Chapter 1: Building Abstractions with Functions

我从CS61A老师那里学到的哲学是

- 多做一些自己没有做过的事

- 不要过分的看重测试和分数,你不必将每一件事都做到完美,但不要停下你前进的脚步,专注于学习、进步和毅力。你很快就能比过去多解决很多问题

- don't compare with others

1.1 Getting Started

1.1.4

Statements & Expressions. Python code consists of expressions and statements. Broadly, computer programs consist of instructions to either

- Compute some value

- Carry out some action

Statements typically describe actions. When the Python interpreter executes a statement, it carries out the corresponding action. On the other hand, expressions typically describe computations. When Python evaluates an expression, it computes the value of that expression.

Functions. Functions encapsulate logic that manipulates data.

Objects. A set is a type of object, one that supports set operations like computing intersections and membership. An object seamlessly bundles together data and the logic that manipulates that data, in a way that manages the complexity of both.

Interpreters. Evaluating compound expressions requires a precise procedure that interprets code in a predictable way. A program that implements such a procedure, evaluating compound expressions, is called an interpreter.

1.2 Elements of Programming

1.2.1 Expressions

1.2.2 Call Expressions

The most important kind of compound expression is a call expression, which applies a function to some arguments.

max(7.5, 9.5) This call expression has subexpressions: the operator is an expression that precedes parentheses, which enclose a comma-delimited list of operand expressions. The operator specifies a function. When this call expression is evaluated(求值), we say that the function max is called with arguments 7.5 and 9.5, and returns a value of 9.5.

1.2.4 Names and the Environment

A critical aspect of a programming language is the means it provides for using names to refer to computational objects. If a value has been given a name, we say that the name binds to the value.

The possibility of binding names to values and later retrieving those values by name means that the interpreter must maintain some sort of memory that keeps track of the names, values, and bindings. This memory is called an environment.

Names can also be bound to functions.

In Python, names are often called variable names or variables because they can be bound to different values in the course of executing a program. When a name is bound to a new value through assignment, it is no longer bound to any previous value. One can even bind built-in names to new values.

- A numeral evaluates to the number it names,

- A name evaluates to the value associated with that name in the current environment.

x=3 does not return a value nor evaluate a function on some arguments, since the purpose of assignment is instead to bind a name to a value. In general, statements are not evaluated but executed; they do not produce a value but instead make some change. Each type of expression or statement has its own evaluation or execution procedure.

1.2.6 The Non-Pure Print Function

- Pure functions. Functions have some input (their arguments) and return some output (the result of applying them). The built-in function

- Non-pure functions. In addition to returning a value, applying a non-pure function can generate side effects, which make some change to the state of the interpreter or computer. A common side effect is to generate additional output beyond the return value, using the print function.

1.3 Defining New Functions

How to define a function. Function definitions consist of a def statement that indicates a <name> and a comma-separated list of named <formal parameters>, then a return statement, called the function body, that specifies the <return expression> of the function, which is an expression to be evaluated whenever the function is applied:

1.3.1 Environments

An environment in which an expression is evaluated consists of a sequence of frames, depicted as boxes. Each frame contains bindings, each of which associates a name with its corresponding value.

An import statement binds a name to a built-in function. A def statement binds a name to a user-defined function created by the definition.

Each function is a line that starts with func, followed by the function name and formal parameters. Built-in functions such as mul do not have formal parameter names, and so ... is always used instead.

The name of a function is repeated twice, once in the frame and again as part of the function itself. The name appearing in the function is called the intrinsic name. The name in a frame is a bound name. There is a difference between the two: different names may refer to the same function, but that function itself has only one intrinsic name.

The name bound to a function in a frame is the one used during evaluation. The intrinsic name of a function does not play a role in evaluation.

Function Signatures. A description of the formal parameters of a function is called the function's signature.

1.3.2 Calling User-Defined Functions

Applying a user-defined function introduces a second local frame, which is only accessible to that function. To apply a user-defined function to some arguments:

- Bind the arguments to the names of the function's formal parameters in a new local frame.

