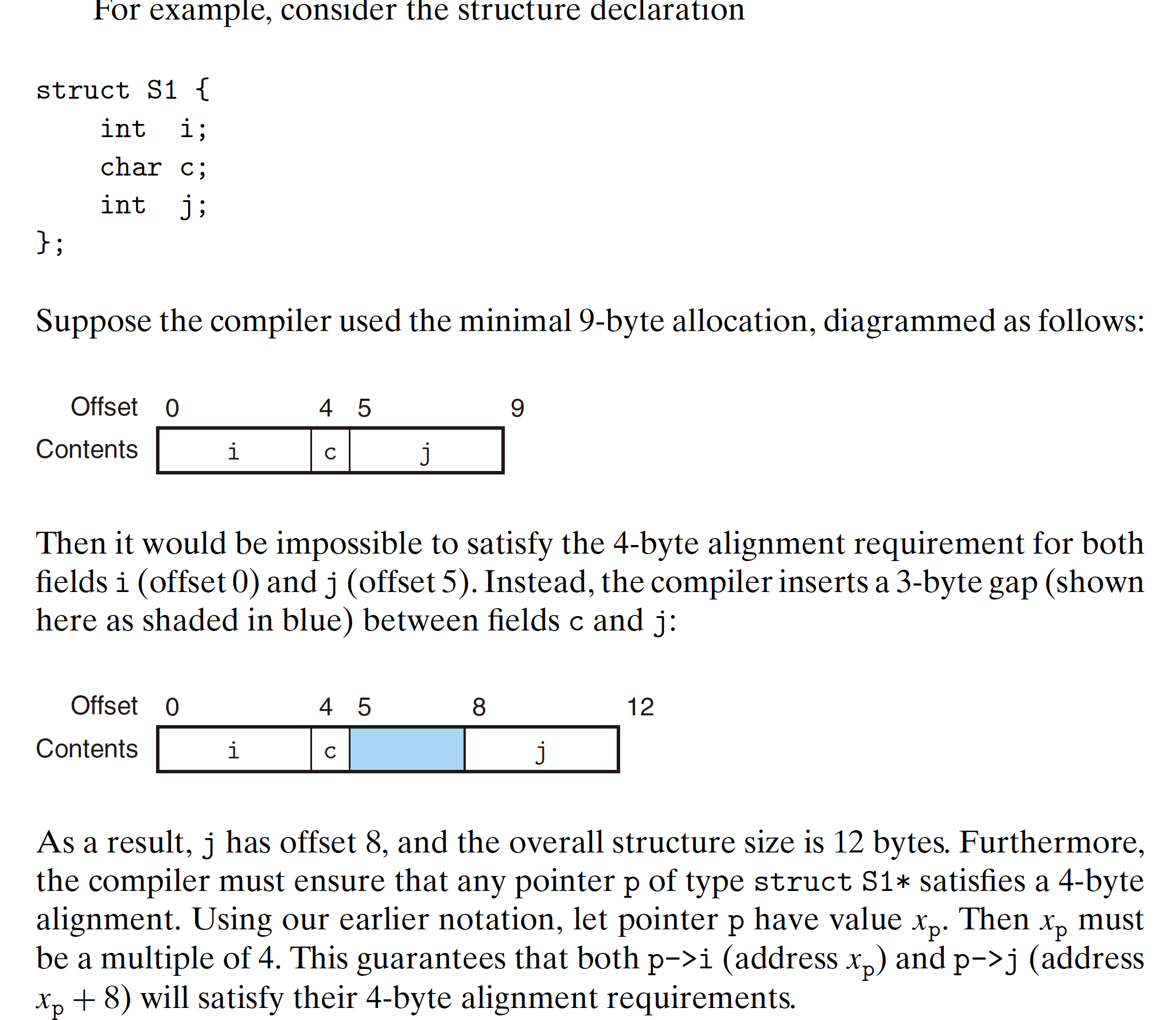

The implementation of structures is similar to that of arrays in that all of the components of a structure are stored in a contiguous region of memory and a pointer to a structure is the address of its first byte. The compiler maintains information about each structure type indicating the byte offset of each field. It generates references to structure elements using these offsets as displacements in memory referencing instructions.