- Execute the body of the function in the environment that starts with this frame.

The environment in which the body is evaluated consists of two frames: first the local frame that contains formal parameter bindings, then the global frame that contains everything else. Each instance of a function application has its own independent local frame.

Name Evaluation. A name evaluates to the value bound to that name in the earliest frame of the current environment in which that name is found.

Aspects of a functional abstraction. To master the use of a functional abstraction, it is often useful to consider its three core attributes. The domain of a function is the set of arguments it can take. The range of a function is the set of values it can return. The intent of a function is the relationship it computes between inputs and output (as well as any side effects it might generate). Understanding functional abstractions via their domain, range, and intent is critical to using them correctly in a complex program.

1.4 Designing Functions

Fundamentally, the qualities of good functions all reinforce the idea that functions are abstractions.

- Each function should have exactly one job. That job should be identifiable with a short name and characterizable in a single line of text. Functions that perform multiple jobs in sequence should be divided into multiple functions.

- Don't repeat yourself is a central tenet of software engineering. The so-called DRY principle states that multiple fragments of code should not describe redundant logic. Instead, that logic should be implemented once, given a name, and applied multiple times. If you find yourself copying and pasting a block of code, you have probably found an opportunity for functional abstraction.

- Functions should be defined generally. Squaring is not in the Python Library precisely because it is a special case of the pow function, which raises numbers to arbitrary powers.

1.5 Control

1.5.2 Compound Statements

A compound statement is so called because it is composed of other statements (simple and compound). Compound statements typically span multiple lines and start with a one-line header ending in a colon, which identifies the type of statement. Together, a header and an indented suite of statements is called a clause. A compound statement consists of one or more clauses:

Expressions can also be executed as statements, in which case they are evaluated, but their value is discarded.We can understand the statements we have already introduced in these terms.

- Expressions, return statements, and assignment statements are simple statements.

- A

defstatement is a compound statement. The suite that follows the def header defines the function body.

Specialized evaluation rules for each kind of header dictate when and if the statements in its suite are executed. We say that the header controls its suite. For example, in the case of def statements, we saw that the return expression is not evaluated immediately, but instead stored for later use when the defined function is eventually called.

We can also understand multi-line programs now.

- To execute a sequence of statements, execute the first statement. If that statement does not redirect control, then proceed to execute the rest of the sequence of statements, if any remain.

This definition exposes the essential structure of a recursively defined sequence: a sequence can be decomposed into its first element and the rest of its elements. The "rest" of a sequence of statements is itself a sequence of statements! Thus, we can recursively apply this execution rule. This view of sequences as recursive data structures will appear again in later chapters.

The important consequence of this rule is that statements are executed in order, but later statements may never be reached, because of redirected control.

1.5.3 Defining Functions II: Local Assignment

A return statement redirects control: the process of function application terminates whenever the first return statement is executed, and the value of the return expression is the returned value of the function being applied.

The effect of an assignment statement is to bind a name to a value in the first frame of the current environment.

Boolean contexts. Python includes several false values, including 0, None, and the boolean value False. All other numbers are true values. every built-in kind of data in Python has both true and false values.

1.6 Higher-Order Functions

Functions that manipulate functions are called higher-order functions.

1.6.1 Functions as Arguments

1.6.2 Functions as General Methods

1.6.3 Defining Functions III: Nested Definitions

The above examples demonstrate how the ability to pass functions as arguments significantly enhances the expressive power of our programming language. Each general concept or equation maps onto its own short function. One negative consequence of this approach is that the global frame becomes cluttered with names of small functions, which must all be unique. Another problem is that we are constrained by particular function signatures: the update argument to improve must take exactly one argument. Nested function definitions address both of these problems, but require us to enrich our environment model.

>>> def sqrt(a):

def sqrt_update(x):

return average(x, a/x)

def sqrt_close(x):

return approx_eq(x * x, a)

return improve(sqrt_update, sqrt_close)

def statements only affect the current local frame. These functions are only in scope while sqrt is being evaluated. Consistent with our evaluation procedure, these local def statements don't even get evaluated until sqrt is called.