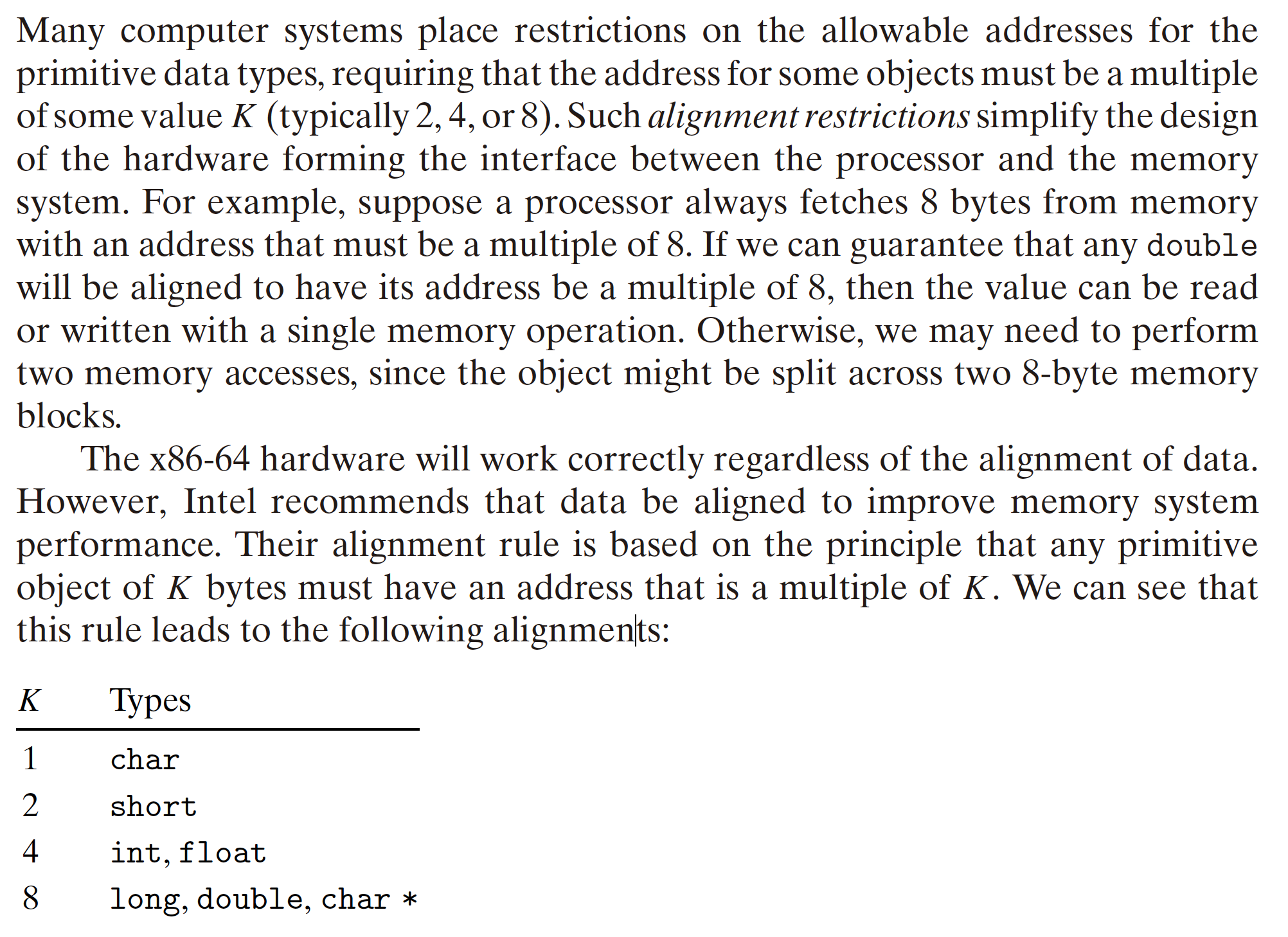

3.9.3 Data Alignment

3.10 combining Control and Data in Machine-Level Programs

3.10.1 Understaning Pointers

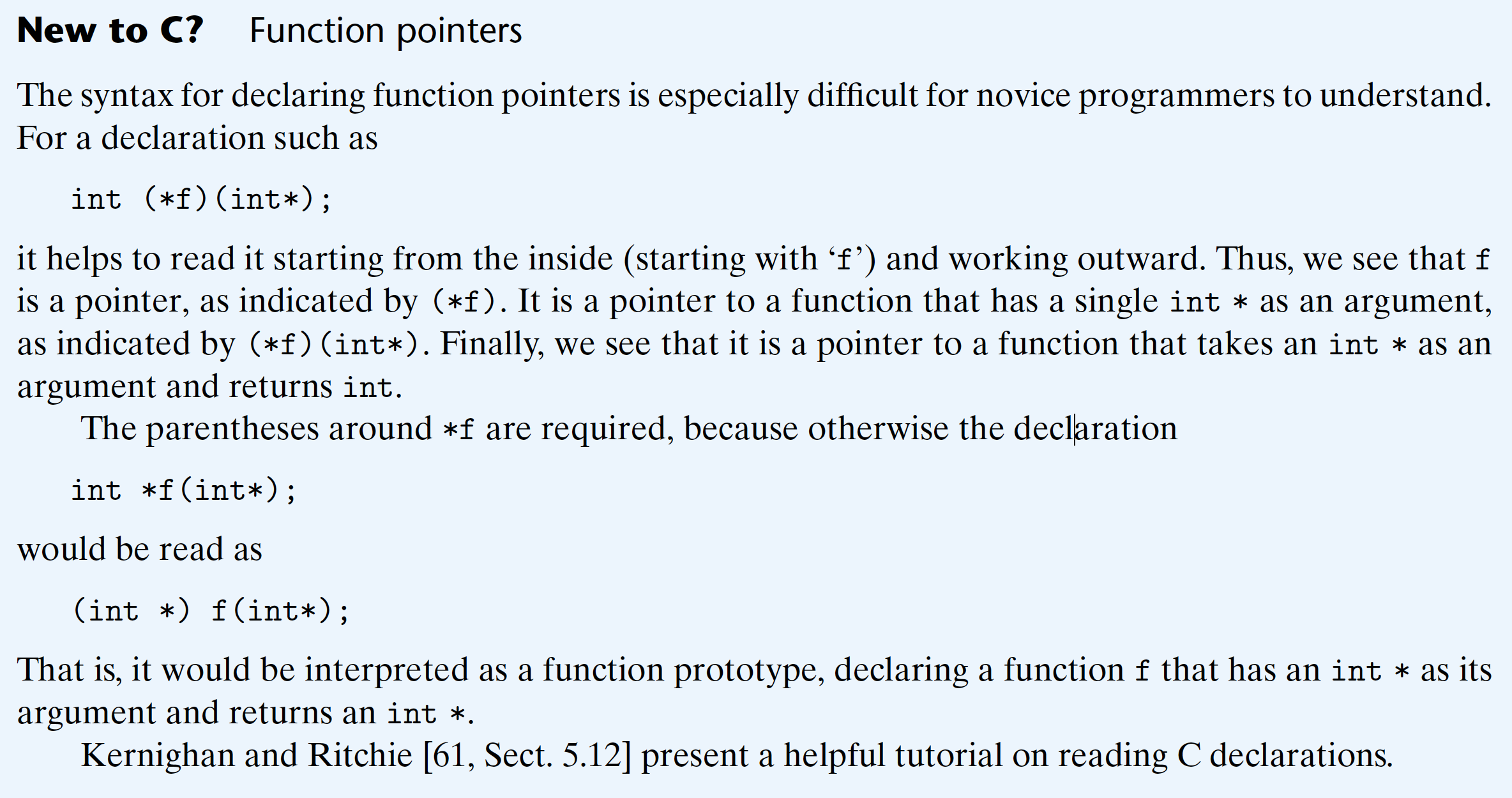

Pointers serve as a uniform way to generate references to elements within different data structures. Here we highlight some key principles of pointers and their mapping into machine code.

- Every pointer has an associated type. This type indicates what kind of object

the pointer points to. Using the following pointer declarations as illustrations

- Every pointer has a value. This value is an address of some object of the designated type. The special NULL (0) value indicates that the pointer does not point anywhere.

- Pointers are created with the ‘&’ operator. This operator can be applied to any

C expression that is categorized as an lvalue, meaning an expression that can

appear on the left side of an assignment. Examples include variables and the

elements of structures, unions, and arrays. We have seen that the machinecode

realization of the ‘&’ operator often uses the

leaqinstruction to compute the expression value, since this instruction is designed to compute the address of a memory reference. - Pointers are dereferenced with the ‘’ operator.* The result is a value having the type associated with the pointer. Dereferencing is implemented by a memory reference, either storing to or retrieving from the specified address.

- Arrays and pointers are closely related. The name of an array can be referenced (but not updated) as if it were a pointer variable. Array referencing (e.g., a[3]) has the exact same effect as pointer arithmetic and dereferencing (e.g., *(a+3)). Both array referencing and pointer arithmetic require scaling the offsets by the object size.When we write an expression p+i for pointer p with value p, the resulting address is computed as p + L . i, where L is the size of the data type associated with p.