Lexical scope. Locally defined functions also have access to the name bindings in the scope in which they are defined. In this example, sqrt_update refers to the name a, which is a formal parameter of its enclosing function sqrt. This discipline of sharing names among nested definitions is called lexical scoping. Critically, the inner functions have access to the names in the environment where they are defined (not where they are called).

We require two extensions to our environment model to enable lexical scoping.

- Each user-defined function has a parent environment: the environment in which it was defined

- When a user-defined function is called, its local frame extends its parent environment.

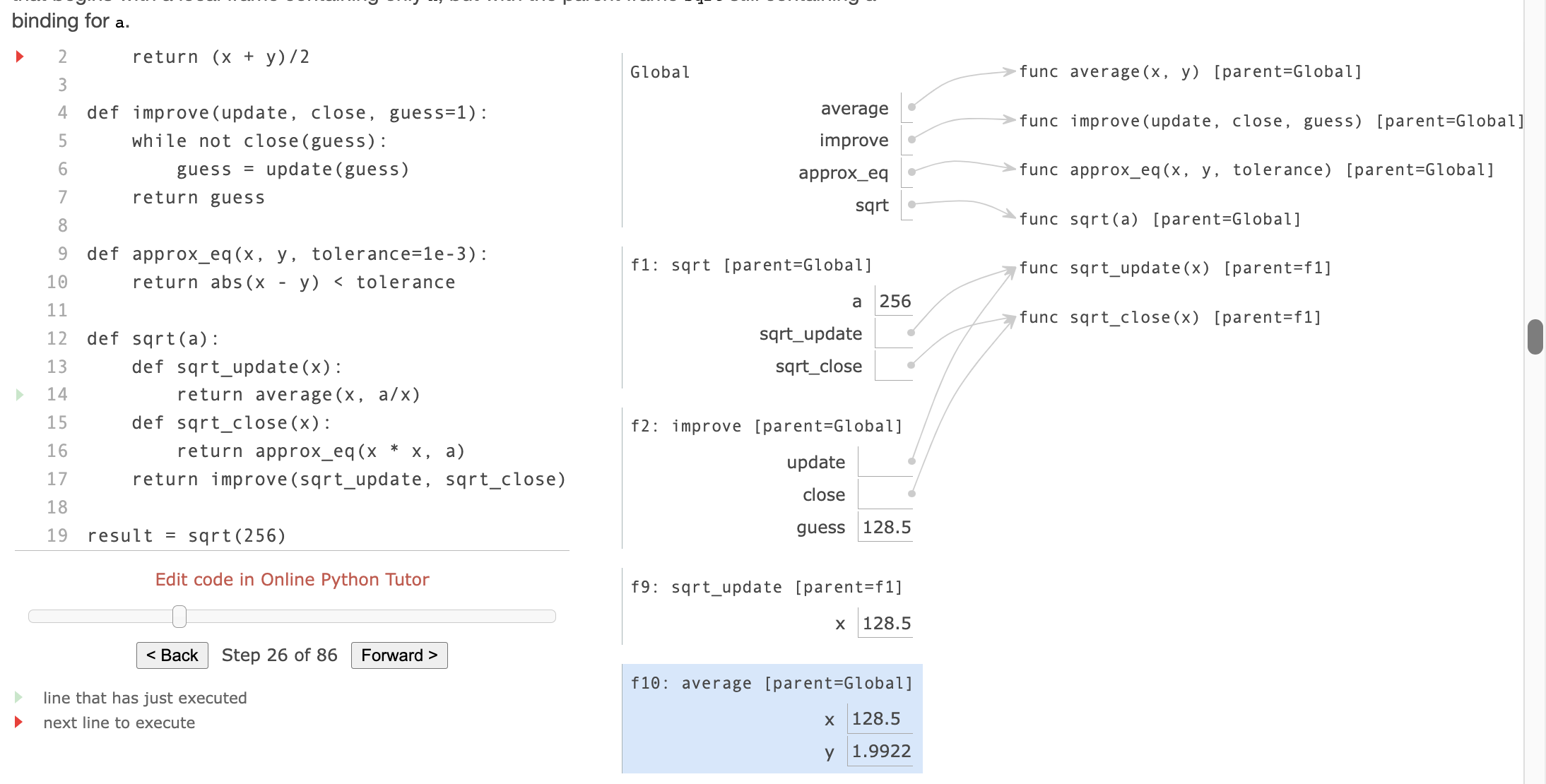

1 def average(x, y):

2 return (x + y)/2

3

4 def improve(update, close, guess=1):

5 while not close(guess):

6 guess = update(guess)

7 return guess

8

9 def approx_eq(x, y, tolerance=1e-3):

10 return abs(x - y) < tolerance

11

12 def sqrt(a):

13 def sqrt_update(x):

14 return average(x, a/x)

15 def sqrt_close(x):

16 return approx_eq(x * x, a)

17 return improve(sqrt_update, sqrt_close)

18

19 result = sqrt(256)

Extended Environments. An environment can consist of an arbitrarily long chain of frames, which always concludes with the global frame. Previous to this

Extended Environments. An environment can consist of an arbitrarily long chain of frames, which always concludes with the global frame. Previous to this sqrt example, environments had at most two frames: a local frame and the global frame. By calling functions that were defined within other functions, via nested def statements, we can create longer chains. The environment for this call to sqrt_update consists of three frames: the local sqrt_update frame, the sqrt frame in which sqrt_update was defined (labeled f1), and the global frame.

The return expression in the body of sqrt_update can resolve a value for a by following this chain of frames. Looking up a name finds the first value bound to that name in the current environment. Python checks first in the sqrt_update frame -- no a exists. Python checks next in the parent frame, f1, and finds a binding for a to 256.

Hence, we realize two key advantages of lexical scoping in Python.

- The names of a local function do not interfere with names external to the function in which it is defined, because the local function name will be bound in the current local environment in which it was defined, rather than the global environment.

- A local function can access the environment of the enclosing function, because the body of the local function is evaluated in an environment that extends the evaluation environment in which it was defined.

Thesqrt_updatefunction carries with it some data: the value forareferenced in the environment in which it was defined. Because they "enclose" information in this way, locally defined functions are often called closures.

1.6.4 Functions as Returned Values

We can achieve even more expressive power in our programs by creating functions whose returned values are themselves functions. An important feature of lexically scoped programming languages is that locally defined functions maintain their parent environment when they are returned.

1.6.5 Example: Newton's Method

This extended example shows how function return values and local definitions can work together to express general ideas concisely.

>>> def find_zero(f, df):

def near_zero(x):

return approx_eq(f(x), 0)

return improve(newton_update(f, df), near_zero)

1.6.6 Currying

We can use higher-order functions to convert a function that takes multiple arguments into a chain of functions that each take a single argument. More specifically, given a function f(x, y), we can define a function g such that g(x)(y) is equivalent to f(x, y).

>>> def curry2(f):

"""Return a curried version of the given two-argument function."""

def g(x):

def h(y):

return f(x, y)

return h

return g

>>> def uncurry2(g):

"""Return a two-argument version of the given curried function."""

def f(x, y):

return g(x)(y)

return f

1.6.7 Lambda Expressions

lambda |

x |

: |

f(g(x)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| a function that | takes x | and returns | f(g(x)) |