- Casting from one type of pointer to another changes its type but not its value. One effect of casting is to change any scaling of pointer arithmetic. So, for

example, if p is a pointer of type

char *having value p, then the expression (int *) p+7 computes p + 28, while (int *) (p+7) computes p + 7. (Recall that casting has higher precedence than addition.) - Pointers can also point to functions. This provides a powerful capability for

storing and passing references to code, which can be invoked in some other

part of the program. For example, if we have a function defined by the proto-type

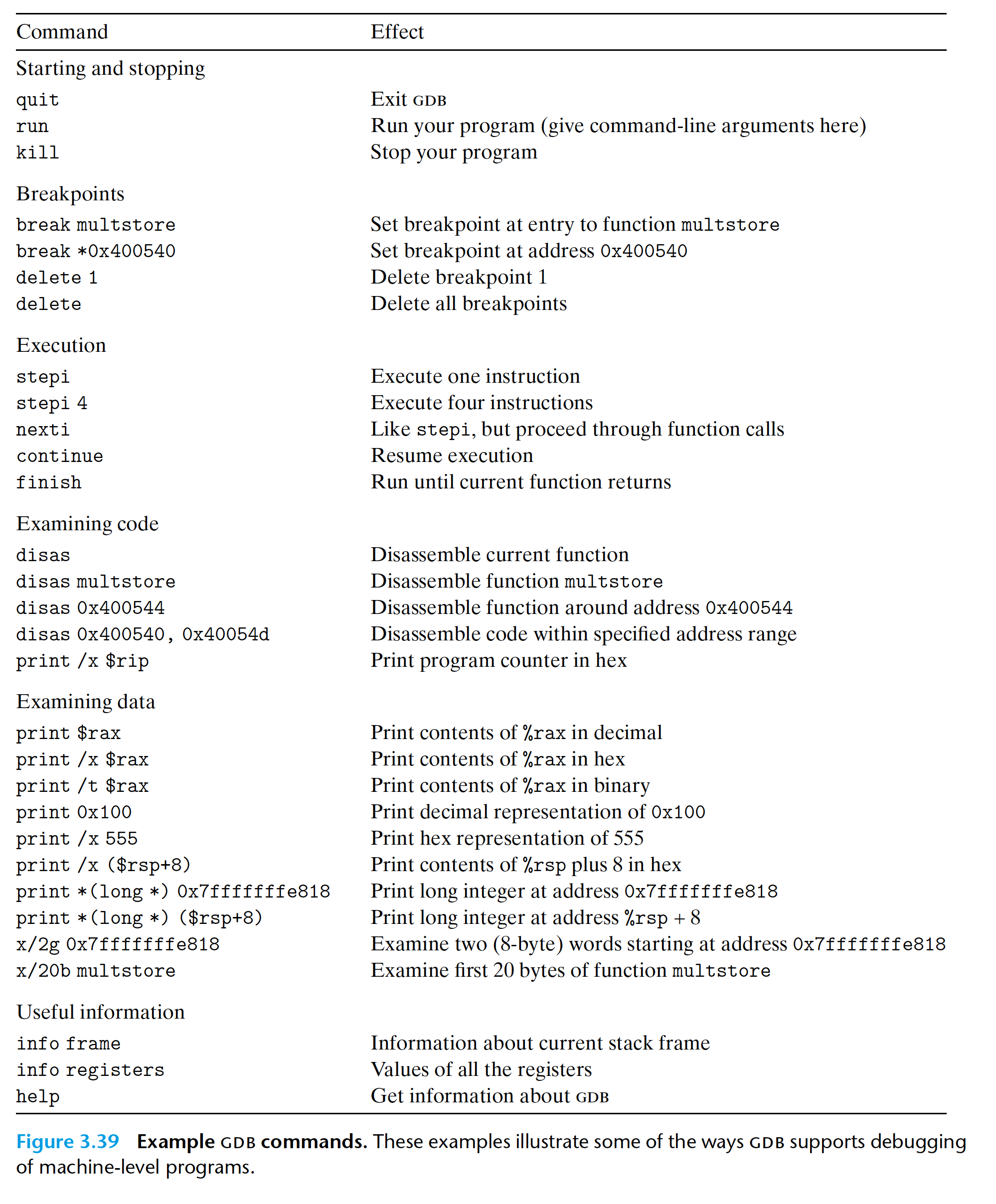

3.10.2 Using the GDB Debugger

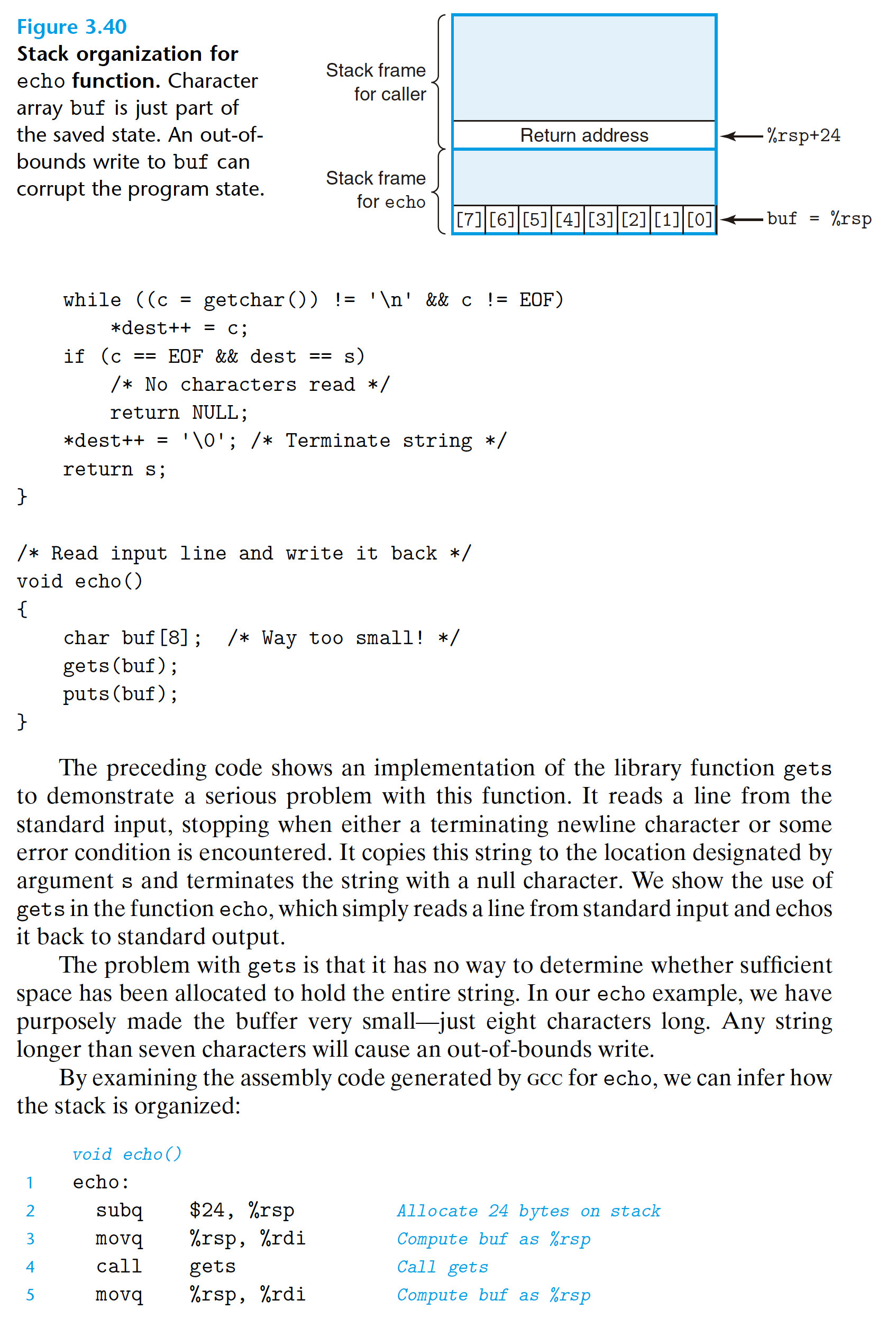

3.10.3 Out-of-Bounds Memory References and Buffer overflow

3.10.4 Thwarting Buffer Overflow Attacks

- Stack Randomization

- Stack Corruption Detection

- Limiting Executable Code Regions

Historically, the x86 architecture merged the read and execute

access controls into a single 1-bit flag, so that any page marked as readable

was also executable. The stack had to be kept both readable and writable, and

therefore the bytes on the stack were also executable. Various schemes were implemented

to be able to limit some pages to being readable but not executable,

but these generally introduced significant inefficiencies.

More recently, AMDintroduced an NX (for “no-execute”) bit into the memory

protection for its 64-bit processors, separating the read and execute access

modes, and Intel followed suit. With this feature, the stack can be marked as being

readable and writable, but not executable, and the checking of whether a page

is executable is performed in hardware, with no penalty in efficiency