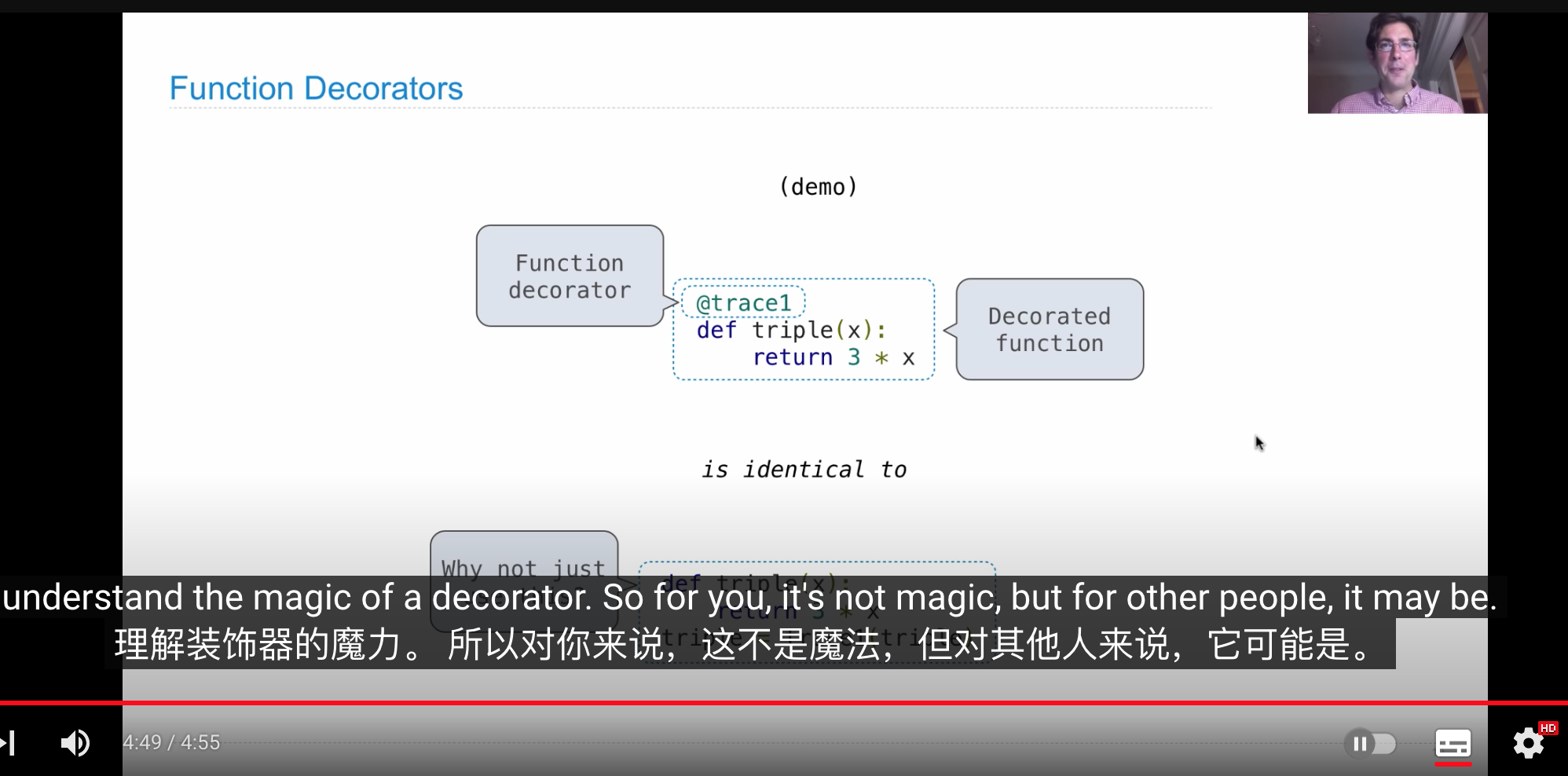

1.6.9 Function Decorators

>>> def trace(fn):

def wrapped(x):

print('-> ', fn, '(', x, ')')

return fn(x)

return wrapped

>>> @trace

def triple(x):

return 3 * x

>>> triple(12)

-> <function triple at 0x102a39848> ( 12 )

36

def statement for triple has an annotation, @trace, which affects the execution rule for def. As usual, the function triple is created. However, the name triple is not bound to this function. Instead, the name triple is bound to the returned function value of calling trace on the newly defined triple function. In code, this decorator is equivalent to:

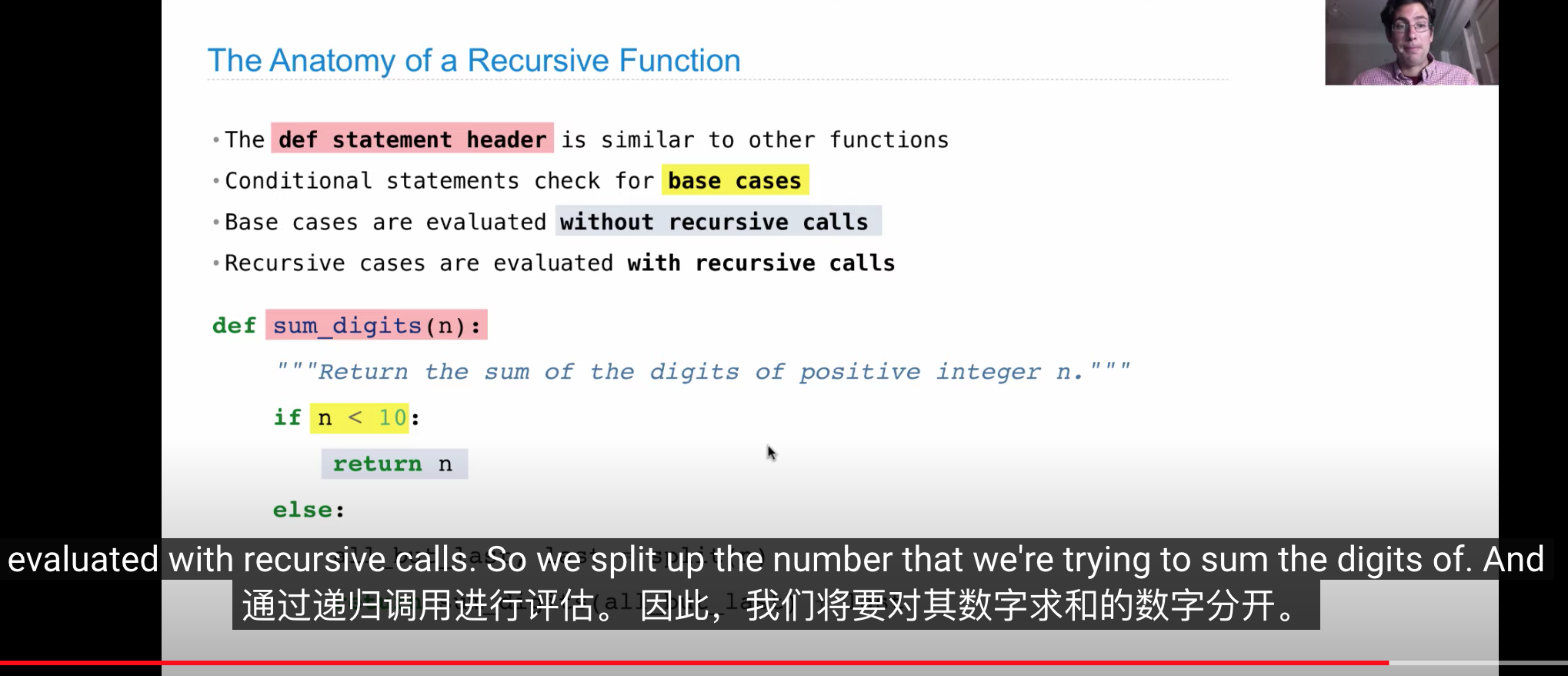

1.7 Recursive Functions

A function is called recursive if the body of the function calls the function itself, either directly or indirectly. That is, the process of executing the body of a recursive function may in turn require applying that function again.

1.7.1 The Anatomy of Recursive Functions

1.7.2 Mutual Recursion

When a recursive procedure is divided among two functions that call each other, the functions are said to be mutually recursive.

Using this definition, we can implement mutually recursive functions to determine whether a number is even or odd:

1 def is_even(n):

2 if n == 0:

3 return True

4 else:

5 return is_odd(n-1)

6

7 def is_odd(n):

8 if n == 0:

9 return False

10 else:

11 return is_even(n-1)

12

13 result = is_even(4)

1.7.3 Printing in Recursive Functions

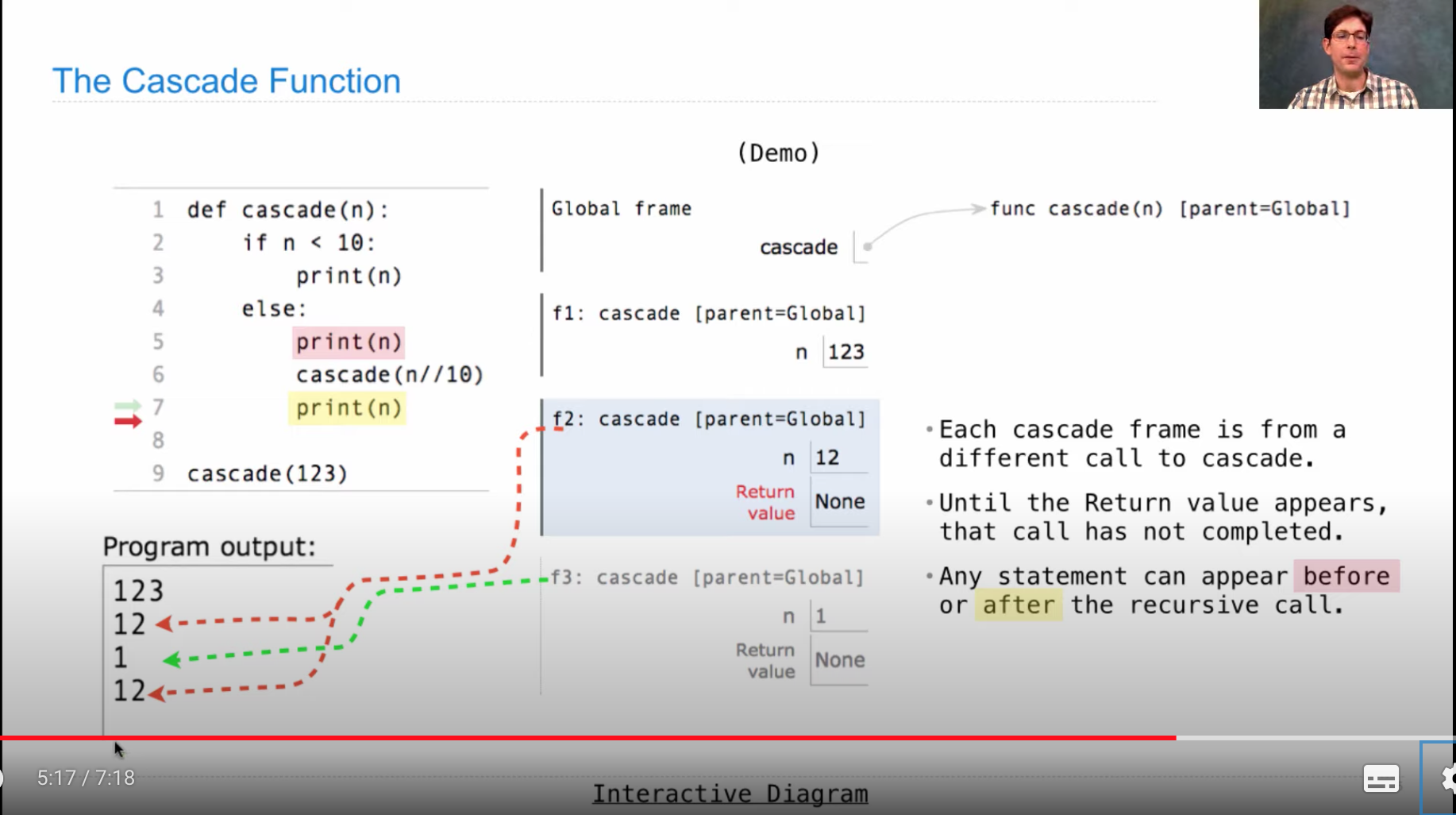

>>> def cascade(n):

"""Print a cascade of prefixes of n."""

if n < 10:

print(n)

else:

print(n)

cascade(n//10)

print(n)

>>> cascade(2013)

2013

201

20

2

20

201

2013